Rights, Commerce, and Reform

The end of Reconstruction and the start of Industrialization led to a 50-year era where the Supreme Court addressed constitutional questions about rights, commerce, and reform.

Illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House.

Illustration shows a “Standard Oil” storage tank as an octopus with many tentacles wrapped around the steel, copper, and shipping industries, as well as a state house, the U.S. Capitol, and one tentacle reaching for the White House.

Background

The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked a significant turning point for the United States. Though the fighting ended, major racial, regional, and political conflicts persisted. The federal government addressed these problems over the next 12 years. During this time, known as Reconstruction, the states ratified three new constitutional amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth—that created constitutional protections for African Americans. Reconstruction ended after the Election of 1876, when the majority-Republican Congress agreed to demilitarize the South. The former Confederate states, which were dominated by the Democratic party, had been under martial law since 1867. In return, both sides agreed to recognize Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as the winner of the closely decided and disputed 1876 election.

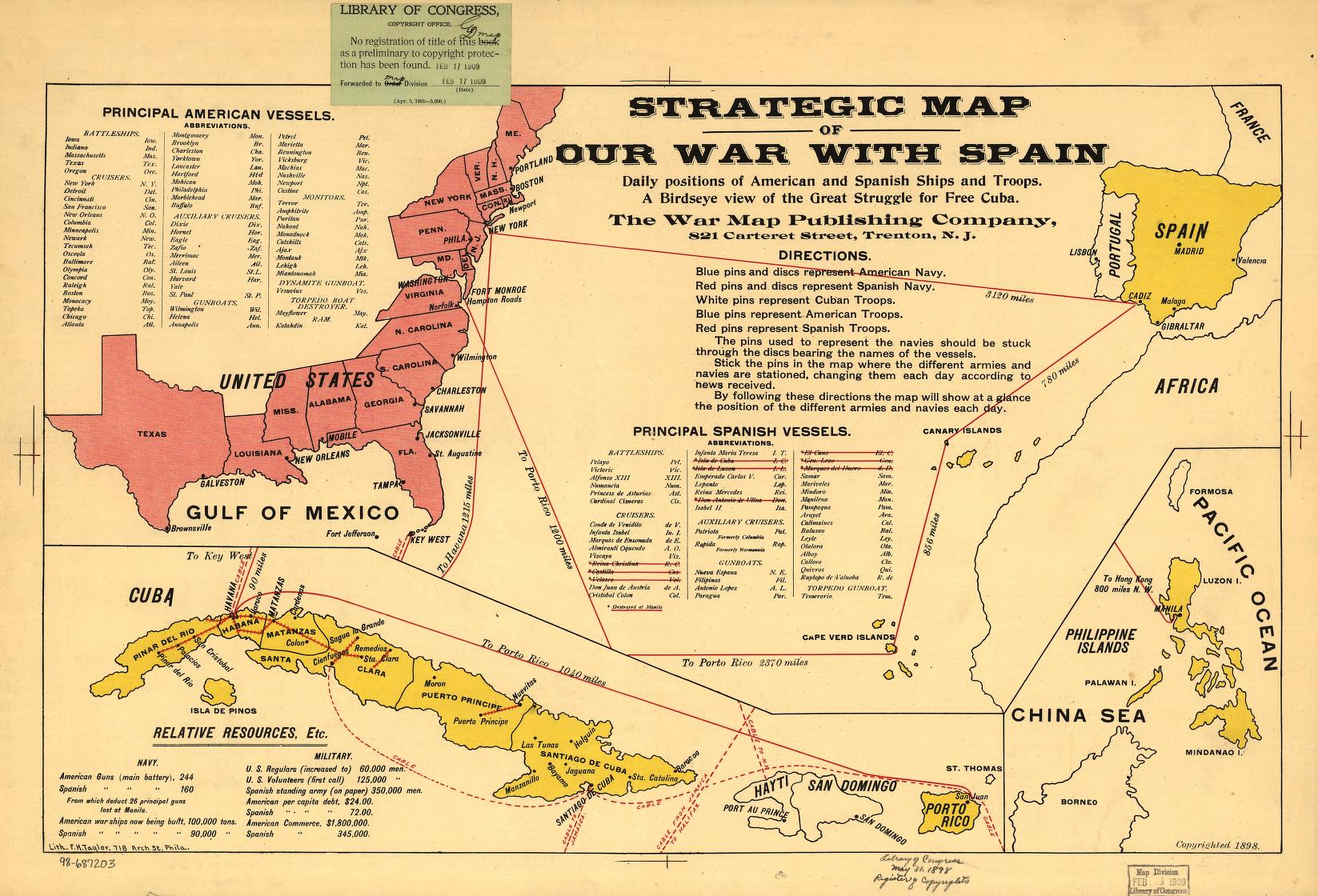

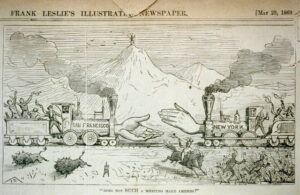

At the same time, the Gilded Age began as rapid industrialization generated unprecedented economic growth. Before 1880, over half of the country’s population worked on farms. Between 1860 and 1920, however, the urban population ballooned from 6.2 million to 54.2 million people. Rural migrants and over 12 million immigrants flocked to cities hoping to secure a job in one of the many new factories. Additionally, railroad lines multiplied by nearly six times, growing from 35,000 miles pre-Civil War to over 200,000 miles by 1899. Expanding railroad routes, especially the transcontinental railroad, connected the nation and facilitated the exchange of people, goods, and ideas. Opening these territories to American settlers, however, violated treaties with Native American tribes and threatened their sovereignty.

Between 1874 and 1921, post-Civil War and industrial problems intersected—Reconstruction ended, the Jim Crow era began, the country acquired new territories, and some of the nation’s largest-ever companies rose and fell. The racial conflicts, industrial working conditions, and commercial disputes that occurred during this time presented distinct problems. They centered, however, on the powers of the federal and state governments to protect the interests of individuals and, later, businesses. As these issues manifested themselves as legal challenges, the Supreme Court of the United States interpreted and applied the new Reconstruction Amendments, especially the Fourteenth Amendment, as it considered constitutional questions about rights, commerce, and reform.

Rights

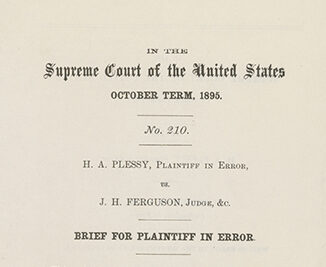

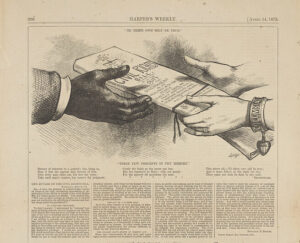

The Supreme Court issued one of the first interpretations of the Fourteenth Amendment in Cruikshank v. United States (1875). The case challenged the convictions of several Ku Klux Klan mob members who killed as many as 160 Black voters following a local election in Louisiana. The Supreme Court unanimously overturned their convictions. According to Cruikshank, the Fourteenth Amendment’s rights of due process and equal protection only applied to state actions, not the actions of individuals. The Court applied similar reasoning when it struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The act, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations (like restaurants and theatres) had no constitutional basis since only the states—not private businesses or individuals—needed to uphold the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court cited the Civil Rights Cases (1883) as precedent in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which legalized racial segregation.

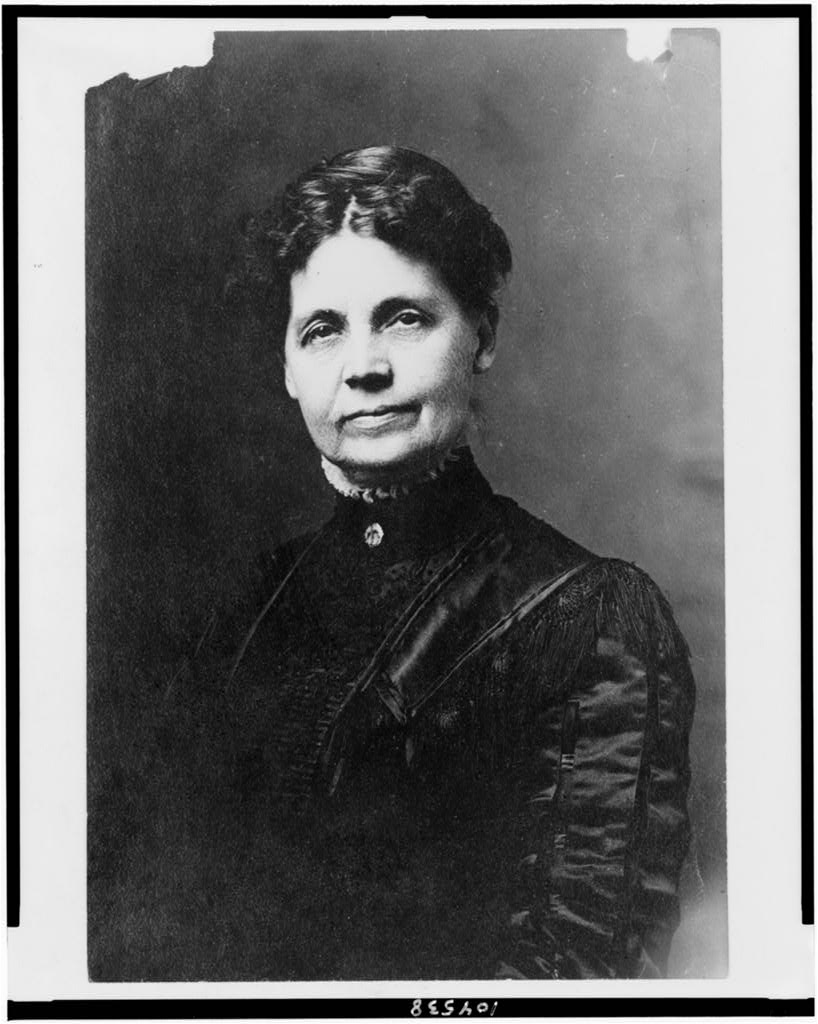

The Court also considered how the Fourteenth Amendment applied to other marginalized groups. Lawyer Myra Bradwell, for example, sued the state of Illinois for denying her admission to its bar because she was a woman. The Court upheld the state’s right to deny Bradwell a law license in Bradwell v. Illinois (1873). The decision did not stop women from participating in law, however, and around the same time, Belva Lockwood successfully lobbied Congress to pass a bill banning discrimination against female attorneys. She became the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court in 1880. Additionally, an influx of immigration during the Industrial Revolution generated questions about citizenship. The 1898 decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark affirmed that birthright citizenship is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Meanwhile, settlers increasingly moved into western territories, raising questions about the self-governing powers of Native American tribes. By 1903, the Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock decision held that Congress had full legal authority to control tribes through acts of Congress and could disregard any established treaties. In the Insular Cases, heard from 1901 to 1904, the Supreme Court confirmed Congressional authority over all annexed territories gained through U.S. imperialism.

During World War I and the First Red Scare, the Court heard several First Amendment challenges to the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917, which criminalized any speech or activity that interfered with the war effort. These decisions generally asserted that national security concerns provided grounds to limit civil liberties. The Schenck v. United States (1919) decision, for example, held that free speech may come under scrutiny if the words suggest “a clear and present danger” to the country.

Commerce

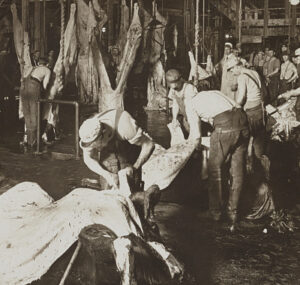

During the late 1800s, dramatic advancements in technology and transportation led to rapid urban development. New factories, mass production, steam power, and railroads revolutionized the United States’ economy, transforming it from an agrarian to an industrial one in a matter of decades. To maximize profits, companies across industries—such as steel, oil, railroad, and sugar—eliminated competitors and consolidated their resources into trusts or holding companies. This business tactic often gave one firm a monopoly and led to a concentration of wealth. With total control over the market, monopolies could, and did, exploit consumers by charging prices above competitive levels.

In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to regulate corporate activity and prevent monopolies. The act outlawed any contract or consolidation that resulted in the “restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations.” There was, however, disagreement over the scope of the act. For example, the Justice Department sued the American Sugar Refining Company for forming a monopoly over sugar refining. The Supreme Court, however, held in United States v. E.C. Knight Company (1895) that the act only applied to interstate commerce, which Congress has a Constitutional power to regulate. The act did not apply to manufacturing monopolies, like sugar refining. The decision weakened the Sherman Antitrust Act and limited the federal government’s power to break up large trusts. For the next decade, there were few anti-monopolization cases.

Discussion Questions

- To what extent did Supreme Court decisions between 1874 and 1896 impact the rights and freedoms of Black Americans?

- How did Supreme Court decisions about monopolies change over time between 1898 and 1911? What factors do you think account for this change?

- The Fourteenth Amendment was originally created in 1868 to extend rights to formerly enslaved African Americans. How else did the Supreme Court apply this amendment during this era?

- How did the Supreme Court participate in the system of checks and balances amongst the three branches of government between 1874 and 1921?

- How did Supreme Court decisions between 1874 and 1921 influence the balance of power between the federal and state governments?

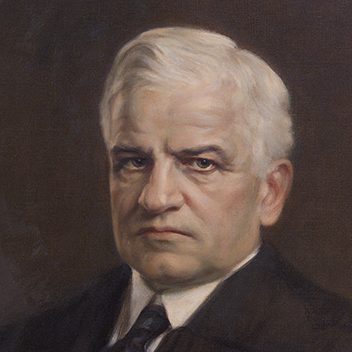

Court Justices

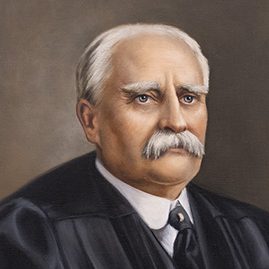

Chief Justice-

18741888

Morrison R. Waite

-

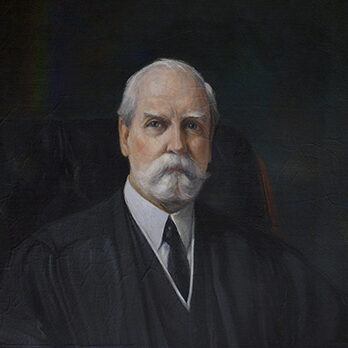

18881910

Melville Weston Fuller

-

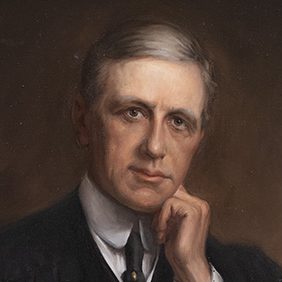

18941921

Edward Douglass White Jr.

-

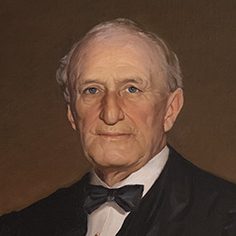

18581881

Nathan Clifford

-

18621890

Samuel F. Miller

-

18621881

Noah H. Swayne

-

18621877

David Davis

-

18631897

Stephen J. Field

-

18701892

Joseph P. Bradley

-

18701880

William Strong

-

18731882

Ward Hunt

-

18771911

John Marshall Harlan

-

18811889

Stanley Matthews

-

18811887

William B. Woods

-

18821902

Horace Gray

-

18821893

Samuel Blatchford

-

18881893

Lucius Q.C. Lamar

-

18901910

David J. Brewer

-

18911906

Henry B. Brown

-

18921903

George Shiras Jr.

-

18931895

Howell E. Jackson

-

18961909

Rufus W. Peckham

-

18981925

Joseph McKenna

-

19021932

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

-

19031922

William R. Day

-

19061910

William H. Moody

-

19101914

Horace H. Lurton

-

19101916

Charles Evans Hughes

-

19111916

Joseph Rucker Lamar

-

19111937

Willis Van Devanter

-

19121922

Mahlon Pitney

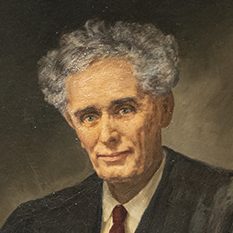

-

19141941

James Clark McReynolds

-

19161922

John H. Clarke

-

19161939

Louis D. Brandeis

Significant Cases

-

1875

United States v. Cruikshank

The Supreme Court decision that limited the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment and weakened enforcement of federal Reconstruction policies.

-

1896

Plessy v. Ferguson

The landmark decision that legalized racial segregation with its “separate but equal” precedent

-

1883

Civil Rights Cases

The Supreme Court decision that held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to be unconstitutional and paved the way for Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Jim Crow segregation.

-

1883

Ex parte Crow Dog

The Supreme Court decision that upheld Native American tribal sovereignty but paved the way for an expansion of federal authority over crimes committed in Native territory.

-

1895

United States v. E.C. Knight Company

The Supreme Court decision that limited the federal government’s power to break up monopolies.

-

1895

Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company

The Supreme Court decision that declared direct taxes on personal income unconstitutional but was nullified when Congress ratified the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913.

-

1898

United States v. Wong Kim Ark

The landmark Supreme Court decision that affirmed birthright citizenship as a protection under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

-

1901

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

The Supreme Court decision that affirmed the unrestricted legislative power of Congress in regard to treaties and weakened Native American claims to landholdings.

-

1905

Lochner v. New York

The Supreme Court’s decision that struck down state limits on work hours in bakeries.

-

1908

Muller v. Oregon

The Supreme Court decision that upheld a gender-based state labor law and set forth a legal distinction between men and women in the workplace.

-

1909

United States v. Shipp

The Supreme Court’s first and only criminal trial.

-

1911

Standard Oil Company v. United States

The Supreme Court decision that established the “rule of reason” in antitrust law and demonstrated the government’s power to regulate monopolies and increase competition.

-

1919

Schenck v. United States

The landmark decision that affirmed the federal government’s authority to interfere with the First Amendment right to free expression if the speech presented a “clear and present danger.”

Resources

-

The Election of 1876

This disputed presidential election is often claimed to mark the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction.

Read moreDownload The Election of 1876

-

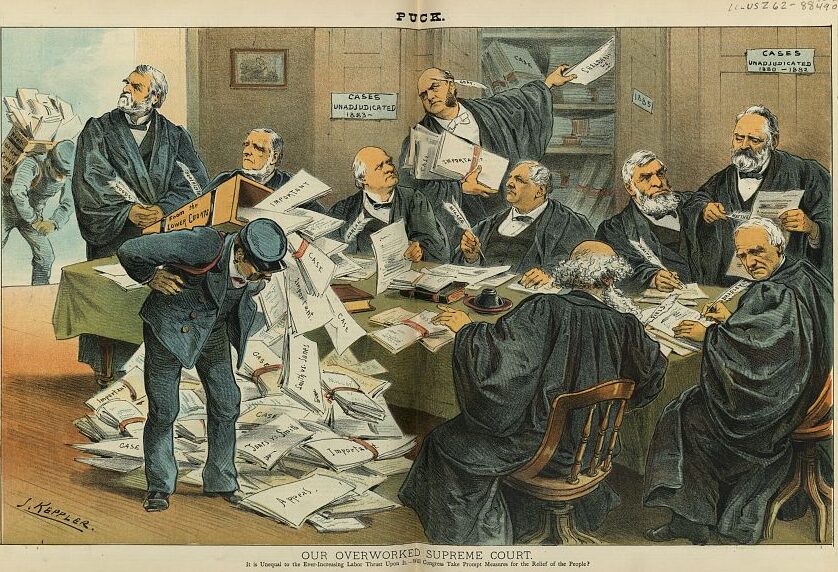

The Judiciary Act of 1891

The law that created Circuit Courts of Appeals and shaped the modern judiciary.

Read moreDownload The Judiciary Act of 1891

-

Ed Johnson v. Tennessee

The historic state court case where the mob lynching of a Tennessee man led to the first and only criminal trial at the Supreme Court of the United States.

Read moreDownload Ed Johnson v. Tennessee

Significant Events in U.S. History

Did You Know

The Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 created the framework for the third branch of government.

Read moreSources

Featured image: Keppler, Udo J., Artist. Next!. , 1904. N.Y.: J. Ottmann Lith. Co., Puck Bldg., September 7. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001695241/.

Brinkley, Alan. American History: Connection with the Past. 16th edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2023.

Cherny, Robert W. “Entrepreneurs and Bankers: The Evolution of Corporate Empires.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ap-us-history/period-6#industrial-capitalism.

Clark, Blue. Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock: Treaty Rights & Indian Law at the End of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

Corbett, P. Scott et. al. Chapter 18: Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business and Chapter 19: The Growing Pains of Urbanization. U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, 2014. https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history.

Cushman, Clare. “Protecting Women’s Health and Morals.” Essay. In Supreme Court Decisions and Women’s Rights: Milestones to Equality, 16–19. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2011.

Ely Jr., James W. The Fuller Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacies. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, Inc., 2003.

Kens, Paul. Lochner v. New York: Economic Regulation on Trial. Lawrence, KN: University Press of Kansas (1998).

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905)

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903)

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908)

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

Sinha, Manisha. The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2024.

“The Supreme Court and the Presidential Election of 1876.” Supreme Court Historical Society. https://supremecourthistory.org/schs-supreme-court-1876-election/.

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875)

Rights, Commerce, and Reform: 1874–1921