Tennessee v. Ed Johnson (1906)

Significant Case

The historic state court case where the mob lynching of a Tennessee man led to the first and only criminal trial at the Supreme Court of the United States

Background

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the Reconstruction Amendments, combined with other federal programs like the Freedmen’s Bureau, created more educational, professional, and political opportunities for African Americans. This progress, however, was short lived. Reconstruction ended after the Compromise of 1877, when the majority-Republican Congress agreed to remove its military presence from the South. The former Confederate states, which were dominated by the Democratic party, had been under martial law since 1867. In return, both sides agreed to recognize Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as the winner of the disputed 1876 presidential election.

The Civil War and the end of Reconstruction had major economic, political, and social impacts on the South. The physical destruction of war and the end of slavery left the Southern economy in ruins. While some areas were able to industrialize and become a “New South,” most places still relied on Black labor. Slavery was replaced with sharecropping and tenant farming. Additionally, Southern states and local lawmakers passed legislation restricting the freedoms and voting rights of African Americans. White supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan used violence and intimidation to enforce a racial caste system.

Even after Reconstruction ended, Chattanooga, Tennessee was more progressive than the majority of the South. The city never voted to secede from the United States during the Civil War. It became a safe haven for formerly enslaved people after the Union Army occupied the city in 1863. Still, Chattanooga was no exception to the racist policies and violence that most Southern towns experienced during this time. The city implemented Black Codes and voting restrictions, reducing Black representation in local government. Race-base murders, known as lynchings, increased across Southern towns between 1850 and 1930, and Chattanooga experienced three during that time. Racial tensions in the city reached a climax between 1905 and early 1906, culminating with the lynching of a Black man named Ed Johnson.

The Investigation of Ed Johnson

On January 23, 1906, 21-year-old Nevada Taylor took a streetcar from her bookkeeping job in downtown Chattanooga to her home on the outskirts of town. When she arrived, she began her usual walk home. Shortly after 6:30 p.m., an unknown man sexually assaulted Taylor on her way home. Her father immediately called Sheriff Joseph Shipp and his deputies to investigate the crime.

Taylor did not get a good look at her attacker, but she remembered he had a soft, kind voice. Investigators struggled to find much other than a black leather strap possibly used to strangle Taylor during the attack. Initially, the officers accused and arrested James Broaden, but Broaden maintained his innocence. Sheriff Shipp offered a $50 reward on January 24. Other businesses and community members added to the reward and it grew to $375 (over $12,000 in 2024).

The next day, Will Hixson, a white man who worked near the crime scene, called the sheriff and reported that he had seen a Black man “twirling a leather strap around his finger” near the streetcar stop shortly before 6:30 p.m. the night of the attack. Hixson later identified the suspect as Ed Johnson, and Sheriff Shipp made the arrest.

The sheriff questioned Johnson for over three hours. In those days, the law did not require an accused person to have access to an attorney during police questioning. Johnson claimed to know nothing of the attack.

News of the arrest spread. Sheriff Shipp moved Johnson and Broaden to Nashville, 134 miles away, for their safety. That night, a mob of over 1,500 armed people gathered outside the jail in Chattanooga looking for Johnson. They demanded he be released so he could face immediate punishment for the assault of Nevada Taylor. Judge McReynolds appeased the mob by allowing some members to confirm that Johnson was not there. The judge promised the mob that he would hold the trial and said that he hoped for an execution within 10 days.

On January 27, Taylor traveled to Nashville to identify her attacker. Placed together in a cell, James Broaden and Ed Johnson both spoke to Taylor to provide voice samples. Taylor stated that Johnson had the “same soft, kind voice” of her attacker. Later that day, a grand jury convened by Judge McReynolds indicted Ed Johnson for the rape of Nevada Taylor.

The Trial

Judge McReynolds scheduled the trial for February 6, 1906, 10 days after Johnson’s indictment. Johnson could not afford a lawyer, so Judge McReynolds appointed him one, as Tennessee law required. He appointed three white attorneys to defend Johnson, two of whom were inexperienced in criminal defense. The team rushed to gather evidence, find alibis, and speak with their client, who was still being held in the Nashville jail over 100 miles away.

Two days of testimony gave the jurors a vast amount of information to consider. The defense’s cross examination of Nevada Taylor established that she passed out for 15 minutes during the attack. Multiple witnesses testified that it was extremely dark out that evening. Will Hixon, who reported Johnson to the police, testified that he saw him with the leather strap near the street car. On cross examination, the defense established that Hixon was motivated by the $375 reward. Sheriff Shipp recounted the crime in his testimony, but upon cross examination could not swear that Taylor’s identification of Johnson was 100 percent certain. When Johnson took the stand, he denied attacking Taylor and maintained his innocence. He also supplied his alibi—that he was working at a local saloon—and several witnesses who could support him. Throughout the entire proceeding, court spectators heckled and booed and heckled the defense team, their witnesses, and Johnson. Judge McReynolds did not intervene.

On the third and final day of the trial, the jury grew frustrated. The prosecution called additional witnesses to discredit the defense’s case. The back-and-forth nature of the arguments was confusing, and finally the jury asked Judge McReynolds if it could hear from Nevada Taylor again. She once again identified Johnson as her attacker. When pressed, though, she could not swear for a fact that it was him. This only increased tensions. At one point, a juror leapt from his seat and threatened Johnson. Judge Reynolds then called for a lunch break.

After lunch, both sides gave their closing statements. The defense questioned the motives of the investigation, emphasizing the monetary reward and the fact that Sheriff Shipp may be thinking about reelection. Additionally, it reminded the jury that numerous witnesses testified to the extreme darkness the evening of the attack, making it impossible for Taylor to accurately identify her attacker. The prosecution, on the other hand, humanized Taylor, demonized Johnson, and reminded the jury of the crime’s brutality.

The Decision

After six hours of deliberation, the all-white jury was split 8-4, with four favoring innocence. Judge McReynolds dismissed them for the evening, worried about the possibility of a hung jury. He discussed his concerns privately with Sheriff Shipp and the district attorney, who argued for the prosecution. Johnson’s attorneys were not present.

The names of the jurors were printed in the newspaper the next morning. Having their identities published endangered their safety. Anyone who disagreed with their verdict could find them and retaliate. When the jury returned to court that day, they quickly reached a verdict of “guilty.” Judge McReynolds sentenced Ed Johnson to death by hanging on March 13, 1906.

After Judge McReynolds issued his sentence, Johnson’s father pleaded with the local Black attorney Noah Parden to appeal his son’s case. Parden and his law partner, Styles L. Hutchins, successfully appealed Johnson’s case to the Supreme Court of the United States. Justice John Marshall Harlan, who oversaw the Sixth Circuit, granted a stay of execution for Johnson and moved to have the case heard as soon as possible.

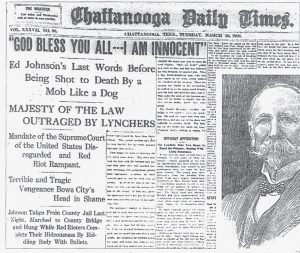

Hours later, a lynch mob broke into the jail where Johnson was being held. The mob seized him from his cell and dragged him to the Walnut Street Bridge. They hung him from the bridge and, when the rope snapped, shot him to death. His last words were, “God bless you all! I am innocent.”

Impact

Authorities quickly discovered that Sheriff Shipp had sent home all his deputies for the evening, leaving the jail almost entirely unattended. His negligence was found to be a direct violation of the Supreme Court’s stay of execution. Johnson’s case never made it to the Supreme Court, but Sheriff Shipp’s did. In 1909, the Supreme Court unanimously found Sheriff Shipp and six other defendants guilty of contempt of court. United States v. Shipp was the first and only time the Supreme Court, which usually only hears appeals from the highest federal and state courts, sat as a trial court.

Discussion Questions

- Why was it significant in this case that Sheriff Shipp and community members offered a reward for information leading to Nevada Taylor’s attacker?

- Do you think any of the trial procedures were questionable or unfair? Why or why not?

- Why do you think it was significant that the names of the jurors were printed in the newspaper?

- How does Ed Johnson’s case reflect the social and political climate of the South after the end of Reconstruction?

Sources

Special thanks to the Honorable Curtis L. Collier for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Front page of the Chattanooga Daily Times on March 20, 1906. “A Supreme Case of Contempt.” ABA Journal. https://www.abajournal.com/gallery/supremecontempt.

Curriden, Mark and Leroy Phillips. Contempt of Court: The Turn-of-the-Century Lynching That Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism.

Hindley, Meredith. “Chattanooga versus the Supreme Court: The Strange Case of Ed Johnson.” Humanities 36, no. 6 (November/December 2014). National Endowment for the Humanities. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2014/novemberdecember/feature/chattanooga-versus-the-supreme-court.