The Judiciary Act of 1891

Impactful Policy

The law that created Circuit Courts of Appeals and helped shape the modern judiciary.

The United States Courts of Appeals are 13 courts located in cities across the country. They hear appeals from decisions of the United States district courts. Because the United States Supreme Court typically decides fewer than 100 cases a year, the Courts of Appeals are the final stage of almost all federal court cases.

Background

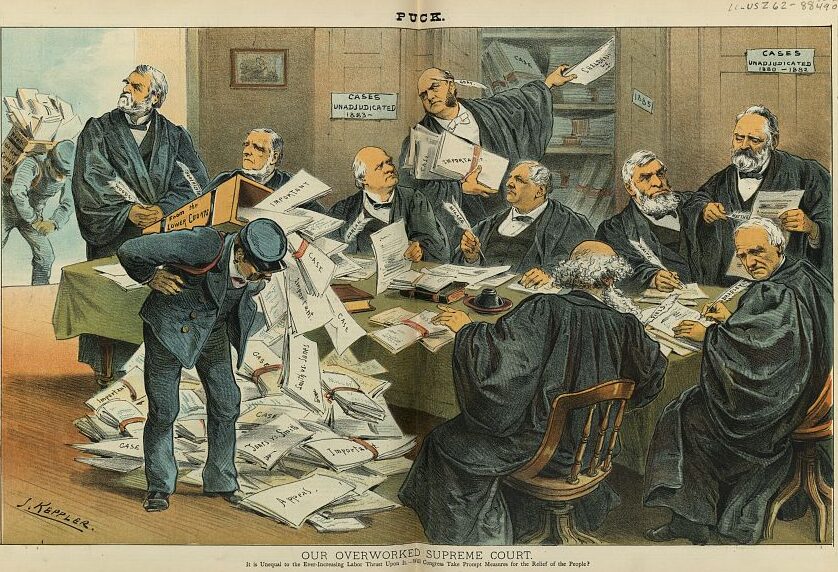

In the 1870s and 1880s, federal court dockets expanded due to the rapid growth of industry and transportation, as well as the controversy surrounding the rights of newly freed slaves and their descendants. Additionally, new laws expanded the types of cases that federal courts could decide. The Supreme Court was not immune to the expanded workload—Justices also encountered an overwhelming number of appeals. They were further burdened by requirements that Justices not only decide their Supreme Court cases but also travel the country sitting as circuit court judges (known as circuit riding). Congress required the Court to review most of the appeals, resulting in years-long backlogs.

Article III of the U.S. Constitution established the authority and responsibilities of the federal judiciary, but it authorized Congress to detail the organization of the court system. Even before the increase in federal court workload after the Civil War, Congress had taken some action to adjust the court system, adapting it to the growing nation’s judicial needs. Those actions built upon the 1789 Judiciary Act, which organized the system in the country’s first year under the Constitution.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 organized the Supreme Court and divided the country into three judicial circuits, each comprising multiple districts. Each district had two trial-level courts: a district court, presided over by a district judge (mainly to decide admiralty cases), and a circuit court, which heard all types of cases authorized by Congress. Few cases reached the Supreme Court in its early years, and the Term lasted only a month. The Justices spent more time traveling to and hearing circuit court cases than sitting on the Supreme Court bench. Justices presided over cases in their assigned circuit alongside the local district judge. Serving on the circuit courts allowed the Justices to establish a sense of federal judicial power throughout the country. They educated local citizens about federal law and learned firsthand how local lawyers and judges viewed the law and the judicial process. By designating the Justices as circuit judges, Congress also saved the country money by eliminating the need for a separate set of judges. However, “riding the circuit” was not without its problems. Justices often wrote to both the President and Congress, expressing their frustration with the circuit riding system. They complained of the long, fatiguing, and dangerous trips far from home, as well as occasionally reviewing the decisions they made as circuit judges, which at least appeared to be a conflict of interest. Justices also traveled to their circuits at their own expense. Associate Justice James Iredell suggested to Chief Justice John Jay that all six Justices forfeit $500 of their annual salary ($3,500 for associate Justices and $4,000 for the Chief Justice) to help offset the costs of hiring circuit judges. In today’s dollars, the amount Iredell was willing to give up is about $18,000.

In the closing hours of John Adams’s presidency, Congress attempted to reform the court system with the Judiciary Act of 1801. The act reorganized the federal courts’ three circuits into six, and for each, created a new office of circuit judge. Circuit riding would now be the responsibility of the circuit judges. However, at the request of the new President, Thomas Jefferson, Congress replaced the act with the Judiciary Act of 1802, retaining the six circuits but abolishing the 1801 Act’s separate circuit judgeships. The act also reinstated the Justices’ circuit-riding duties, requiring Justices to hear cases in the districts of their assigned circuits at least once a year, alongside the local district court judge.

In 1807, Congress mandated that Justices appointed to the new Seventh Circuit must come from Ohio, Kentucky, or Tennessee. This requirement aimed to ensure the Justice serving the Seventh Circuit was familiar with the local customs and laws of those states. Throughout the 19th century, numerous judicial reform proposals submitted to Congress failed to gain enough support to become law. However, in 1869, Congress granted circuit courts appellate jurisdiction in district court criminal cases. Lawmakers also reduced the frequency of circuit riding for Justices by creating a separate circuit judgeship for each circuit. Supreme Court Justices were only required to sit on circuit courts once every two years.

Nevertheless, the basic design of the 1789 Act required significant reform. After the Civil War, the nation began to confront President Abraham Lincoln’s 1861 warning that “the country has outgrown our present judicial system.” The backlog of cases on the dockets continued to grow. In 1860, the Court had 310 cases on its docket; by 1890, it had 1,816, including 623 new cases filed that year. For nearly 30 years, judges, lawyers, legislators, and others debated how to update the system. Numerous political factions disagreed over the value of expanding the federal judiciary to make it more effective. One group, based mainly in the House of Representatives and drawing strength from the South and the West, wanted to retain the traditional form of the federal courts but restrict their jurisdiction. They believed that the courts were too sympathetic to commercial interests and too eager to frustrate state legislative efforts to help farmers and workers. Another coalition, with strength in the Senate and based in the East, wanted to broaden the federal courts’ capacity so they could exercise the expanded jurisdiction created in the wave of nationalist sentiment after the Civil War.

The Judiciary Act of 1891

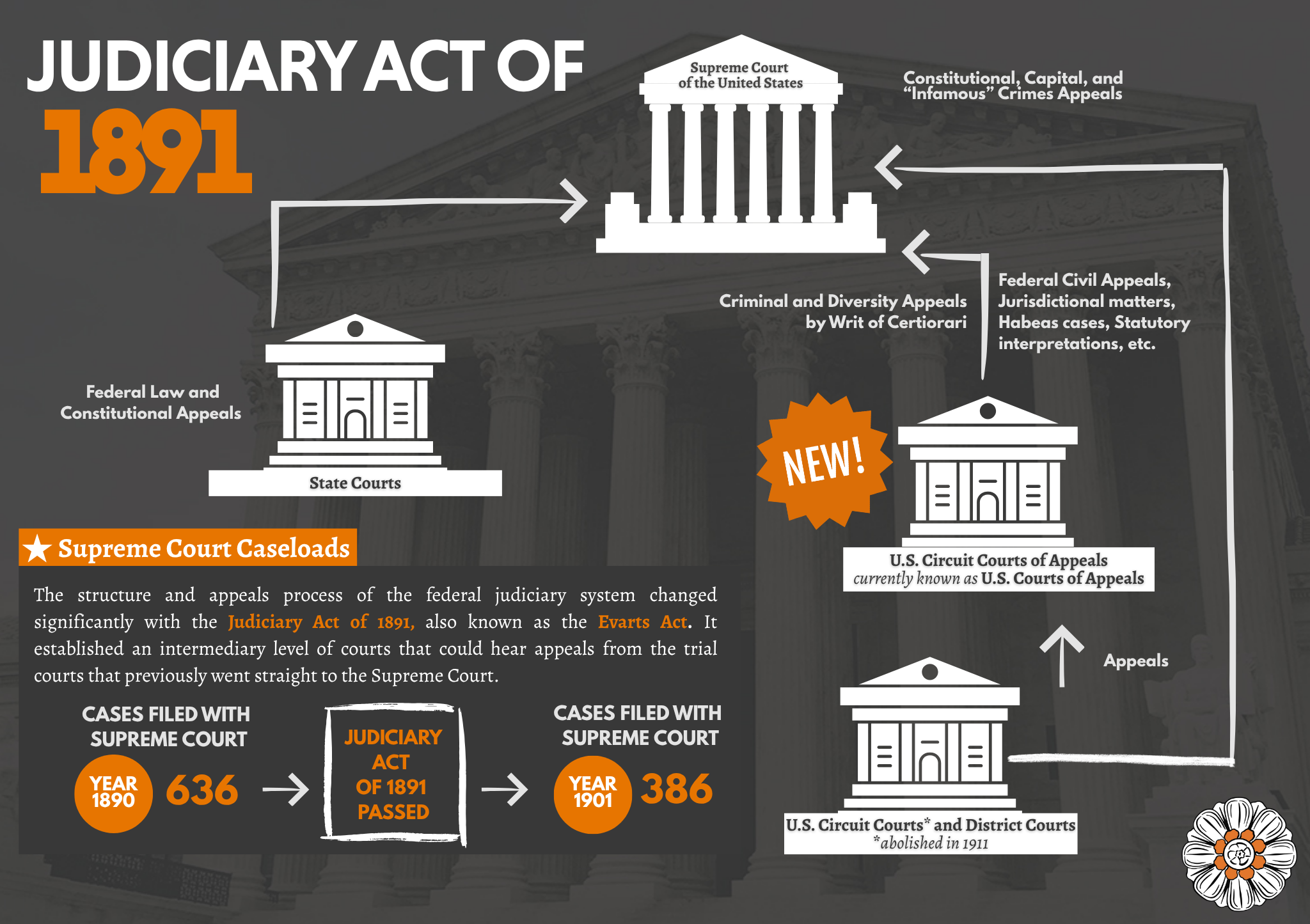

Those arguments led to a significant revision in 1891, creating a system that resembles today’s judiciary. The Senate Judiciary Committee requested that Chief Justice Melville Fuller and the associate Justices submit information on their responsibilities and offer recommendations to improve the system. The House of Representatives crafted a bill that eliminated the circuit courts and gave the Court some control over its docket, allowing it to limit the number of cases heard each year. Senator William Evarts of New York proposed modifications to the bill. His plan created a new level of courts—Courts of Appeals—one in each of the nine circuits. Each would be staffed with two circuit judges, with either the circuit Justice or a district judge creating the three-judge appellate court. Matters such as contract disputes, patent cases, personal injury suits, and admiralty cases would be appealed to the new appellate courts. Those cases would no longer have an automatic right of appeal directly to the Supreme Court. The Act also established the district courts as the system’s uniform first level of jurisdiction. The circuit courts continued to exist until Congress abolished them in 1911.

The 1891 Act also initiated the gradual shift from a Supreme Court that was required to hear almost every case brought before it, to today’s situation, where the Justices have nearly complete discretion over which of the approximately 8,000 cases presented to them each year they will decide. Today, in almost all federal cases, decisions of the Courts of Appeals are final. To request the Supreme Court to review a decision of a court of appeals (or a state supreme court), parties must file a petition for a writ of certiorari, and the Justices decide whether to hear the case. The appeals courts established by the Judiciary Act of 1891 created a filter, allowing the Supreme Court to limit its docket to specific types of cases. Those cases include conflicts over the interpretation of the Constitution and statutes, technical questions of procedure and jurisdiction, and headline-generating cases on civil rights and the separation of powers. Multiple Congressional statutes have helped to reduce the Court’s caseload and improve its efficiency since the Judiciary Act of 1891. Between 1890 and 1901, the number of cases filed with the Supreme Court dropped by almost 40 percent. The Supreme Court’s limited jurisdiction, established by the 1891 Act, has been expanded by subsequent 20th-century legislation. This led to an expansion of the appellate and district court caseloads, necessitating the hiring of additional judges.

Today, the only evidence of the old circuit-riding system is the statutory requirement that the Supreme Court assign its members to serve as circuit Justices in one or two of the 13 circuits. The primary role of the circuit Justices is to receive emergency petitions (often seeking to delay execution of a death sentence), on which they may rule provisionally and refer the petition to the entire Court. Justices who retire from full-time active service, known as “senior Justices,” sometimes serve temporarily on lower federal courts.

The Judiciary Act of 1891 prompted a series of Congressional acts that modified the federal judiciary, shaping the court system as it exists today.

Discussion Questions

- How did changes in the United States after the Civil War impact the Supreme Court’s caseload?

- Justice James Iredell suggested that all Justices sacrifice $500 of their salaries to eliminate the requirement that they ride circuit (by funding separate circuit judges). What percentage of their annual salaries was this? Would that have been fair? Why or why not?

- Why did it take Congress so long to change and eventually abolish the circuit riding system?

- Which of the changes made by the Judiciary Act of 1891 do you think had the most significant impact on the Supreme Court? Explain.

- How did the creation of the Courts of Appeals impact the Supreme Court docket?

- How did the federal judiciary change over time to reflect the evolving needs of the United States?

Extension Activity

Create a timeline of 10 important events in the development of the federal judicial system. Use this resource, along with Riding the Circuit and The Judiciary Act of 1789, to help you.

-

Infographic – The Judiciary Act of 1891

Use this infographic to help students understand the development of the federal Courts of Appeals.

Download Infographic – The Judiciary Act of 1891

Sources

Special thanks to Russell R. Wheeler, nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Governance Studies Program, for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Keppler, Joseph Ferdinand, Artist. Our overworked Supreme Court / J. Keppler. , 1885. N.Y.: Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann, December 9. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011661363/.

Cave, Gilbert T. “Judiciary Acts of 1801-1925: EBSCO.” EBSCO Information Services, Inc. | www.ebsco.com, 2022. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/law/judiciary-acts-1801-1925.

Cushman, Clare. An illustrated guide to the Supreme Court. Washington, D.C.: Article Books, an imprint of the Supreme Court Historical Society, 2024.

“Federal Judicial Center.” Jurisdiction: Appellate | Federal Judicial Center. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.fjc.gov/history/work-courts/jurisdiction-appellate.

“Federal Judicial Center.” Landmark Legislation: Abolition of U.S. Circuit Courts | Federal Judicial Center, March 3, 1911. https://www.fjc.gov/history/legislation/landmark-legislation-abolition-us-circuit-courts.

“Federal Judicial Center.” Landmark Legislation: Judiciary Act of 1802 | Federal Judicial Center, April 29, 1802. https://www.fjc.gov/history/legislation/landmark-legislation-judiciary-act-1802.

“Federal Judicial Center.” Landmark Legislation: U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals | Federal Judicial Center, March 3, 1891. https://www.fjc.gov/history/legislation/landmark-legislation-us-circuit-courts-appeals.

Glick, Joshua. “Riding the Circuit.” Supreme Court Historical Society, April 2003. https://www.supremecourthistory.org/assets/SCHS_publications-circuitriding.pdf.

“The Evarts Act: Creating the Modern Appellate Courts.” United States Courts. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/educational-activities/us-courts-appeals-and-their-impact-your-life/evarts-act-creating-modern-appellate-courts.

“The Federal Judiciary System, 1891: U.S. Capitol – Visitor Center.” The Federal Judiciary System, 1891 | U.S. Capitol – Visitor Center. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/artifact/federal-judiciary-system-1891.

Wheeler, Russel R., and Cynthia Harrison. “Creating the Federal Judicial System.” Federal Judicial Center. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.fjc.gov/sites/default/files/2012/Creat3ed.pdf.