Affirming Judicial Independence

Through a series of landmark decisions, the Justices of the Marshall Court affirmed the judicial independence of the federal courts, the authority of the Supreme Court, and ensured that the Judicial Branch was an equal branch of the federal government.

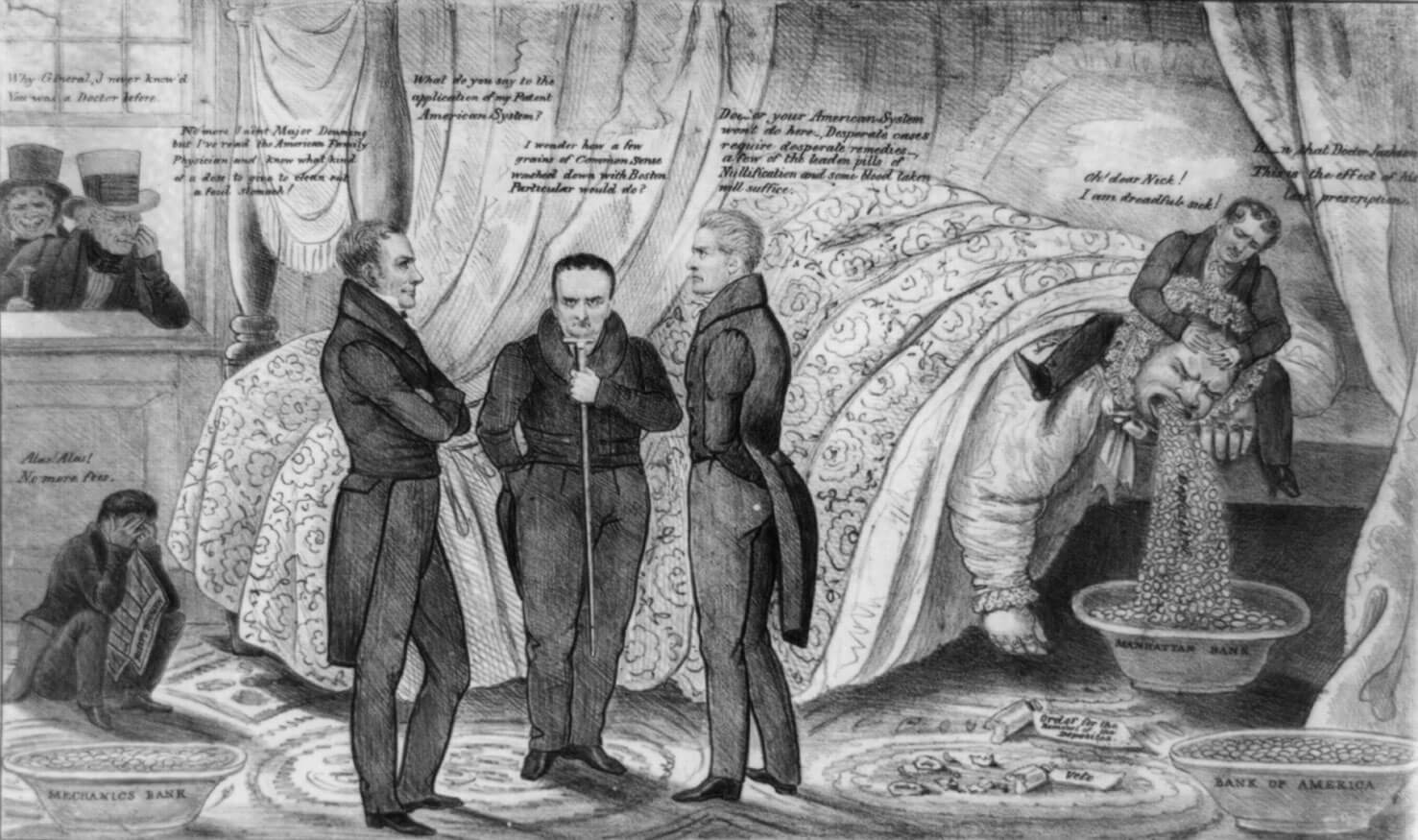

The Supreme Court affirmed the legitimacy of the Bank of the United States (depicted here as a large woman vomiting coins to state banks) when Maryland mounted a challenge in 1819. Library of Congress

The Supreme Court affirmed the legitimacy of the Bank of the United States (depicted here as a large woman vomiting coins to state banks) when Maryland mounted a challenge in 1819. Library of Congress

“My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.”

– John Adams, President

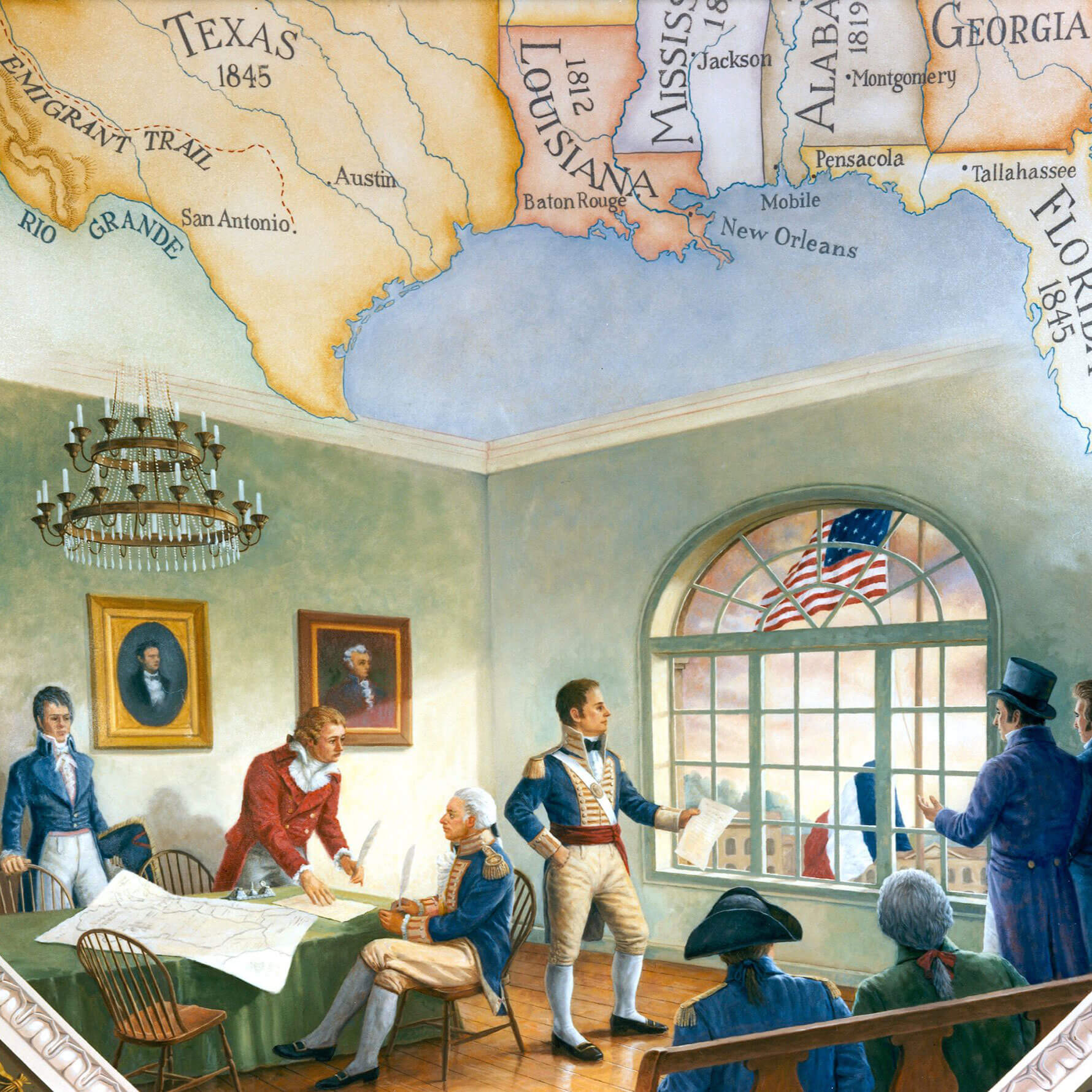

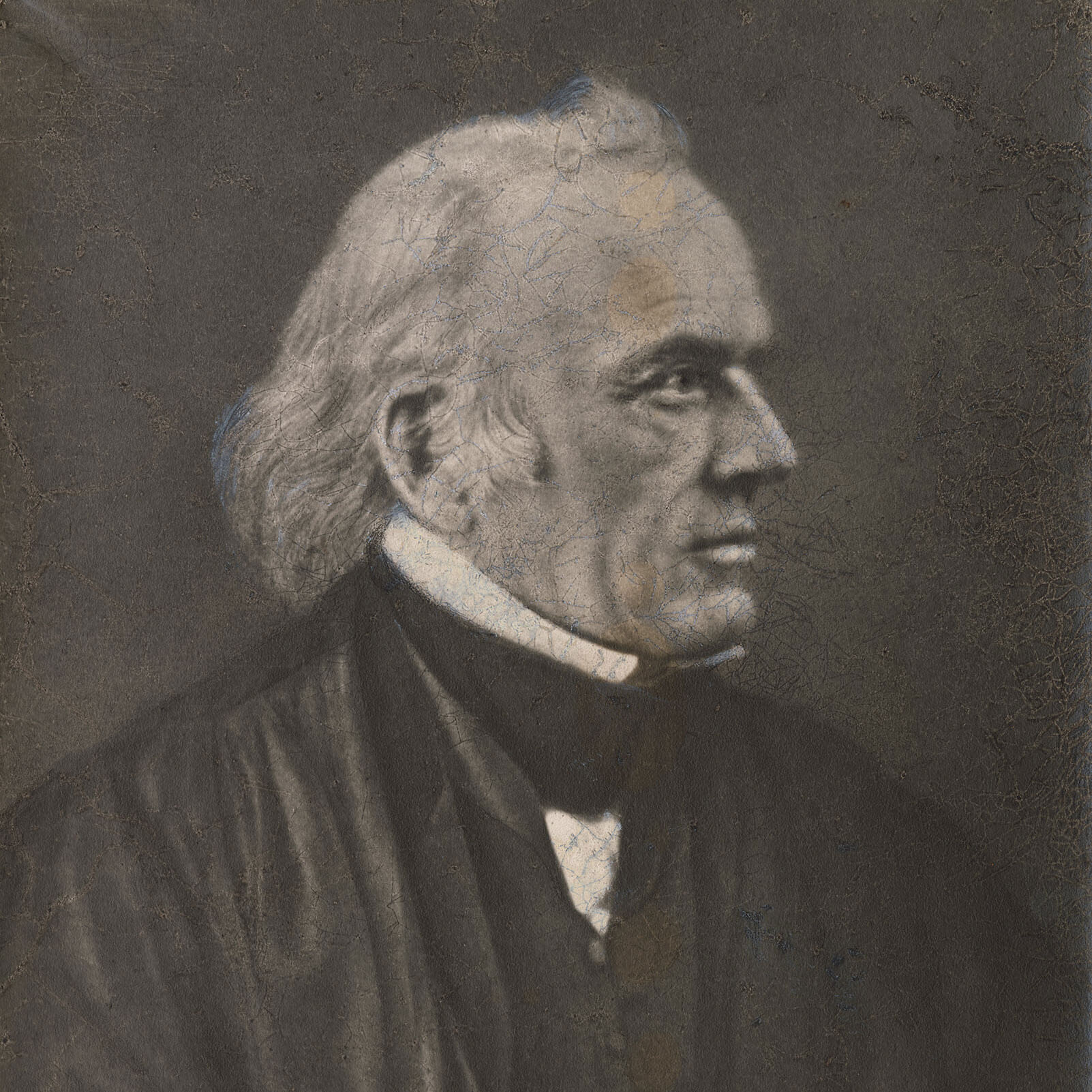

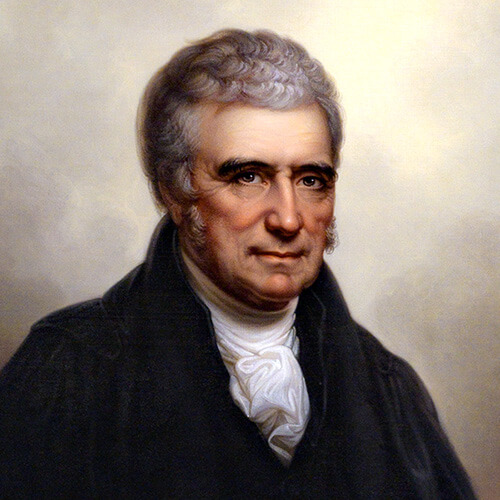

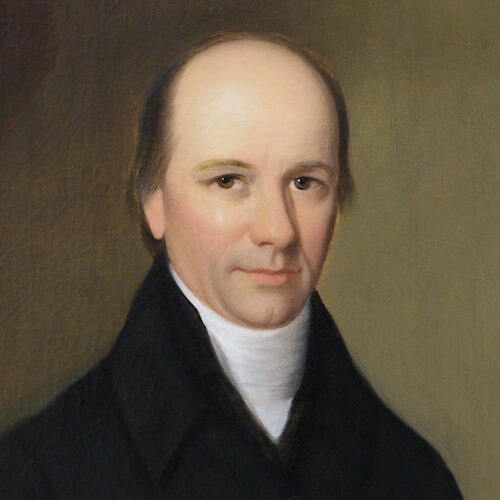

In the early years of the United States, the country wrestled with the scope and powers of each of the three branches of government established under the Constitution–Legislative, Executive, and Judicial–as well as the relationship between the national, or federal, government and the state governments. At the center of these struggles for the Judicial Branch and the Supreme Court of the United States was its Chief Justice, John Marshall. President John Adams appointed Marshall to serve as Chief Justice in 1801 to succeed Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth (who had been given a new appointment as Minister to France). Marshall and the Court faced many formative issues, both immediately and over the 34 years he served as Chief Justice. Those issues ranged from the practical, including where the Court would meet and hear cases, to the profound, including the Court’s authority to review whether laws passed by Congress were Constitutional and whether it could review decisions from state courts that posed Constitutional issues. For much of his tenure, Chief Justice Marshall was able to unify the Justices and issue unanimous decisions, thereby increasing the Court’s power and visibility.

Almost immediately upon his appointment, Marshall faced a defining moment for the country’s form of government and the Supreme Court’s role in it. When President Adams lost his re-election bid to Thomas Jefferson in 1800, the country experienced its first transfer of power from one political party to another. As Adams, a Federalist, left office he and Congress attempted to secure their federalist legacy by passing the Judiciary Act of 1801 which enabled him to appoint numerous life-tenured judges and magistrates to the Judiciary. Some of the “last-minute” appointments by Adams were not delivered before President Jefferson took office and he did not honor those appointments. One appointment was for William Marbury who then sought to enforce his appointment by bringing an enforcement action to the Supreme Court. The case, Marbury v. Madison, has become one of the most well-known and influential decisions issued by the Court. Chief Justice Marshall wrote for the Court that although Marbury was entitled to his appointment, the provision of law in the Judiciary Act of 1801 on which Marbury relied to enforce his commission was unconstitutional. In short, the Court demonstrated that it had the authority to review Acts of Congress for their constitutionality. This is still an enormous power vested in the Judicial Branch that gives it equal status with the Legislative (Congress) and Executive (President) Branches.

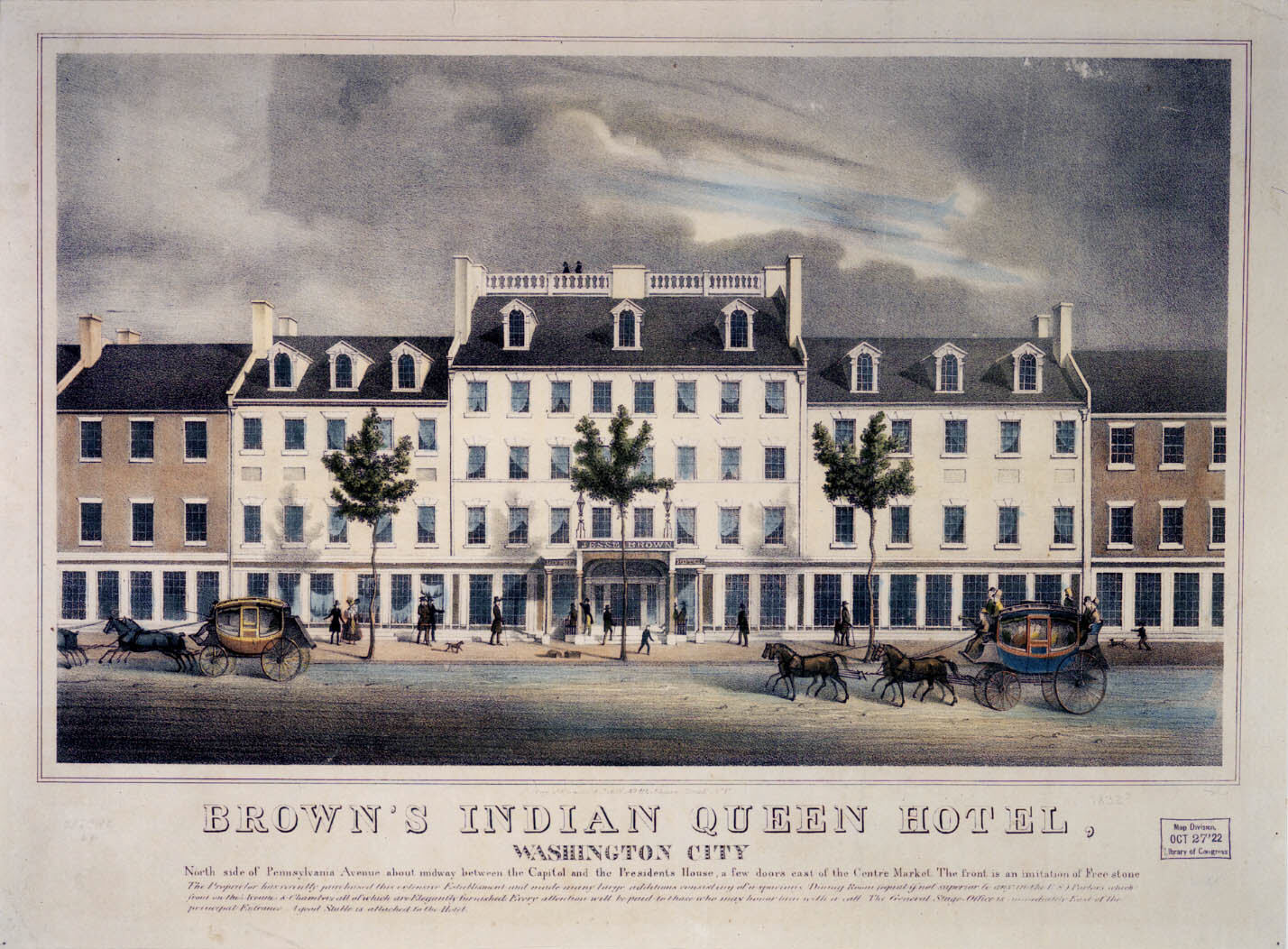

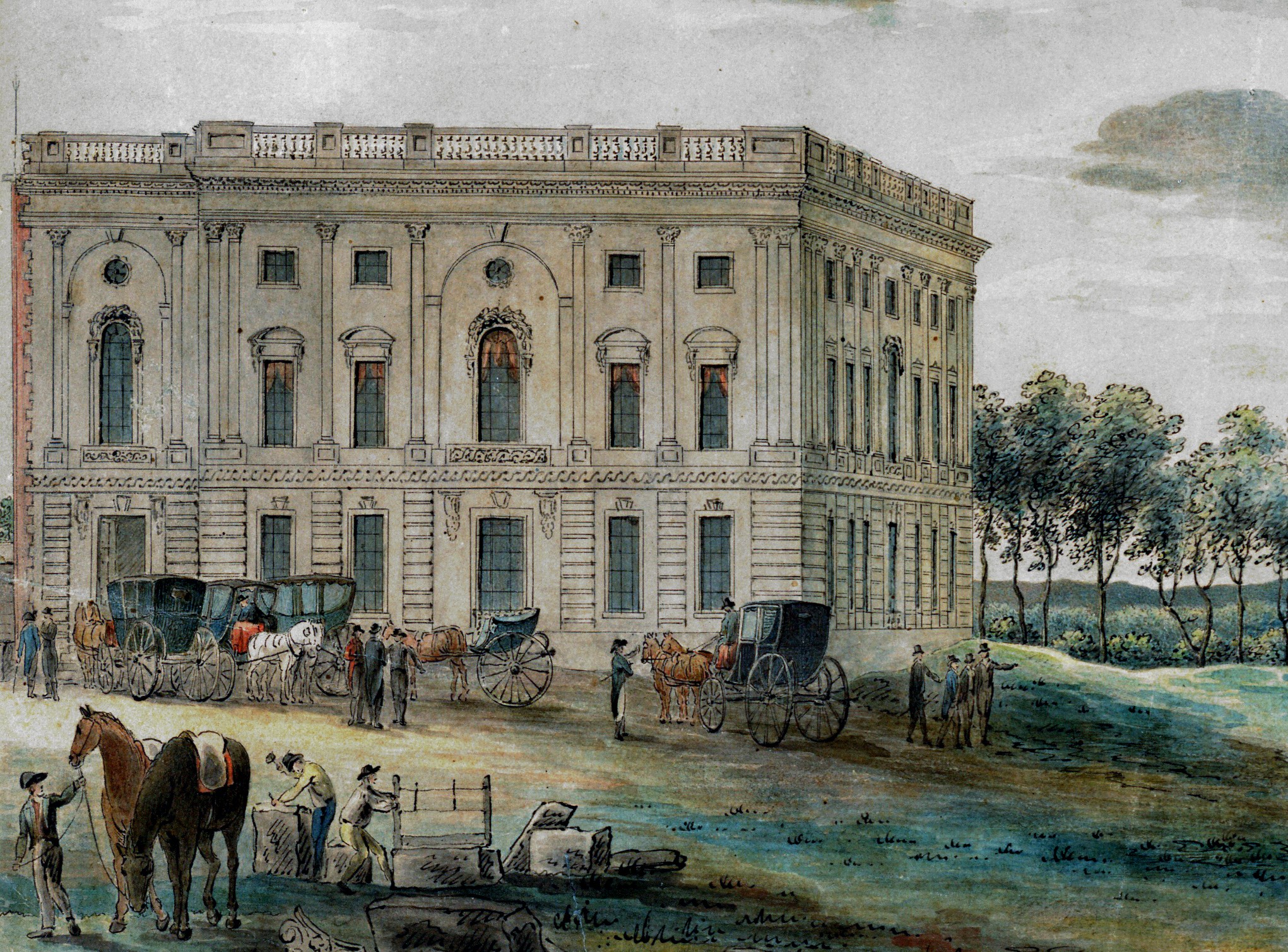

One of the practical issues facing Marshall and the Supreme Court early in Marshall’s tenure was where the Court would sit. For a time, the Supreme Court was in New York, then moved to Philadelphia, before finally settling in the basement of the new Capitol Building in 1810 in the District of Columbia. The Supreme Court was forced to relocate temporarily after the United States’ entrance into the War of 1812, when the British set fire to the Capitol in 1814.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think President Adams viewed the appointment of Chief Justice Marshall as a “gift”?

- How did the status and authority of the Supreme Court evolve during this era?

- Describe the impact of the election of Andrew Jackson on both the Supreme Court and the federal government.

- What actions by Marshall Court Justices helped the Supreme Court to establish itself as a co-equal branch of government?

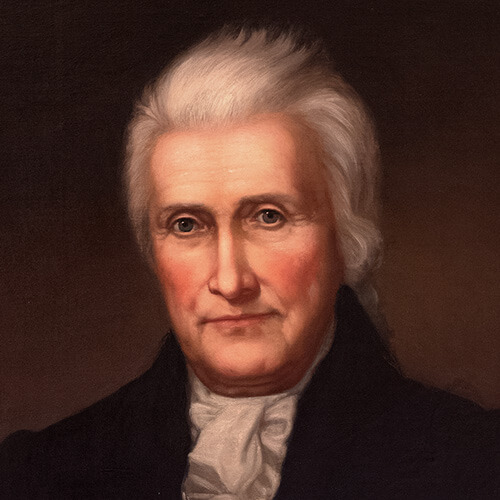

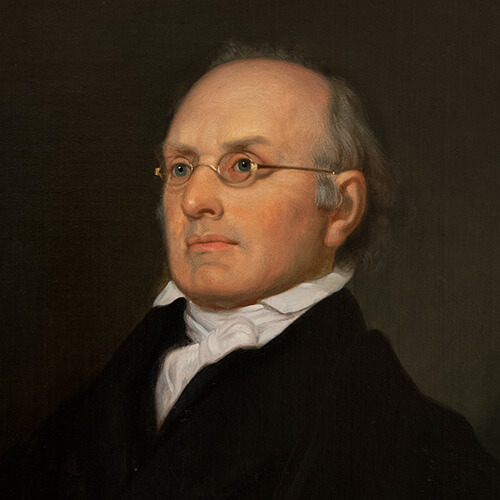

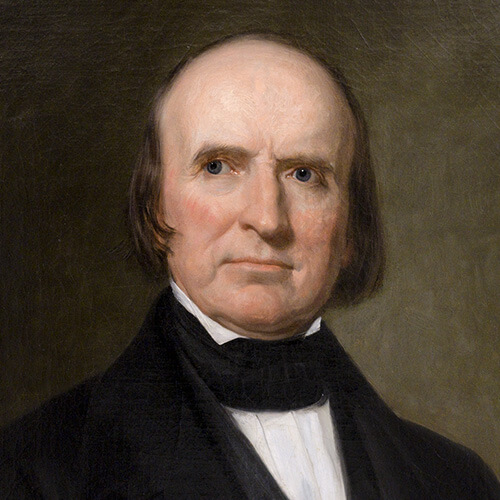

Supreme Court Justices

Chief Justice-

18011835

John Marshall

-

17991829

Bushrod Washington

-

18001804

Alfred Moore

-

18041834

William Johnson

-

18071826

Thomas Todd

-

18061823

H. Brockholst Livingston

-

18111835

Gabriel Duvall

-

18121845

Joseph Story

-

18231843

Smith Thompson

-

18261828

Robert Trimble

-

18291861

John McLean

-

18301844

Henry Baldwin

Significant Cases

-

1803

Marbury v. Madison

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that established judicial review and the importance of separation of powers.

-

1810

Fletcher v. Peck

The first time the Supreme Court declared a state law unconstitutional and a formative decision interpreting the Commerce Clause.

-

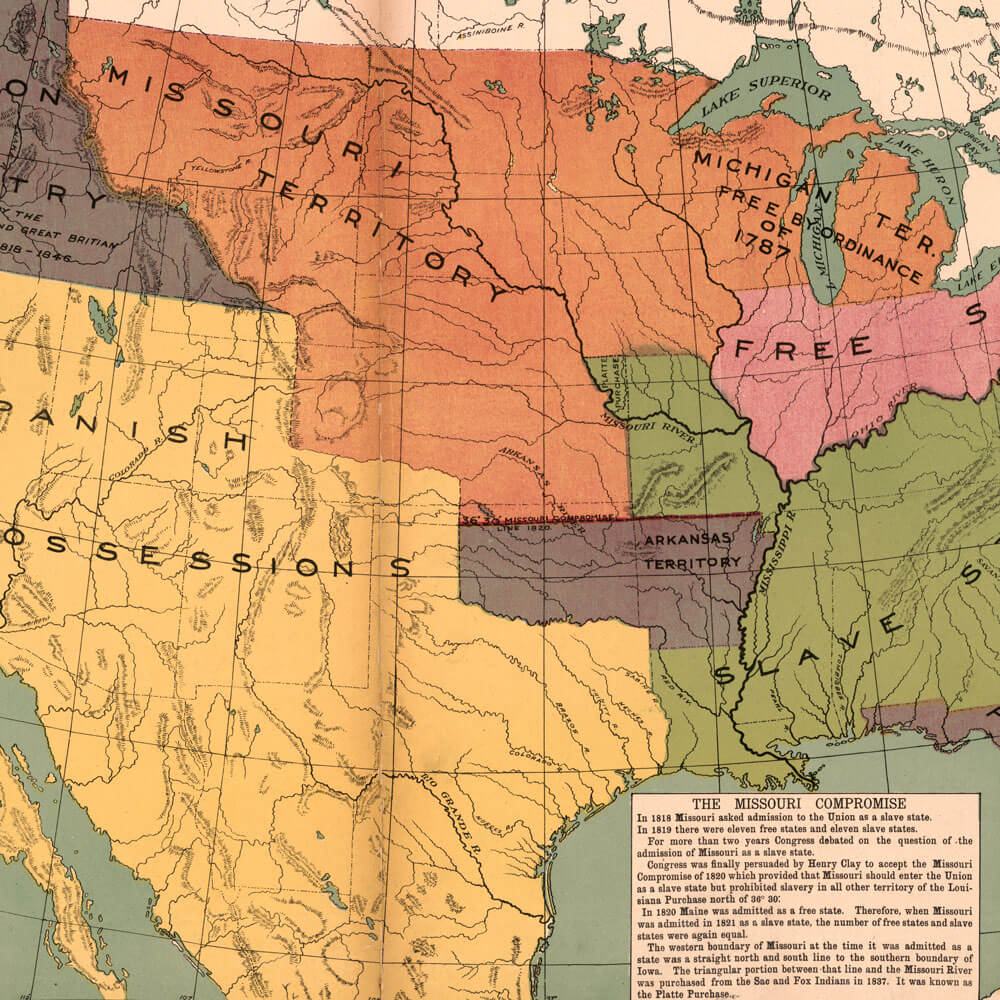

1819

McCulloch v. Maryland

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that determined that Congress had the implied powers to create a national bank.

-

1821

Cohens v. Virginia

The Supreme Court’s opinion that clarified its appellate jurisdiction over state laws.

-

1824

Gibbons v. Ogden

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that determined that the Commerce Clause of the Constitution grants the federal government the power to determine how interstate commerce is conducted.

-

1831

The Cherokee Nation Cases

The lawsuits that forced the examination of the relationship between law and politics, particularly with respect to the Supreme Court’s ability to enforce its judgment during the early years of the Republic.

-

1833

Barron v. Baltimore

John Marshall’s last opinion which addressed the existing parameters of federalism in relation to the states.

Resources

-

Boarding Houses: The Unofficial Headquarters of the Early Supreme Court

These local establishments served as a dwelling and meeting place for the early Supreme Court Justices

Read MoreDownload Boarding Houses: The Unofficial Headquarters of the Early Supreme Court

-

Dissents in the Early Supreme Court

A brief history of dissents, the Marshall Court’s first dissent, and Chief Justice John Marshall’s first and only dissent.

Read MoreDownload Dissents in the Early Supreme Court

-

Riding the Circuit

The rather challenging additional responsibility held by Supreme Court Justices until the early 1900s.

Read MoreDownload Riding the Circuit

-

Women and the Early Court

The significant roles of Supreme Court wives during the first decades of the Court.

Read MoreDownload Women and the Early Court

Significant Events In U.S. History

Here’s what was happening in the U.S. during this era.

Quick Downloads

-

Affirming Judicial Independence

Document -

Life Story: John Marshall

Document -

Life Story: Thomas Todd

Document -

Life Story: Joseph Story

Document -

Life Story: Daniel Webster

Document -

Life Story: Bushrod Washington

Document -

Fletcher v. Peck

Document -

Cohens v. Virginia

Document -

Barron v. Baltimore

Document

Sources

Appleby, Joyce, National Expansion and Reform (1815-1860), Gilder Lehrman, https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/essay/national-expansion-and-reform-1815%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9C1860?period=4

Davis, Alan Taylor, The New Nation (1783-1815), Gilder Lehrman, https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/essay/new-nation-1783%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9C1815?period=3

Killenbeck,Mark R., M’Culloch v. Maryland: Securing a Nation (Landmark Law Cases and American Society), University of Kansas Press, 2006.

Supreme Court Historical Society, The Marshall Court 1801-1835, https://supremecourthistory.org/history-of-the-courts/the-marshall-court-1801-1835/

All portraits and images of the Marshall Court Justices are from the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Affirming Judicial Independence: 1801–1835