Boarding Houses

These local establishments served as a dwelling and meeting place for the early Supreme Court Justices.

The Unofficial Headquarters of the Early Supreme Court

In the early 1800s, Washington was not a bustling capital city. Unlike the two developed cities that had previously served as the nation’s capital, New York and Philadelphia, it lacked any significant infrastructure and Thomas Jefferson described the area as, “hills, valleys, morasses, and water.” In 1800, when Congress began the process of moving to the swampy federal district, there were few paved roads and the city was being haphazardly built. The Capitol Building and the President’s mansion (later termed the White House) were unfinished. Animal life roamed the streets. In sum, there was little to draw American citizens to the capital city other than necessary political business. Thus, Washington was composed of two main groups–a seasonal, male population who were obliged to reside there while they conducted the business of the United States and a small, working-class population, including enslaved people, who ran local businesses and cared for the federal representatives while they were in town.

Like the rest of the temporary residents, the Supreme Court Justices typically left their families at home when the Court was in session, electing to stay in local boarding houses and hotels instead of purchasing or renting larger family quarters. One social observer remarked:

There are few families that make Washington their permanent residence, and the city, therefore, has rather the aspect of a watering-place [for horses] than the metropolis of a great nation. The members of Congress generally live together in small boardinghouses, which from all I saw of them, are shabby and uncomfortable.

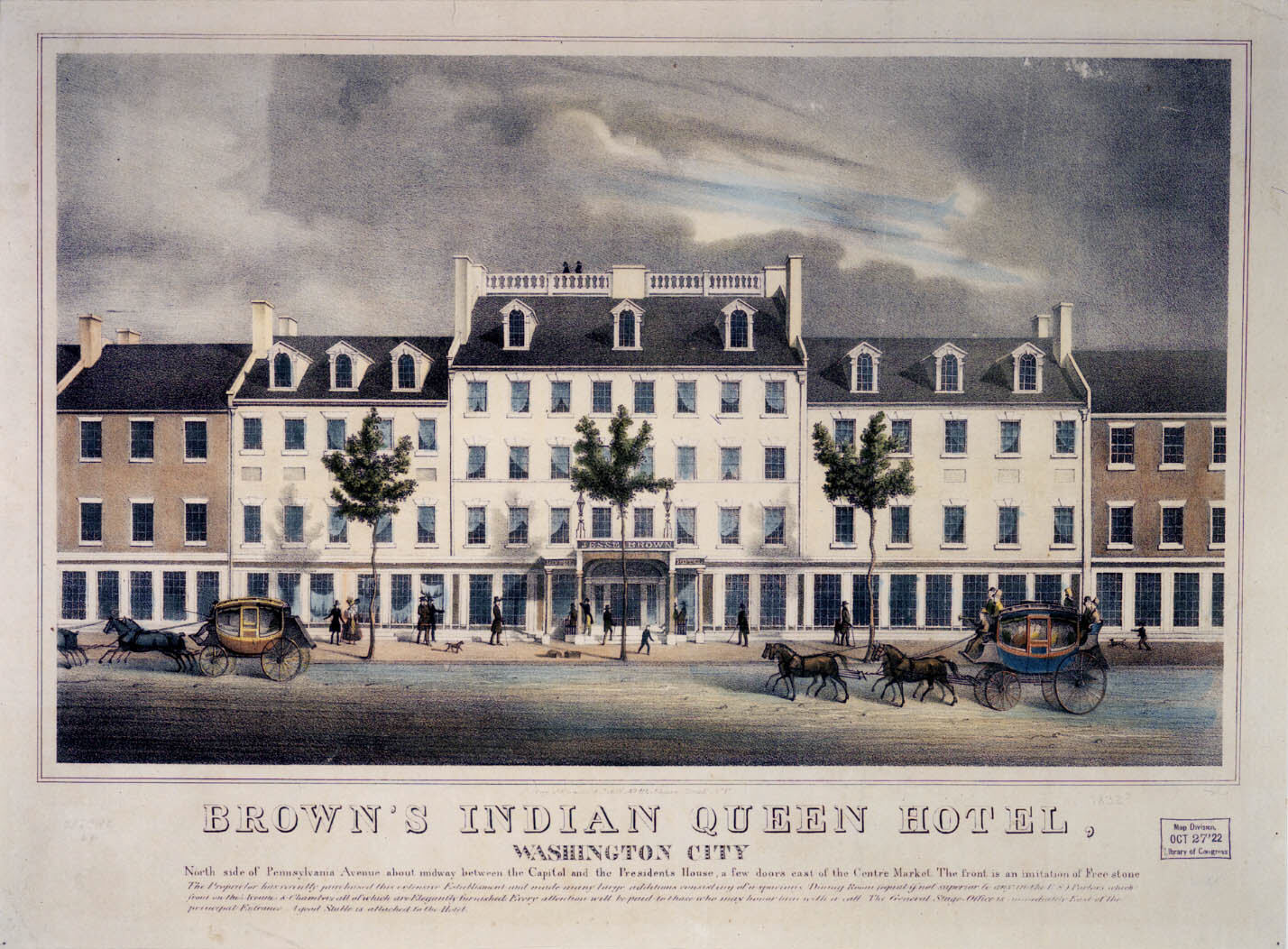

When John Marshall became Chief Justice in 1801, he encouraged all of the Justices to live together at one location. Over the years, they took up residence at Brown’s Indian Queen Boarding House, Stelle’s Hotel, and Tench Ringgold’s House (now called the Dacor Bacon House). This decision fostered unity and created a brotherhood among the Justices. In fact, of the 1,129 opinions handed down by the Marshall Court, 1,042 were unanimous partly due to the camaraderie the Justices built in Washington.

These temporary lodgings were especially important as Congress did not assign a permanent location for the Court to hold sessions. For the first decade, the business of the nation’s highest court took place in various locations including a shared space in Philadelphia’s City Hall. When the Capitol Building was constructed, Congress again did not designate a space for the Court. Congress lent the Marshall Court (and lower federal courts) a small committee room to conduct its business. Lacking an adjacent room for preparation, the Justices had to put their robes on as they entered the room.With no permanent location to call their own, the boarding houses became their unofficial headquarters–providing a semi-private space for the Justices to conduct their conferences and review cases. Often over meals, Chief Justice Marshall was able to use his intellect and charm to influence his fellow Justices in their decision making. Marshall even arranged for cases of fortified wine, known as Madeira, to be shipped to Washington each term in bottles labeled “The Supreme Court.” Without family, the Justices developed a strong bond that allowed for efficient, unified resolutions of cases. Justice Joseph Story observed to a friend:

Indeed we are united as one, with a mutual esteem which makes even the labors of Jurisprudence light…The mode of arguing cases in the Supreme Court is excessively…tedious…We moot every question as we proceed, and my familiar conferences at our lodgings often come to very quick, and, I trust, a very accurate opinion, in a few hours.

In those early years it was not uncommon for opinions to be handed down within a week of the argument. The boarding houses were occasionally used for that as well. Chief Justice Marshall handed down the landmark Marbury v. Madison opinion from the steps of Stelle’s Hotel.

While the Justices certainly missed their family and the comforts of home, they enjoyed the collaborative atmosphere encouraged by Marshall. Justice Story wrote to his wife, Sarah:

It is certainly true, that the Justices here live with perfect harmony…our social hours when undisturbed with the labors of law, are passed in [happy] and frank conversation, which at once enlivens and instructs.

In 1810, the Court was finally given its own elegant (but windowless) chamber in the basement Capitol Building. But during the War of 1812, the British army burned the Capitol forcing the federal government, including the Supreme Court, into temporary meeting places for several years. Despite this instability, the Court continued to hear cases and depend on boarding house dining rooms as venues for their conference deliberations in the early decades of the Supreme Court.

As the capital city developed, more government representatives began to bring their families to Washington and the social atmosphere became more attractive. In the 1830s, the practice of all of the Justices living together in a boarding house disappeared when some men chose to rent personal or family quarters rather than individual rooms while others lived with members of Congress. The brotherhood of the early Marshall Court years, however, established lasting precedents and laid a firm foundation for the federal judiciary. By establishing cohesion amongst the seven Justices in Court decisions, members of the Court were able to build credibility and consistency in the law across the growing country. This effort helped the judicial branch as it developed its co-equal status with the other two branches of government.

Discussion Questions

- Why were boarding houses and hotels necessary in Washington, DC, during the 18th and 19th centuries?

- How did living at boarding houses impact the Marshall Court?

- Do you think it’s significant that Congress did not designate a space for the Supreme Court? Explain.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and history professor Rachel A. Shelden for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Clare Cushman, Courtwatchers: Eyewitness Accounts in Supreme Court History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2011).

Feature Image: Brown’s Indian Queen Hotel. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Rachel Shelden, Washington Brotherhood: Politics, Social Life, and the Coming of the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press (2013).