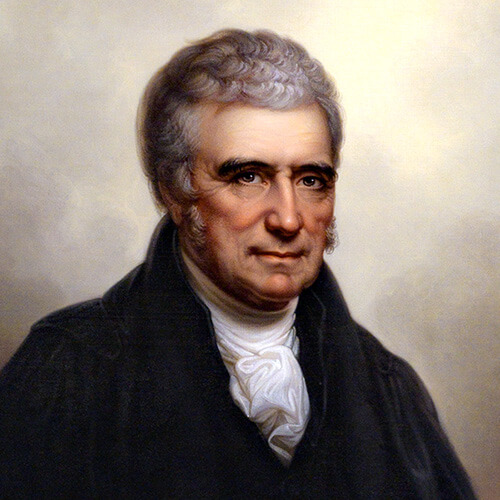

John Marshall

Life Story: 1755-1835

The soldier, attorney, and American statesman who became the longest serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

Background

John Marshall was born near Germantown, Virginia on September 24, 1755. His father, Thomas Marshall, was a land-owner and farmer who served in the local government. The Marshall farm, Oak Hill, had twenty-two enslaved people. Mary Randolph Marshall, John’s mother, was the daughter of a minister and relative of the Randolph Family which linked John to future president, Thomas Jefferson. John was one of 14 children. His childhood on the rural Virginia frontier was challenging and his family often struggled financially. As a boy, John went to school for one year at the Westmoreland Country Academy with future president James Monroe.

When the Revolutionary War began, John left home to serve in the Virginia Continental Regiment, eventually achieving the rank of captain. Future President General George Washington admired John and appointed him Judge Advocate General of the Continental Army before he had any legal training. His wartime experiences shaped his beliefs, especially the importance of a central government including a strong military. When his service ended in 1780, John began his legal studies at the College of William and Mary with fellow future Justice Bushrod Washington. Three years later, he passed the bar and moved to Richmond to be closer to his future wife, Mary “Polly” Willis Amber, the daughter of the Virginia state treasurer. The two married and had 10 children together, 6 of whom lived to adulthood.

John’s law practice grew steadily and he became a sought-after attorney. He also served on the Virginia delegation that ratified the new Constitution in 1788 after the failure of the Articles of Confederation. After his service, he continued to represent Virginians in court. His renowned legal skills were in high demand and he was selected to be the lead attorney in the landmark case Ware v. Hylton (1796) before the Supreme Court of the United States. Though the Court ruled against him and his client, and overruled a Virginia law under the supremacy clause, the case increased John’s fame. His reputation helped his political career. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and the Virginia Governor’s Council of State. Throughout his life, John supplemented his legal and government incomes by purchasing and selling large tracts of land. He also bought enslaved people to work in his home and on his land. By the 1830s, he and his five sons had acquired several large farms; approximately 250 enslaved persons worked on their plantations.

A popular and accomplished professional, John was nominated for various positions by the president, which he often refused. When President John Adams asked for his help on a diplomatic mission to France, however, he accepted. The mission became known as the XYZ Affair and news of his service further contributed to his fame. At the encouragement of former president George Washington, John decided to run for one of the Virginia seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected and began his service in December 1799. As a Congressman, John was well-known for his participation in floor debates and President Adams took notice, nominating John to serve in his Cabinet as Secretary of State. John excelled at that job too, often handling the daily administration of the federal government when the president was out of town.

The Supreme Court

When Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth resigned, President Adams decided to nominate John to the Supreme Court. John was confirmed on January 27, 1801. A few weeks later, his cousin and political adversary, Thomas Jefferson, was sworn in as the third President of the United States. A Democratic-Republican, President Jefferson’s election marked the first peaceful transition between political parties for the young United States. Knowing his term would soon be over, President Adams made a series of “midnight” appointments for various judicial positions after the Federalist-dominated Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801. Still serving as Secretary of State, John was supposed to notify each of the appointees of their commissions but his staff did not reach everyone. This oversight led to a lawsuit and a conflict between the three branches of government that resulted in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison (1803). As Chief Justice, John wrote a masterful opinion that affirmed the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review, which established that the fledgling Supreme Court had the authority to interpret the words in the Constitution. As such, the Court has the authority to decide whether an act of Slot Congress or an order by the President violates the Constitution. His Marbury v. Madison opinion also reinforced “rule of law” by saying that no one is above the law, including the President and the Cabinet.

John’s 34 years of service on the Supreme Court are termed “the Marshall Court.” During that time his influence varied. Early on, John was able to mold a unified court due to his likable personality and sharp legal mind. He invited the other Justices to live together in local boarding houses during the Court term, creating a brotherhood-like bond and providing John the chance to share his thoughts and opinions about cases less formally. He was also supported by longtime friend and colleague Bushrod Washington. Utilizing his influence, John persuaded his colleagues to issue unanimous “Opinions of the Court” and speak with one, powerful voice. In 1812, Joseph Story of Boston was confirmed as a Justice and became an intellectual ally and friend. Like Bushrod, Joseph embraced John’s vision of a strong federal government. At this point, John had so firmly established the power of the Supreme Court that when new justices wrote dissents it was not weakened.

The 1819-1822 era is considered the golden age of the Marshall Court and John’s tenure. During that time, the United States went through a period of economic growth and westward expansion. Naturally, significant cases arose and with them came some of Marshall’s greatest decisions. McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), Cohens v. Virginia (1821), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824, initially presented in 1821) were argued before the court during this time. Under John’s leadership, the Supreme Court asserted the power of the federal judiciary and protected the supremacy of the Constitution and federal law.

During the final third of the Marshall Court, the unity the Court once knew was threatened. Washington was becoming more populated so some of the Justices brought their families to town or chose to live by themselves. The bond the Justices had built by boarding together suffered and John lost some of his influence. More threatening to unanimity were the four new Justices appointed by President Andrew Jackson who favored states’ rights. The Chief Justice lost his dominance and even delivered his only dissenting opinion in Ogden v. Saunders (1827). President Jackson then challenged the Court’s authority over Native American treaty rights in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832) when he refused to implement the Court’s opinion. John’s devotion to a strong federal government was losing to President Jackson’s vision of increasing states’ rights.

This final period was also marked by personal struggles for John. He survived surgery in 1831, but his beloved wife, Polly, who had been an invalid for most of their marriage, passed away later that year. A few years later he was plagued with more health issues and died on July 6, 1835, a few months shy of his eightieth birthday.

Legacy

During his 34 years as Chief Justice, the Court issued 1,129 decisions of which 1,042 were unanimous due to the cohesion John encouraged amongst his colleagues. The longest-serving Chief Justice in U.S. history, John is greatly admired for his allegiance to the United States. He is revered for expertly guiding legal institutions to protect the United States as it grew and developed into a successful republic. Thanks to John’s leadership and dedication, the judiciary became a powerful, independent, and co-equal branch of government, with the Supreme Court as the final authority of Constitutional questions.

Discussion Questions

- How did John’s life experiences prepare him to serve as the Chief Justice of the United States?

- How did John influence the Supreme Court’s practices and procedures?

- What do you think is John’s most significant accomplishment?

- How did John’s service as Chief Justice impact the federal judiciary?

- How would you summarize the legacy of Chief Justice John Marshall?

Extension Activities

-

Make a list of 5 qualities you think a person must have in order to be considered a leader. Does John Marshall reflect those qualities? Would you consider him to be a great leader?

-

Compare and contrast: Using outside resources, compare and contrast the leadership styles of George Washington and John Marshall. How did each figure shape his respective branch of government?

-

Using the resources provided for Marbury v. Madison at LandmarkCases.org, consider the following question: Do you believe the judicial branch could have emerged as a co-equal branch of government without John’s leadership? Explain using specific examples.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and author Professor G. Edward White for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Charles F. Hobson, Review Essay: Paul Finkelman, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2018) (Washington, D.C., Journal of Supreme Court History, 2018 Vol. 43 No. 3).

Clare Cushman, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies 1789-2021, (Sage Publications, Inc., 2013) pp. 53-57.

Feature Image: Chief Justice John Marshall. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Joel Richard Paul, Without Precedent: Chief Justice John Marshall and His Times (Riverhead Books, 2018).

John Marshall Center for Constitutional History and Civics, “John Marshall and Slavery,” https://johnmarshallcenter.org/john-marshall-and-slavery/

Paul Finkelman, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2018).