Joseph P. Bradley

Life Story: 1813-1892

The Supreme Court Justice who held the deciding vote on the Electoral Commission for the presidential election of 1876.

Background

Joseph P. Bradley was born in the small farming town of Berne, New York on March 14, 1813. He added the middle initial “P” later in life—possibly in honor of his father, Philo—but it did not stand for anything. Joseph was the first of 12 children born to Philo and Mercy Gardner Bradley, all of whom worked on their family farm. The work was extremely demanding and required an all-hands-on deck approach. As a result, Joseph and his siblings rarely made it to the local school. He took responsibility for the family’s education and started teaching the younger children at home when he was 15. Resources were scarce, but Joseph strongly believed in the value of education. Once, he walked five miles to borrow an algebra book from an uncle.

When Joseph turned 18, he left Berne for New York City to pursue a college education. He travelled 30 miles east to Albany, the state’s capital, where he purchased a boat ticket south to Manhattan. He planned to work as a store clerk until he saved enough money for school. However, freezing water temperatures derailed his plans. The boat to New York left a few minutes early, and the ice delayed any other boat travel for months. Before returning to Berne, he used the unexpected time in the state’s capital to observe the legislature, a choice that altered the course of his life. The experience inspired him to study law. With the help of a mentor at home, he enrolled at Rutgers College in 1833.

Joseph was a serious student who excelled at languages and mathematics. He graduated in two years. In 1836 he began pursuing rigorous self-directed legal studies. In that era, law school was not required to become an attorney. Rather, aspiring lawyers like Joseph completed apprenticeships where they independently studied case law and legal theories. After finishing the apprenticeship, Joseph was admitted to the New Jersey bar on November 14, 1839.

Career

Joseph established himself as a prominent corporate law attorney in Newark, New Jersey. For 30 years, he specialized in corporate, patent, and commercial law. His most important client was New Jersey’s first railroad, the Camden and Amboy (C&A). The C&A was part of a rapidly growing network of rail travel that connected previously isolated regions of the country. Railroads companies used aggressive business tactics, like hostile mergers, to establish monopolies that allowed them to dominate regions and set high prices. These unprecedented practices faced frequent legal challenges from farmers and small manufacturers who depended on railroads to ship their products. Defending railroads was a lucrative practice for corporate attorneys and Joseph became wealthy and socially prominent. In 1844, he married Mary Hornblower, the daughter of the Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. They had seven children, four of whom lived to adulthood.

Outside of his private law practice, Joseph drew on his advanced mathematical skill to serve as an actuary for 12 years at a Newark insurance firm. Additionally, he had one unsuccessful Congressional campaign as a Republican in 1862, in the midst of the Civil War.

The Supreme Court

Despite having no judicial experience, Joseph openly sought appointment to the Supreme Court. His prominence as a railroad attorney caught the attention of President Ulysses S. Grant when two vacancies opened on the Supreme Court bench. Though Joseph was not the president’s first choice for either opening, one nominee fell ill and died, and the other failed to be confirmed by the Senate. Moving on to his third choice, President Grant nominated Joseph in February of 1870. The Senate confirmed his appointment with a 46-9 vote. Justice Bradley served on the Court for 22 years, authoring opinions that impacted the course of commerce law and civil rights.

Commerce

During the late 1800s, the Justices frequently reviewed cases involving the federal government’s power to regulate commerce. The growth of big businesses, including railroads, raised questions about how much the government could intervene in private business practices. Despite Justice Bradley’s years defending railroads as a lawyer, he denounced them as “absolute monopolies of public service.” Additionally, In Munn v. Illinois (1877), he worked closely with Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite, whose majority opinion affirmed the state’s power to set price ceilings for different goods and services.

Civil Rights

After the Civil War, the Supreme Court heard a variety of legal challenges under the new Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Bradley was a critical member of the Supreme Court bench that first interpreted how this amendment applies to the law. In the Slaughter House Cases (1873), brought by Louisiana livestock butchers, Justice Bradley dissented. The Court’s majority held that the privileges and immunities clause was only intended to apply to formerly enslaved African Americans and thus did not protect the butchers, who argued that the state was unreasonably interfering with their slaughterhouse operations. Justice Bradley argued instead that practicing one’s chosen profession is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. He did not, however, extend this reasoning to women in the workplace. In Bradwell v. Illinois (1873), the Court held that the state of Illinois was not obligated to admit aspiring (and qualified) lawyer Myra Bradwell to the bar. Justice Bradley’s concurring opinion reflected a stance on gender typical of the time. To him, the “timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.”

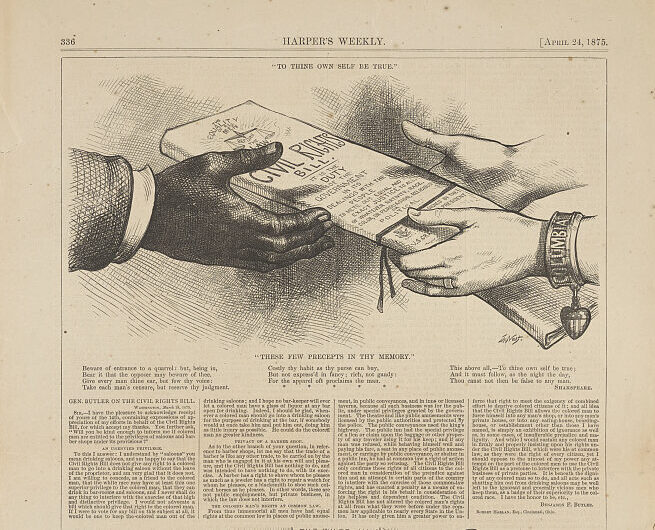

Prevailing stereotypes also infused Justice Bradley’s majority opinion for the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. The decision invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibited racial discrimination in public accommodations (but not schools). He wrote for the Court that “when a man has emerged from slavery…there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws.” Congress did not enact a new civil rights law prohibiting racial discrimination until 1964.

Election of 1876 Commission

In 1877, Congress created an electoral commission to decide the outcome of the disputed 1876 presidential election in which both candidates received the same number of electoral votes. It appointed 10 members of Congress (5 Democrats and 5 Republicans) and 4 Justices (appointed evenly by presidents from both parties). To avoid a potential deadlock, and a split along partisan lines, the commission needed a 15th member. Justice Bradley agreed to serve- knowing that he would be choosing the next president and that his vote would be criticized by half the country. The decision weighed heavily on Joseph. He confided in his diary that he “wrote and rewrote the arguments and considerations on both sides as they occur to me, sometimes being included to one view of the subject, and sometimes to the other.” In the end, Justice Bradley voted with the Republicans on all issues, resulting in the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Circuit Riding

Like all Supreme Court justices during the 1800s, Joseph also served as a circuit court judge. He rode circuit for four months each year, hearing cases in cities and towns in his assigned region. For most of his tenure, he sat on the Fifth Circuit, which included Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.

Legacy

Joseph P. Bradley died on January 22, 1892 in Washington, D.C. at age 78. He was in his 21st year on the Court. Joseph was an intellectual and eccentric man. His personal library contained over 16,000 books, and in addition to his law expertise he studied math, philosophy, and science. His judicial influence on commercial regulation and civil rights, along with his deciding vote in the election of 1876, shaped United States law for decades to come.

Discussion Questions

- How did Joseph Bradley respond differently to the Slaughter House Cases and Bradwell v. Illinois?

- Why was Joseph’s role on the Electoral Commission significant?

- Why was the Supreme Court hearing so many legal challenges to the Fourteenth Amendment while Justice Bradley was on the bench?

Sources

Special thanks to scholars and law professors Grier Stephenson and Paul Kens for their review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Official portrait of Justice Joseph P. Bradley. Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872)

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

Cushman, Clare, ed. “Joseph Story: 1813–1892.” The Supreme Court Justices of the United States: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2013.

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1872)

Stephenson Jr., Donald Grier. The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacies. ABC-CLIO, 2003.

The Supreme Court and the Election of 1876. The Supreme Court Historical Society. August 17, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJaydek_96w.

Waldrep, Christopher. “Joseph P. Bradley’s Journey: The Meaning of Privileges and Immunities.” Journal of Supreme Court History 34, no. 2 (2009). 149-163.