United States v. Cruikshank (1875)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that limited the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment and weakened enforcement of federal Reconstruction policies.

Background

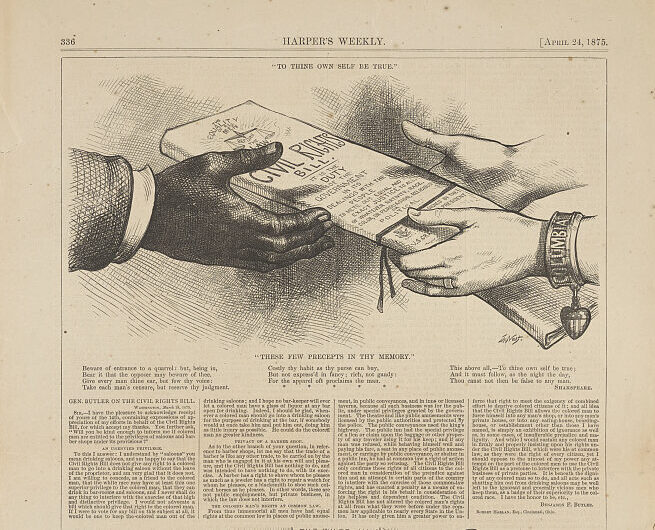

In the years following the Civil War, the Republican-controlled federal government passed Reconstruction Amendments and enforcement legislation aimed at expanding and protecting the rights of formerly enslaved people. The Thirteenth Amendment formally abolished slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited states from denying the “equal protection of the law,” and the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited states from denying the vote based on race. For a time, these amendments successfully enfranchised Black voters. Between 1869 and 1901, voters elected 22 Black men to Congress, while many others served in positions in state and local governments. In response to the new Amendments and the elected Black officials, extreme violence erupted across the South. White supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan attacked Black Americans and white Republicans who attempted to exercise their right to vote. The federal government temporarily curbed the Klan’s violence with a series of Enforcement Acts. The acts, passed in 1870 and 1871:

- made it a federal crime for groups to conspire to prevent citizens from exercising constitutional rights;

- increased federal government power over both national and local elections; and

- expanded the power of the President to combat violent groups who conspired to deny equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment or the right to vote under the Fifteenth Amendment.

Despite the progress made with these acts, the Panic of 1873 triggered a nationwide depression and made it difficult for the federal government to enforce its Reconstruction policies. Many citizens blamed Republicans in government for the economic downturn and elected a Democratic majority to the House of Representatives in 1874. Now in control of the budget, Democrats, who had opposed Reconstruction legislation, ended federal funding for the Enforcement Acts.

Facts

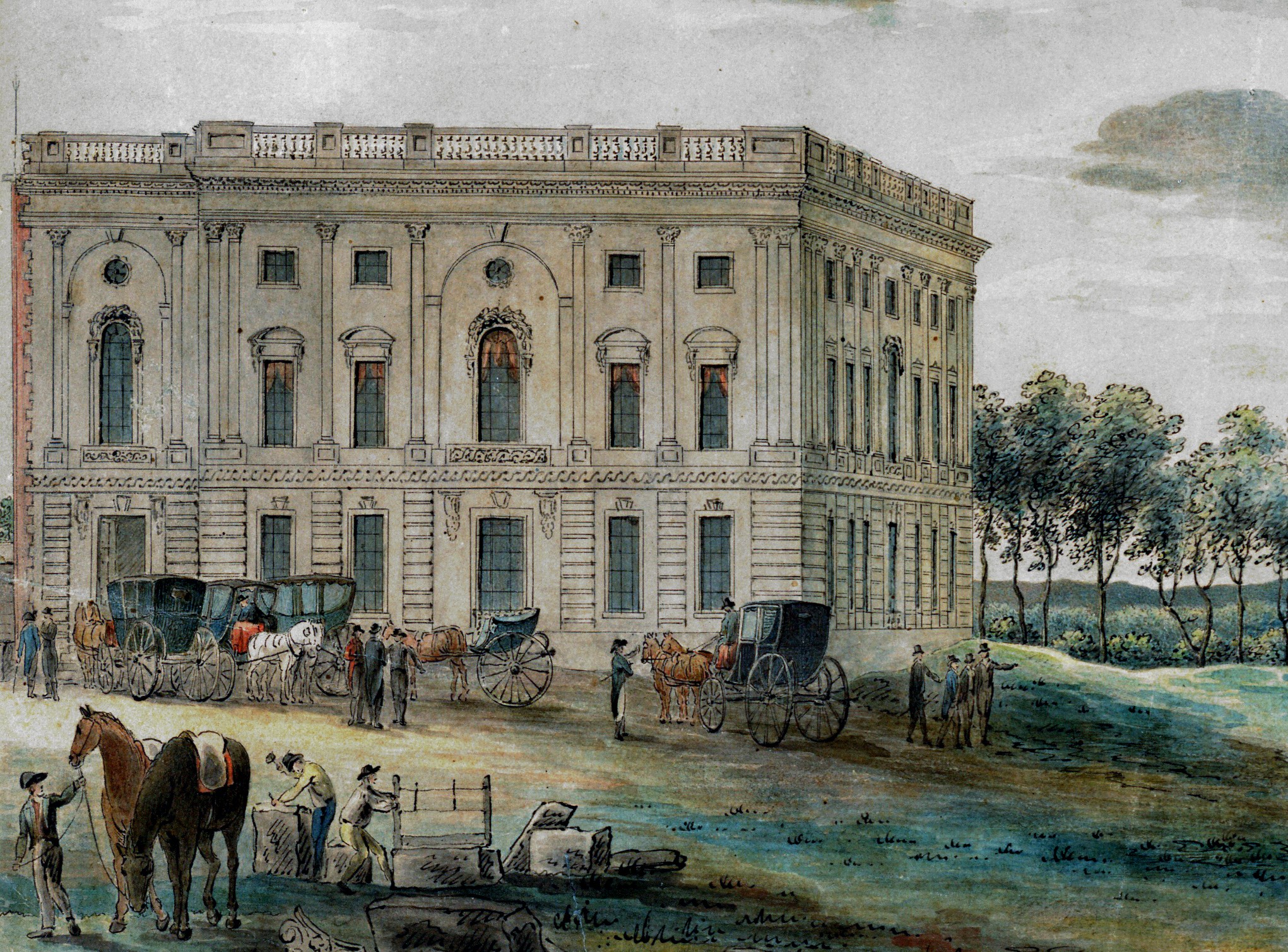

In the 1872 Louisiana state election, Republicans—the party that supported African American rights and Reconstruction—marginally retained power. Black men, who narrowly outnumbered white voters, helped elect Governor William Pitt Kellogg and Republican representatives at both the state and local levels. Democrats disputed the election results and swore in their own leaders, leading to two competing governments and chaos across Louisiana. The Klan and other white paramilitary groups rampaged across the countryside, randomly and violently killing innocent African Americans.

As these terrorists stormed through Grant Parish in central Louisiana, hundreds of Black citizens sought refuge in the Courthouse in the town of Colfax. By April 13, 1873, several weeks after the occupation began, roughly 150 to 300 armed white men surrounded the Colfax Courthouse. Fighting ensued. By the afternoon the Black citizens surrendered. As they began leaving the building unarmed, the white mob outside started shooting. Reports vary, but it is estimated that between 62 and 81 Black people were killed. About 40 Black men were also taken prisoner and later executed.

The U.S. Attorney for Louisiana, James Beckwith, federally indicted 97 members of the mob, all of whom were white men. In the end, only nine defendants faced charges. Many of the accused either fled the area or were protected by people in positions of power. Each of the nine defendants faced 32 counts under the Enforcement Act of 1870. The first 16 counts were based on Section 6 of the act which made it a federal crime for “two or more persons to band or conspire together” to deprive someone else of “the free exercise and enjoyment of any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the constitution or laws of the United States.” The defendants were charged with infringing on the rights to assemble, to bear arms, to have equal protection, and to vote. The charges did not specify the racial motivation behind the massacre, however, which proved to be detrimental to the prosecution of the crime.

At the circuit level, two jury trials took place. Circuit Judge William B. Woods declared a mistrial in the first trial after the jury could not agree on a verdict. During the second trial, Judge Woods was joined by Supreme Court Associate Justice Joseph P. Bradley while he rode circuit. On June 10, 1874, the court found five of the defendants not guilty on all charges. William Cruikshank, John P. Hadnot, and William B. Irwin were found guilty on the first 16 charges relating to Section 6 of the Enforcement Act, but not guilty of murder.

Cruikshank’s attorney, R.H. Marr attempted to secure a new trial for the guilty defendants alleging a lack of federal jurisdiction. Woods voted to uphold the indictments, rejecting the new trial. Bradley disagreed, however, and presented an original rationale known as the state action doctrine. He explained the federal government could only intervene to protect natural rights if a state first violated them. Additionally, Beckwith’s indictments under the Amendments were invalid because they did not allege a racial motive, which was necessary to bring the crimes under federal power. Justice Bradley’s opinion at the circuit level was the first elaboration of state action doctrine. Motivated by the justice’s reasoning, Cruikshank’s attorney appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States

Issues

- Do the First Amendment’s right to assemble and Second Amendment right to bear arms apply to the states or private citizens, or are they only intended to restrict the federal government?

- Do the Fourteenth Amendment rights of due process and equal protection apply to the actions of individuals, or only to state action?

Summary

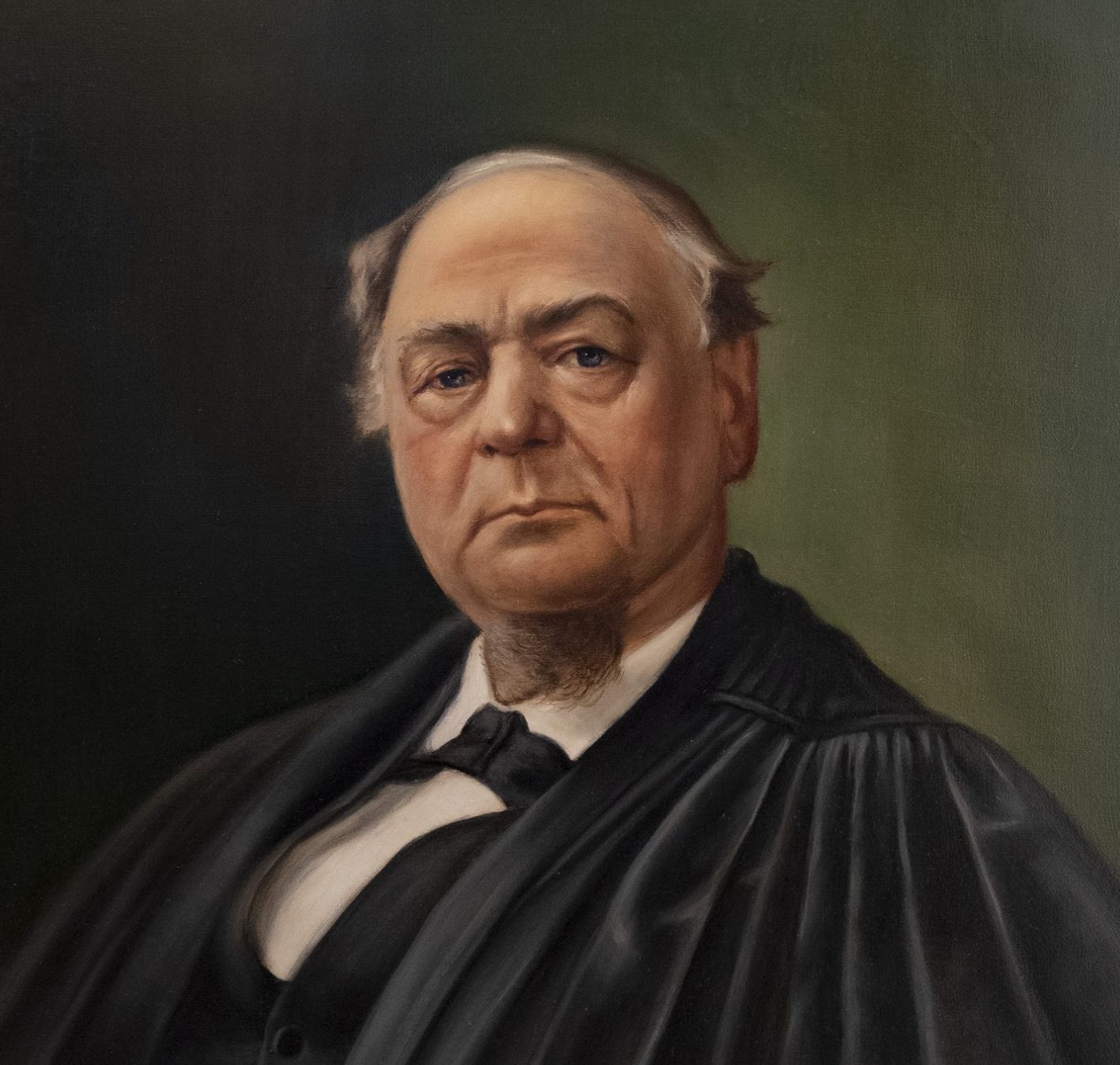

On March 27, 1876, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the convictions of Cruikshank, Hadnot, and Irwin. Justice Bradley’s circuit opinion, which emphasized the state action doctrine, significantly influenced the Court’s decision. Chief Justice Morrison Waite, citing Barron v. Baltimore (1833), wrote for the Court that the defendants’ acts of fraud and violence were state offenses, not federal offenses. He continued on to say that the Constitution was meant to protect citizens from actions by the government, not private individuals. Therefore, neither the First Amendment, Second Amendment, nor the Fourteenth Amendment applied to this case. The Court also held that the indictments against Cruikshank and the other defendants were too vague. According to Justice Waite, the counts listed were so “defective” that they deprived the defendants of due process. The Court suspected that “race was the cause of the hostility,” but made no judgement on it since it wasn’t included in the original indictments.

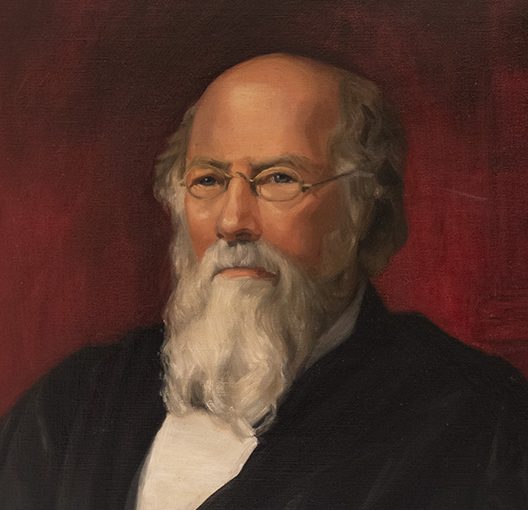

In his concurring opinion, Justice Nathan Clifford agreed that the indictments were too vague. He concluded that because the accused could not organize an effective defense, it was invalid. However, Justice Clifford disagreed with the majority about its interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. He believed it did give the federal government the power to prosecute individuals who limited the rights of others.

Precedent Set

Justice Bradley’s circuit court opinion elaborating the state action doctrine became the basis of the Cruikshank decision. In general, the Court’s decision limited the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights, clarifying they prohibit violations of rights carried out by the federal government, but did not carry the same power to prohibit state and private actions. The opinion emphasized the “no state” language of the Fourteenth Amendment, leaving most crimes to be handled by state courts. Federal government intervention would only happen in cases involving state legislatures or officials. The question of whether “state action” included a state’s systematic refusal to punish racial violence was left unanswered.

Additional Context

The event in Colfax is believed to be the “bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction Era.” Even in the face of violence, though, Black men in Colfax and around the United States continued to exercise their right to vote. In 1884, the Supreme Court held that the Congress had the right to punish individuals who interfered with federal elections and sent Klansmen to jail (Ex parte Yarbrough). The political situation changed in the 1890s, as new state constitutions were enacted across the South that disenfranchised Blacks (and poor whites) by using literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses. The expanded suffrage of the Reconstruction era ended and efforts to protect Black voting rights were not federally recognized until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Decision

The Supreme Court unanimously overturned the convictions of Cruikshank, Hadnot, and Irwin.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Waite

-

Clifford

-

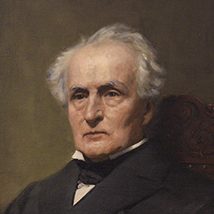

Miller

-

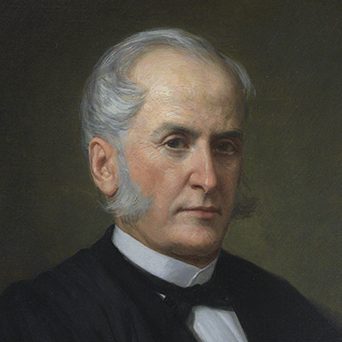

Swayne

-

Davis

-

Field

-

Bradley

-

Strong

-

Hunt

-

Majority Opinion

Morrison R. WaiteRead More CloseThe conclusion is irresistible that these counts are too vague and general. They lack the certainty and precision required by the established rules of criminal pleading. It follows that they are not good and sufficient in law. They are so defective that no judgment of conviction should be pronounced upon them.

-

Concurring Opinion

Nathan CliffordRead More CloseI concur that the judgment in this case should be arrested, but for reasons quite different from those given by the court. Power is vested in Congress to enforce by appropriate legislation the prohibition contained in the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, and the fifth section of the Enforcement Act provides to the effect that persons who prevent, hinder, control, or intimidate, or who attempt to prevent, hinder, control, or intimidate, any person to whom the right of suffrage is secured or guaranteed by that amendment, from exercising or in exercising such right by means of bribery or threats; of depriving such person of employment or occupation; or of ejecting such person from rented house, lands, or other property; or by threats of refusing to renew leases or contracts for labor; or by threats of violence to himself or family — such person so offending shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and, on conviction thereof, shall be fined or imprisoned, or both, as therein provided.

Discussion Questions

- What was the purpose of the Enforcement Acts that were passed in the early 1870s?

- What factors led to the decline in the effectiveness of Reconstruction legislation?

- What specific systemic challenges prevented the full realization of voting rights for African Americans during this time period?

- The charges did not specify a racial motivation behind the massacre. How did this impact the Court’s decision?

- Although this case was not prosecuted on the basis of race, explain how the outcome impacted the rights of Black Americans.

- How did the Cruikshank decision affect the original goals of the Enforcement Acts and Reconstruction?

Sources

Special thanks to scholars and law professors Pamela Brandwein and Michael Ross for their review, feedback, and additional information.

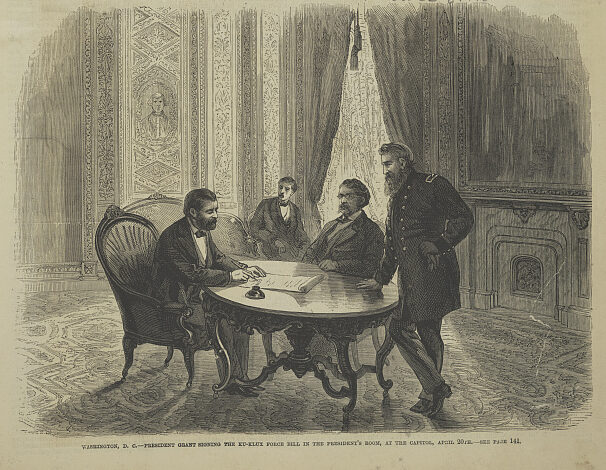

Featured image: Washington, D.C. – President Grant signing the Ku-Klux Force Bill in the President’s room with Secretary Robeson and Gen. Porter, at the Capitol, April 20. , 1871. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002716005/.

Benedict, Michael Les. “Preserving Federalism: Reconstruction and the Waite Court,” Supreme Court Review (1978): 39-79.

Brandwein, Pamela. “A Lost Jurisprudence of the Reconstruction Amendments.” Journal of Supreme Court History 41, no. 3 (2016).

“Civil Rights Act of 1870.” Federal Judicial Center. https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/civil-rights-act-1870.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 2015.

Kousser, J. Morgan. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910. Yale University Press, 1974.

Goldman, Robert. Reconstruction and Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese and Cruikshank. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Lane, Charles. The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, Henry Holt, 2008.

“United States v. Reese.” Oyez. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/92us214.Wang, Xi. The Trial of Democracy: Black Suffrage and Northern Republicans 1860-1910 University of Georgia Press, 1997.