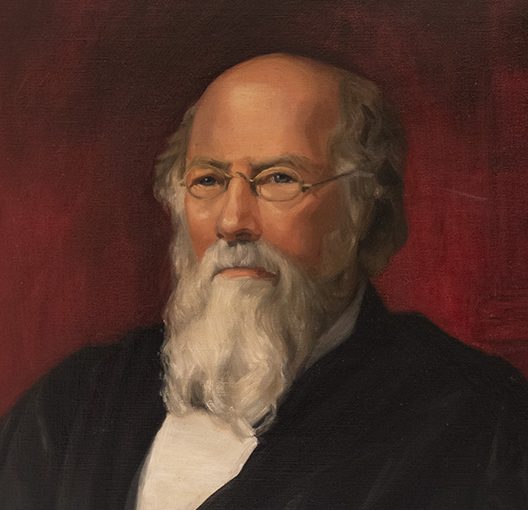

Samuel Freeman Miller

Life Story: 1816-1890

The frontier physician and self-taught lawyer who helped shape the interpretation of the Reconstruction Amendments as an Associate Justice on the post-Civil War Supreme Court.

Background

Samuel Freeman Miller was born in Richmond, Kentucky on April 5, 1816 to a poor farming family. Both of his parents moved to Kentucky by way of the East Coast—his father from Pennsylvania and his mother from North Carolina. The oldest of 10 children, Samuel took on extra responsibilities at home and helped raise his younger siblings. Though built for a life on the farm—he stood six feet tall and weighed over 200 pounds—Samuel was not fond of the physical labor that came with farming. He cherished his time attending school at Richmond Academy, and his teachers called him an “excellent” student. His family’s financial situation, however, forced him out of school at age 14, and he found work as a pharmacist’s assistant. Samuel’s time working at the pharmacy inspired him to study medicine, and in 1836, he enrolled in medical school at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.

While in medical school, one of Samuel’s professors advised students to “be judicious in the choice of home, and there plant yourselves.” Staying in one place permanently allowed physicians to build trust and stability among patients. Samuel took this advice to heart and settled in Barbourville, Kentucky. As the first doctor in the frontier town, Samuel quickly built a successful practice. By the 1840s, however, he became disillusioned with his career. Working as a rural doctor was demanding: it required long days travelling alone, carrying a heavy medicine bag, with often discouraging results. Samuel felt he lost more patients than he helped, especially during Barbourville’s frequent cholera outbreaks. When he sought a career change, law was a natural fit. Samuel and a local attorney shared office space, which allowed him to study law each day after visiting with patients. Additionally, he married into a family of lawyers. In 1842, Samuel met his wife, Lucy Ballinger, the daughter of two of the town’s founding settlers. All of the men in Lucy’s family—her father, grandfather, and brothers—practiced law, providing Samuel with a personal connection to the legal world. In 1847, he was admitted to the Kentucky Bar and began formally practicing law.

Outside of work, Samuel founded the Barbourville Debate Society in 1837. Barbourville had no newspaper or theater, so the society became a place where locals could discuss important issues of the day and hear news from around the United States. Samuel remembered the Debating Society meetings as some of the first times he felt intellectually challenged, saying that he heard “as able discussions in the debating society…as at any other time or place, not even excepting the Supreme Court of the United States.” Many of these conversations reflected the larger debates happening in Kentucky, especially regarding slavery’s fate. Though Samuel enslaved three people as servants in his home, he argued in favor of a gradual end to slavery in Kentucky. He embraced the ideas of an influential abolitionist named Cassius Clay, who advocated for a state-wide plan that would free the children of slaves when they became adults. When the Kentucky legislature rejected Clay’s proposal, Samuel and Lucy abandoned Barboursville for the free state of Iowa and freed their slaves. Samuel then helped to found the Iowa Republican Party, which was committed to preventing slavery’s expansion in the West.

The Miller family’s move to Iowa also had economic motivations. As Barboursville’s economy declined, the booming frontier town of Keokuk, Iowa held significant promise. When Samuel and Lucy settled there in 1850, residents expected it to grow into the next Chicago. Opportunity in Keokuk seemed abundant for Samuel. The developing town needed attorneys, so there was plenty of business for the new lawyer. Over the next 12 years, he became the town’s most prominent attorney, and handled everything from divorces and bankruptcies to criminal cases. Samuel also invested in real estate, hoping to benefit from the town’s boom. Tragedy, however, would strike both the Miller family and Keokuk. By 1854, Samuel’s wife and his law partner Lewis Reeves died, leaving Samuel to parent his three young daughters while managing the law firm and the Reeves estate. Overwhelmed with responsibility, Samuel sent his girls to live temporarily with an uncle in Texas. He brought his daughters back home after he remarried to Reeves’ widow, Eliza, in 1856. The couple later had two children of their own. Keokuk’s economy, meanwhile, was ravaged by the Panic of 1857, which destroyed any possibility of the town becoming one of the nation’s great cities. The crash and the town’s steep decline left a lasting impact on both Samuel’s wallet and world outlook. His real estate holdings lost significant value, and he became resentful towards the bond holders and industrial capitalists to whom the town became indebted.

The Supreme Court

After President Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, South Carolina seceded from the United States and the Civil War began. Associate Justice John Campbell, a supporter of the Confederacy, promptly resigned from the Supreme Court. The resignation, along with the deaths of Justices Peter V. Daniel and John McClean, gave Lincoln the rare opportunity to appoint three justices in one year. After Congress reorganized the Ninth Circuit in 1862 to include Iowa, state elected officials campaigned for Samuel Miller to fill one of the vacancies. Congressional members joined in their campaign and sent letters to the president. Though Lincoln never met him, the broad support from the Republican Congress indicated that Samuel aligned with his political views and would back his wartime agenda. President Lincoln submitted Samuel’s name to the Senate on July 16, 1862, which confirmed the nomination within 30 minutes, an unusually swift confirmation. On July 21, Samuel Miller became the first Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from a state west of the Mississippi River. Eliza and the children stayed in Keokuk while Samuel moved to Washington, D.C. He returned every summer until financial troubles forced the Millers to sell their home and permanently relocate to the nation’s capital. Unlike most other Justices, Miller had no prior judicial experience, so he read through every Supreme Court decision since its founding 73 years earlier. By the time he died in 1890, he had asserted himself as a dominant force on the Court.

The Civil War

At the beginning of Justice Miller’s tenure, the Court heard several challenges to Lincoln’s actions during the Civil War. For example, in April 1861, the president ordered a blockade of all Southern ports to prevent the Confederacy from receiving military supplies—three months before Congress authorized a declaration of war. The U.S. Navy captured several ships bound for the Confederacy, and these merchants challenged the blockade in federal court. According to the merchants, Lincoln did not have the authority to order a blockade without a state of war. In the Prize Cases (1863), Samuel joined the 5-4 majority opinion in upholding Lincoln’s blockade measures.

Rights

After the Civil War, the Court frequently reviewed cases regarding the new Reconstruction Amendments. In the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873), brought by Louisiana livestock butchers, Justice Miller’s majority opinion interpreted these amendments for the first time. The 5-4 decision held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges and Immunities Clause was only intended to apply to formerly enslaved African Americans and thus did not affect the butchers, who claimed that the state was unreasonably interfering with their slaughterhouse operations. Justice Miller later wrote the unanimous holding in Ex parte Yarbrough (1884), which clarified voting rights for Black men under the Fifteenth Amendment. Writing for the Court, Miller explained that the amendment “clearly shows the right of suffrage was considered to be of supreme importance to the national government, and was not intended to be left within the exclusive control of the states.”

Commerce

At this point, the early Lincoln appointees of Justice Miller, Justice Noah Swayne, and Justice David Davis, who were relatively in agreement on constitutional questions during the Civil War and early Reconstruction, diverged. As the United States industrialized, the Justices debated how to apply the Constitution to legal questions generated by big business and workplace changes. Justice Miller, deeply affected by Keokuk’s decline, was more sympathetic to workers’ complaints as the Court heard challenges to the changes that came with new industry. Justice Miller’s opinions on bonds often put him in the minority and at odds with his fellow Lincoln-appointed Justices. He dissented in several bonds cases, including Butz v. Muscatine (1869), a case centered around a bond debt owed by an Iowa town. Justice Swayne wrote for the majority, concluding that the debt be paid in full despite Iowa statutes claiming an exemption. In his dissent, Justice Miller argued it was an “unqualified overthrow of the rule imposed by Congress…that the decisions of the state courts must govern this Court in the construction of state statutes.”

Justice Miller also issued opinions that opposed state interference in the federal regulation of interstate commerce. In Wabash, St. Louis, and Pacific Railroad Company v. Illinois (1886), the Court struck down an Illinois law that allowed the states to regulate long- and short-haul railroad rates. Justice Miller wrote for the majority “as matter of law that the transportation in question falls within the proper description of ‘commerce among the states,’ and as such can only be regulated by the Congress of the United States.” The decision paved the way for the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission the following year.

Legacy

Justice Miller walked home from the Court for the last time on October 10, 1890. During his journey, he suffered a stroke and died three days later. The stroke paralyzed him on one side, but Samuel continued to talk and joke with his doctors during treatment. Reportedly, when doctors told him not to strain his brain by talking, Samuel said that it was a “compliment for you must think that when I talk I use my brains.” He served for 28 years on the Court under four Chief Justices. Justice Miller remained a powerful force on the bench until the day he died. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase remembered Samuel as “beyond question the dominant personality…upon the bench, whose mental force and individuality are felt by the Court more than any other.”

Discussion Questions

- How did Samuel Miller’s background as a physician influence his law career?

- Samuel studied all of the Supreme Court decisions before his appointment to make up for his lack of judicial experience. What does this say about his character and how might it have helped him succeed?

- How did President Lincoln use the opportunity to appoint justices to the Supreme Court to his advantage? What did his nominations have in common?

- How did Justice Miller help interpret the Reconstruction Amendments?

- How would you summarize Justice Miller’s legacy and contribution to the Supreme Court?

Sources

Special thanks to legal history scholar and professor Michael Ross for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Official Portrait of Associate Justice Samuel Freeman Miller. Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Butz v. City of Muscatine, 75 U.S. 575 (1869)

Cushman, Clare, ed. The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Third Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, an imprint of SAGE Publications, 2013.

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651 (1884).

Gregory, Charles Noble. “Samuel Freeman Miller: Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.” The Yale Law Journal 17, no. 6 (1908): 422–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/784599.

Kahn, Michael A. “Abraham Lincoln’s Appointments to the Supreme Court: A Master Politician at his Craft.” Journal of Supreme Court History, 22-2: 65-78 (1997).

Ross, Michael A. “Hill-Country Doctor: The Early Life and Career of Supreme Court Justice Samuel F. Miller in Kentucky, 1816-1849.” The Filson Club History Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 4 (1997).

Ross, Michael A. Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Civil War Era. Louisiana State University Press (2003).

Ross, Michael A. “Melancholy Justice: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Gilded Age.” Journal of Supreme Court History, 33-2:134-148 (2008).

“Slaughter-House Cases.” Oyez. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/83us36.

Wabash, St. Louis, and Pacific Railway Company v. Illinois, 118 U.S. 557 (1886)