Edward Douglass White Jr.

Life Story: 1845-1921

The first Associate Justice to become the Chief Justice of the United States.

Background

Edward Douglass White Jr. was born on his family’s plantation in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana on November 3, 1845. His father, Edward D. White Sr., was a prominent Irish-Catholic attorney, politician, and slaveholding planter. He was also a city judge, five-term representative to Congress, and Governor of Louisiana from 1834 to 1838. Amidst his successful political career, he bought a sugar-beet plantation—which relied on labor from about 50 enslaved people—that stretched along a bayou about 70 miles west of New Orleans, a major trading port at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Governor White married Catherine Sidney Ringgold, a socialite from established families in Maryland and Virginia, in 1834. The couple had five children—three girls and two boys, including Edward Jr., known as “Ned” during his boyhood. The elder Edward died suddenly in 1847, widowing Catherine when Ned was just three years old. The plantation’s income kept the family financially stable. Catherine remarried in 1850 to André Brousseau, a French-Canadian immigrant and businessman, and moved the family to a townhouse in New Orleans’ bustling French Quarter.

The Whites were a devout Catholic family, and all of Ned’s school was rooted in those values. He attended a convent in New Orleans starting at age 6, and, two years later, travelled north to attend a Jesuit boarding school at Mount St. Mary’s Prep in the mountains of western Maryland. In the fall of 1857, 12-year-old Ned continued his Catholic education at Georgetown College (now Georgetown University) in Washington, D.C. He studied the classics, music (flute and violin), and was part of the cadet corps, a student military leadership organization. The Civil War began in 1861 and cut Ned’s education short. Like most Southern students attending a Northern school, he moved back home at the beginning of the war and joined the Confederate Army. Ned was just 15 years old, and records indicated that he likely served as an aide rather than on the fighting lines. In May of 1863, the Union Army seized Port Hudson, Louisiana, trapping Ned and thousands of other Confederate troops for weeks. By the end of the siege in July, Ned was extremely ill and emaciated. Little is known about his whereabouts for the next couple of years. Records show, however, that Union forces captured him on March 12, 1865. They held him at a prison in New Orleans, not far from his home. Shortly thereafter, on April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered, and Union General Ulysses S. Grant ordered all Confederate prisoners of war to be released. Union forces sent Ned up the Mississippi River river for a prisoner exchange He was officially released at Red River Landing, where the two armies had just concluded one of the war’s final battles, and then sailed back home to New Orleans. Ned later reflected that “like everybody else in my environment, as a little boy I went to the army on the side that didn’t win.” Later in life, he became dear friends with Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had fought against him in the Union Army. Every year on the anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest battle in the Civil War, he placed a bouquet of violets on the desk of Justice Holmes’ desk as a gesture of reconciliation.

Early Career

With the Civil War now over, Edward (“Ned” was a childhood nickname) began his law career in the fall of 1865. He attended the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University), just down the street from where he had been imprisoned six months earlier. In addition to law school, he apprenticed under a prominent local attorney. Edward passed the Louisiana bar exam in 1868 and started practicing law in New Orleans. Following in his family’s tradition, he also became an active politician. His fellow Louisianans elected him to the Louisiana State Senate in 1874 to represent the Democratic party. During his term, he supported Francis T. Nicholls’ campaign for governor. Nicholls won the election and soon after appointed Ned to the Louisiana State Supreme Court, where he served from 1878 to 1880.

Edward returned to private practice for the next 10 years, working with some of the most prominent firms in New Orleans. He remained involved in politics, and also picked up some civic projects, including helping to establish Tulane University in 1884. There was plenty of time for pleasure, too. Being both financially secure and fluent in French allowed him to enjoy fully the city’s vibrant culture and cuisine. While living in New Orleans, he met Virginia Montgomery Kent, who would later—after a 20-year courtship—become his wife in 1894. Though the couple never had any children of their own, Edward reportedly adored them and often carried candy in his pockets to share with children he encountered.

Supreme Court

Nicholls became governor again in 1888 and the state legislature appointed Edward to the United States Senate (Senators would not be directly elected by the people until the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified in 1913). Senator White served for three years (1891 to 1894), placing him on the national political stage. His work as a legislator caught the attention of President Grover Cleveland. When a vacancy opened on the Supreme Court bench, although the Louisiana Senator was not the President’s first choice for the seat, President Cleveland nominated Edward on February 19, 1894. The Senate confirmed his appointment the same day, after rejecting President Cleveland’s two previous nominees. Sixteen years later, Republican President William Howard Taft nominated Edward to be Chief Justice of the United States following the death of Melville Fuller. He was the first Associate Justice to be elevated to be Chief Justice, and was chosen in part because of his pleasant and agreeable nature. Chief Justice White served until his death in 1921.

Rights

Justice White’s 27-year tenure overlapped with a pivotal time for race and civil rights. Decades after the Civil War ended, the country continued to grapple with the meaning of the Reconstruction Amendments. Justice White considered these issues on a case-by-case basis. In regard to the Fourteenth Amendment, he sided with the majority in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which reasoned that “separate but equal” facilities complied with the Equal Protection Clause. Later in his career, Chief Justice White authored the Court’s decision to strike down grandfather clauses in Guinn v. United States (1915). The unanimous decision found that an Oklahoma voting law “inherently brings [discrimination] into existence, since it is based purely upon a period of time before the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment.” Around the same time, the U.S. annexed several overseas territories including Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines during the era of American imperialism. Justice White led the Court in identifying how and when to apply the country’s Constitution and laws to the new colonies. In a series of decisions known as the Insular Cases, the Court held that the Constitution applied fully only to territories that were incorporated (made legally part of the United States) by Congress.

During World War I and the First Red Scare, Chief Justice White’s decisions affirmed the federal government’s concern for national security. For example, he authored the majority opinion that confirmed the constitutionality of the Selective Service Act. In the Selective Draft Law Cases (1918), he wrote for the Court that “compelled military service is neither repugnant to a free government nor in conflict with the constitutional guarantees of individual liberty.” In 1919, he sided with the majority when challenges arose to the Espionage Act of 1917. The Court upheld the Acts, which criminalized speech or activity that interfered with the war effort, in both Debs v. United States, Schenck v. United States and Abrams v. United States.

Commerce

At the turn of the 20th century, the Justices frequently reviewed cases involving the power of the states and the federal government to regulate commerce. In 1890, for example, Congress attempted to limit monopolies’ power and promote fair competition by passing the Sherman Antitrust Act. Though the act outlawed “every contract, combination…or conspiracy in restraint of trade or commerce,” Justice White argued that it should not apply to all large corporations. In Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States (1911), he wrote that the Sherman Act barred only monopolies that unreasonably restrained trade in a way that created higher prices, reduced output, or reduced quality—including John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. The Court used this logic, known as the rule of reason, to evaluate large corporations for years to come.

Reform

In considering legal challenges to Progressive reforms, Justice White generally applied the principle of federalism. When the Court struck down a New York law setting maximum working hours for bakers in Lochner v. New York (1905), Justice White dissented. He joined Justice John Marshall Harlan’s opinion, which defended the state legislature’s authority to create the law. On the federal level, Justice White authored opinions that affirmed the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission. He also sided with the majority to uphold some federal consumer protections, including the Pure Food and Drug Act. He evaluated cases regarding labor, however, on an individual basis. He agreed with the majority in upholding maximum work hours for women in Muller v. Oregon (1908), but voted against upholding legislation that limited “yellow-dog contracts,” which prohibited workers from joining unions as a condition of employment .

Legacy

Even as the Chief Justice’s eyesight began to fail, he insisted on working as long as he could. He fell ill on May 13, 1921, and died six days later at age 75. During his 27-year tenure on the Court, Edward Douglass White played a critical role in interpreting the law in the rapidly transforming post-Civil War and industrial United States. Though Edward spent much of the first half of his career in a partisan space—first as a Confederate soldier, and then as a Democratic politician—the opinions he authored for the Supreme Court defied political categorization and transcended post-Civil War regional conflict.

Discussion Questions

- How do you think Justice White’s upbringing influenced his career and political views?

- How did Justice White’s decisions reflect the large-scale industrialization happening in the United States?

- During World War I, Chief Justice White and the Court’s majority affirmed laws that allowed the federal government to restrict freedom of speech if the speech might pose a threat to national security. Do you agree with this idea? Why or why not?

- How did Justice White’s decisions reflect the principle of federalism?

Sources

Special thanks to legal scholar and professor Andrew Kent for his review, feedback, and additional information.

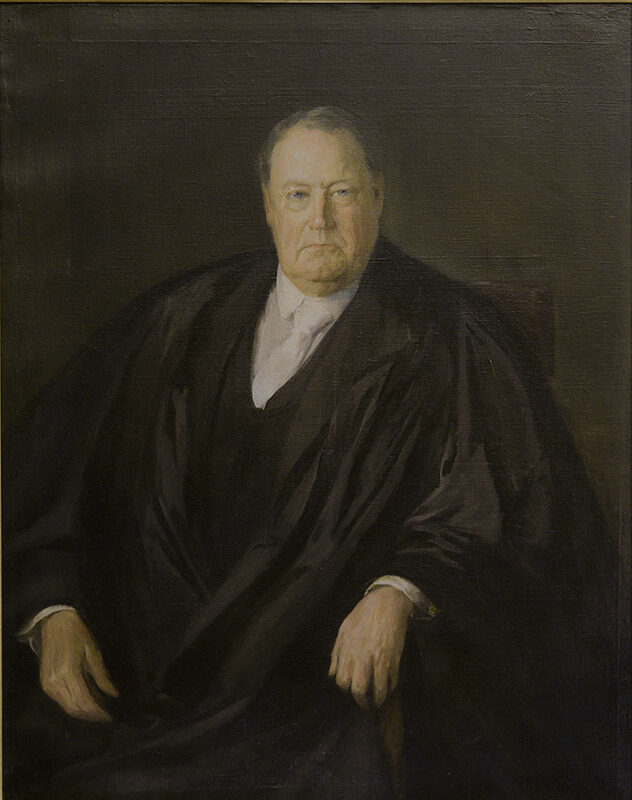

Featured image: Official portrait of Chief Justice Edward D. White. Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

“Chief Justice White is dead at age of 75 after an operation,” New York Times, 19 May 1921.

“Edward D. White (1910-1921). Supreme Court Historical Society. https://supremecourthistory.org/chief-justices/edward-white-1910-1921/.

Kent, Andrew. “The Rebel Soldier Who Became Chief Justice of the United States: The Civil War and its Legacy for Edward Douglass White of Louisiana.” The American Journal of Legal History 50, no 2 (2016): 209-264.

Shoemaker, Rebecca S. The White Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacies. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, Inc., 2004.