Incorporating Rights

During the 1950s and 1960s, Supreme Court decisions addressed issues involving individual rights in the civil rights movement, the apportionment of voting, police procedures, and the scope of state power in areas such as birth control and school prayer.

Background

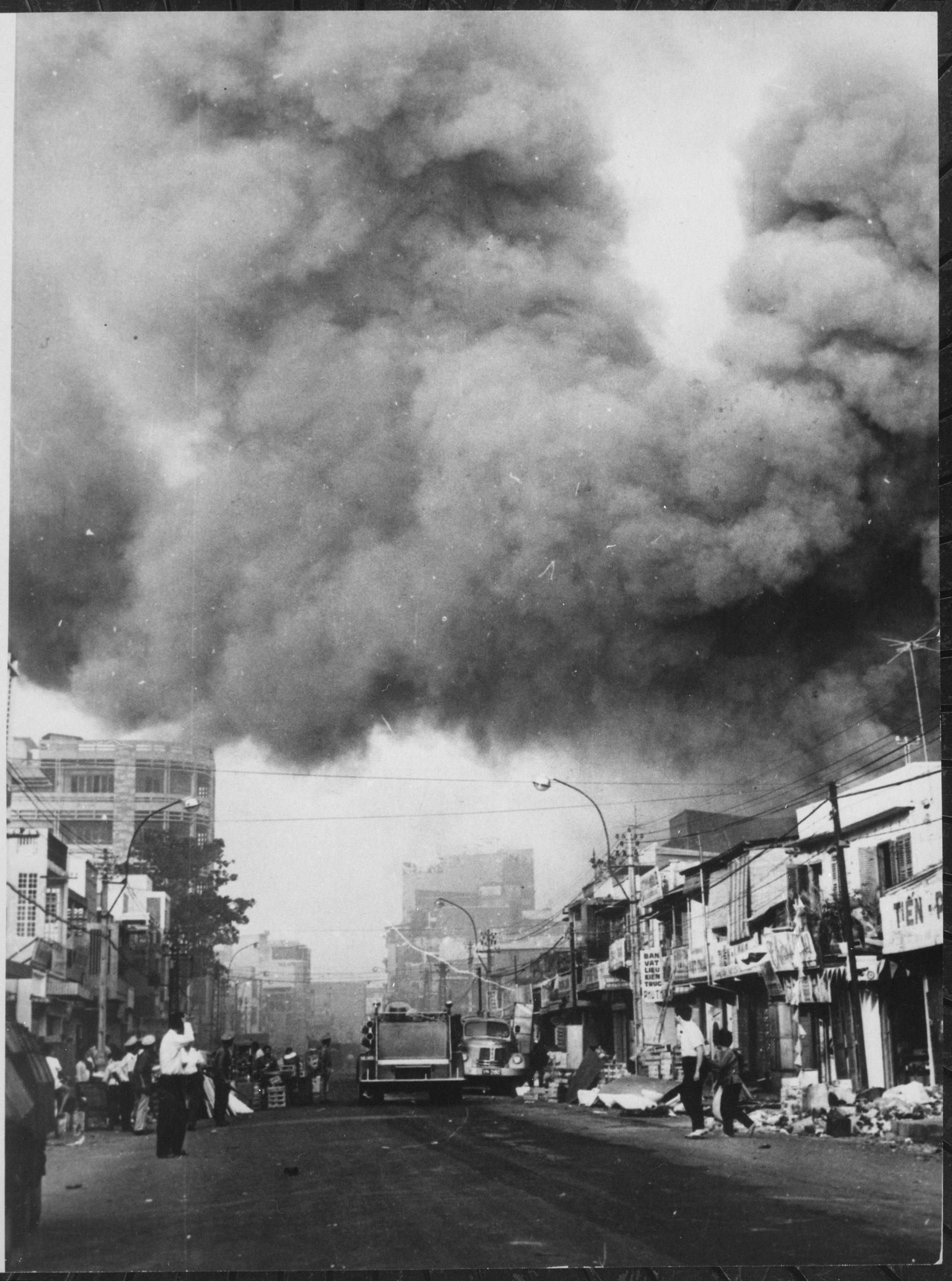

In the 1950s, the United States was still experiencing the hopes and challenges of the post-World War II era. Mass hysteria about the threat of communism swept the country as the U.S. engaged in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. Civil liberties were threatened by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee, which accused hundreds of people of being communists, ending the careers of many. The threats of nuclear war and the spread of communism lingered throughout the decade. At home, schoolchildren practiced “duck and cover” drills. Abroad, U.S. soldiers fought communist powers in Korea and developed an increasing presence in Vietnam.

The end of World War II also created unprecedented economic growth. Between 1945 and 1960, the average family income increased from $2,200 to $8,000 per year. Additionally, the GI Bill financed college tuition for returning veterans and made buying a home more affordable. By 1960, the rate of homeownership in the U.S. reached 62 percent, compared to 43.6 percent 20 years earlier. However, these economic benefits were largely enjoyed by the white middle class. Across the nation, Black Americans were systematically excluded from the benefits of the GI Bill. They were frequently denied mortgages, and the new suburban neighborhoods where many white families moved often had racially restrictive housing covenants. In addition, Jim Crow laws and other racially biased legislation segregated all aspects of public life, from schools to movie theaters to water fountains. Other groups also continued to face discrimination, including Mexican Americans, Native Americans, women, and the LGBTQ+ community.

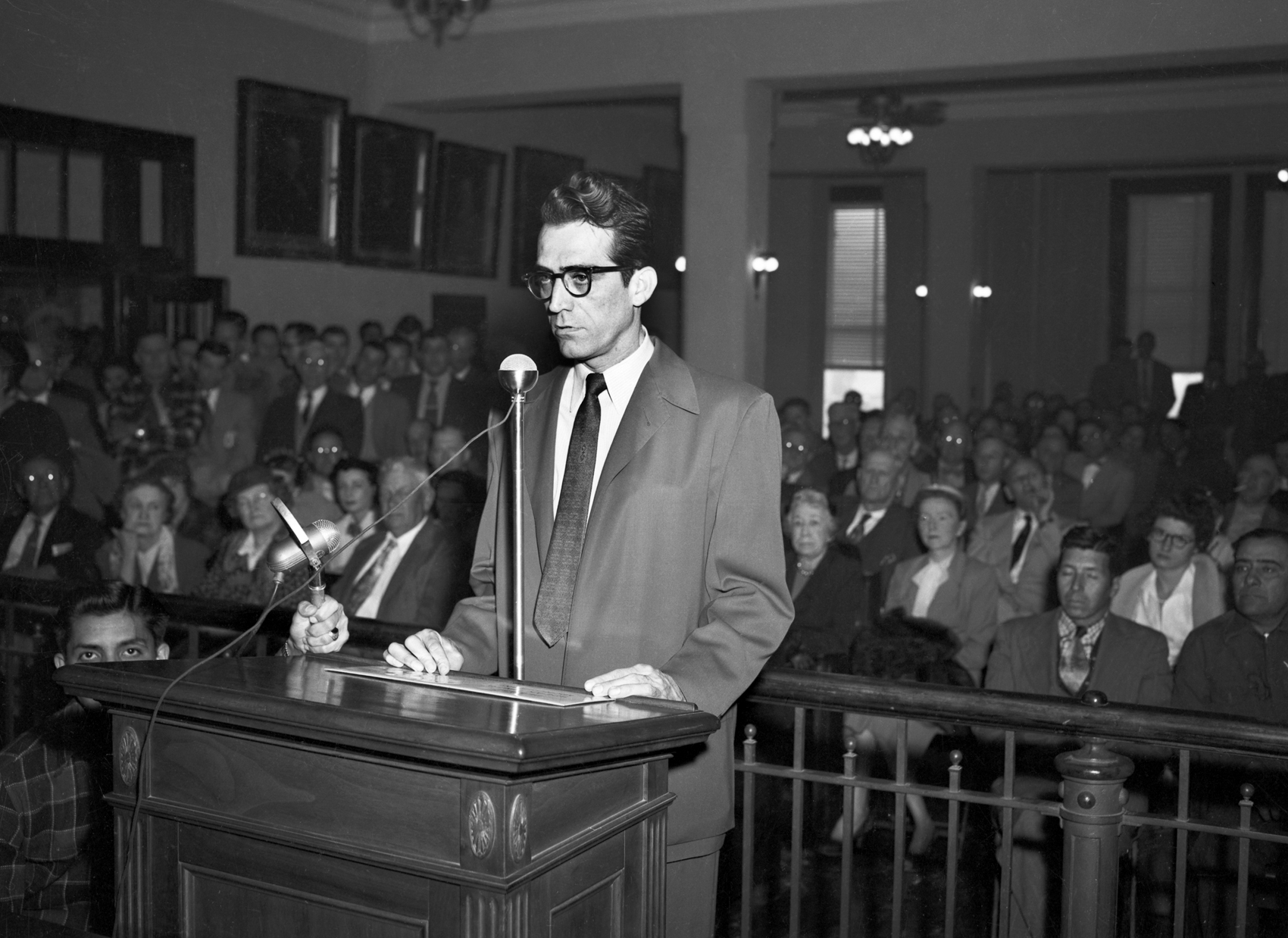

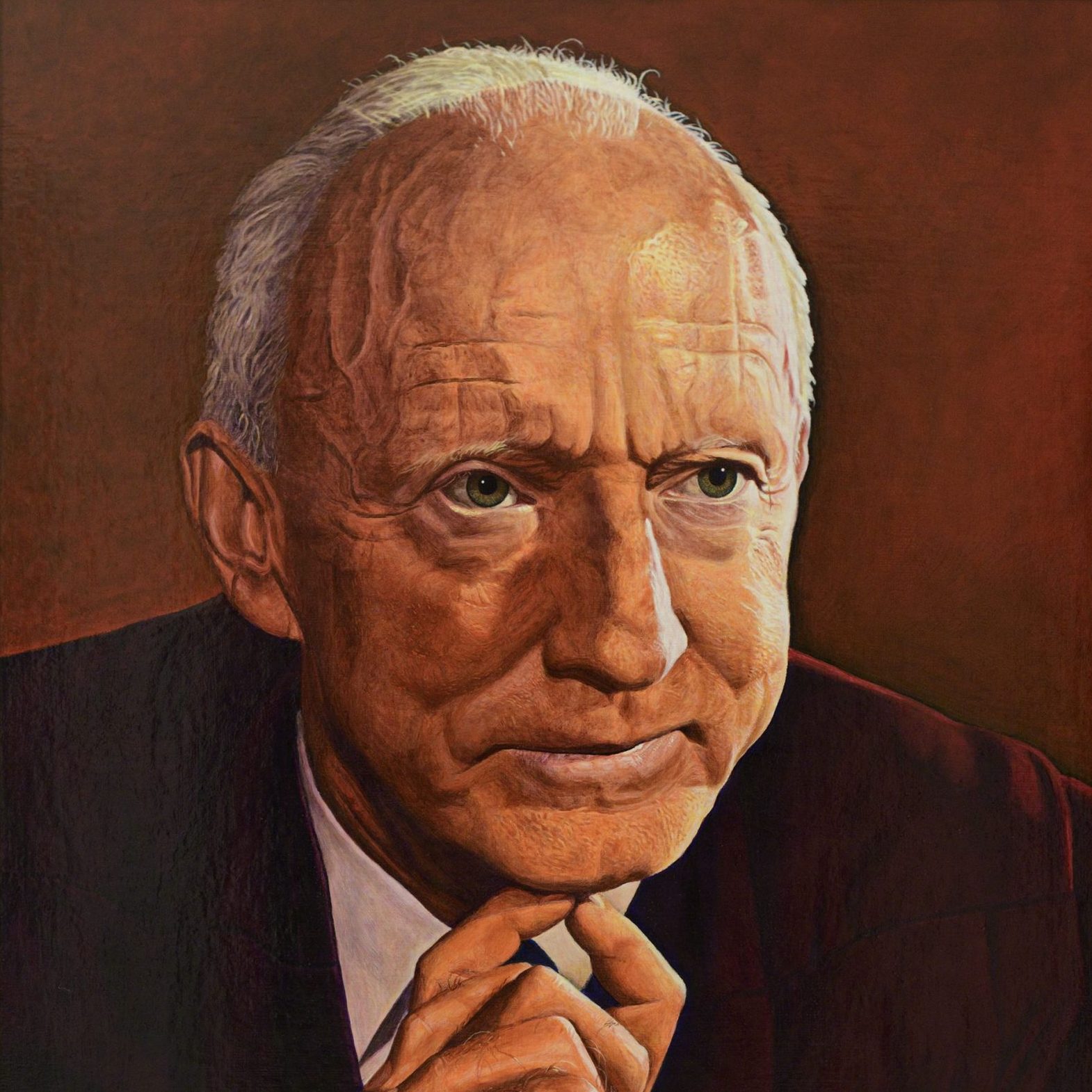

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights advocates fought for marginalized groups and challenged the status quo. They raised questions about constitutional rights, using the Fourteenth Amendment to argue that all persons are entitled to equal protection under the law. They also brought cases to the Supreme Court about the protections of the First Amendment and the rights of the accused. From 1953 to 1969, under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court addressed pressing constitutional questions about individual rights and freedoms.

Discussion Questions

- Describe the impact of the Warren Court’s decisions on the Civil Rights Movement.

- How did the African-American Civil Rights Movement impact other rights movements?

- A democracy is a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives. Why was the Court’s decision in Baker v. Carr important to democracy?

- To what extent did the Supreme Court contribute to the expansion of individual rights from 1953-1969?

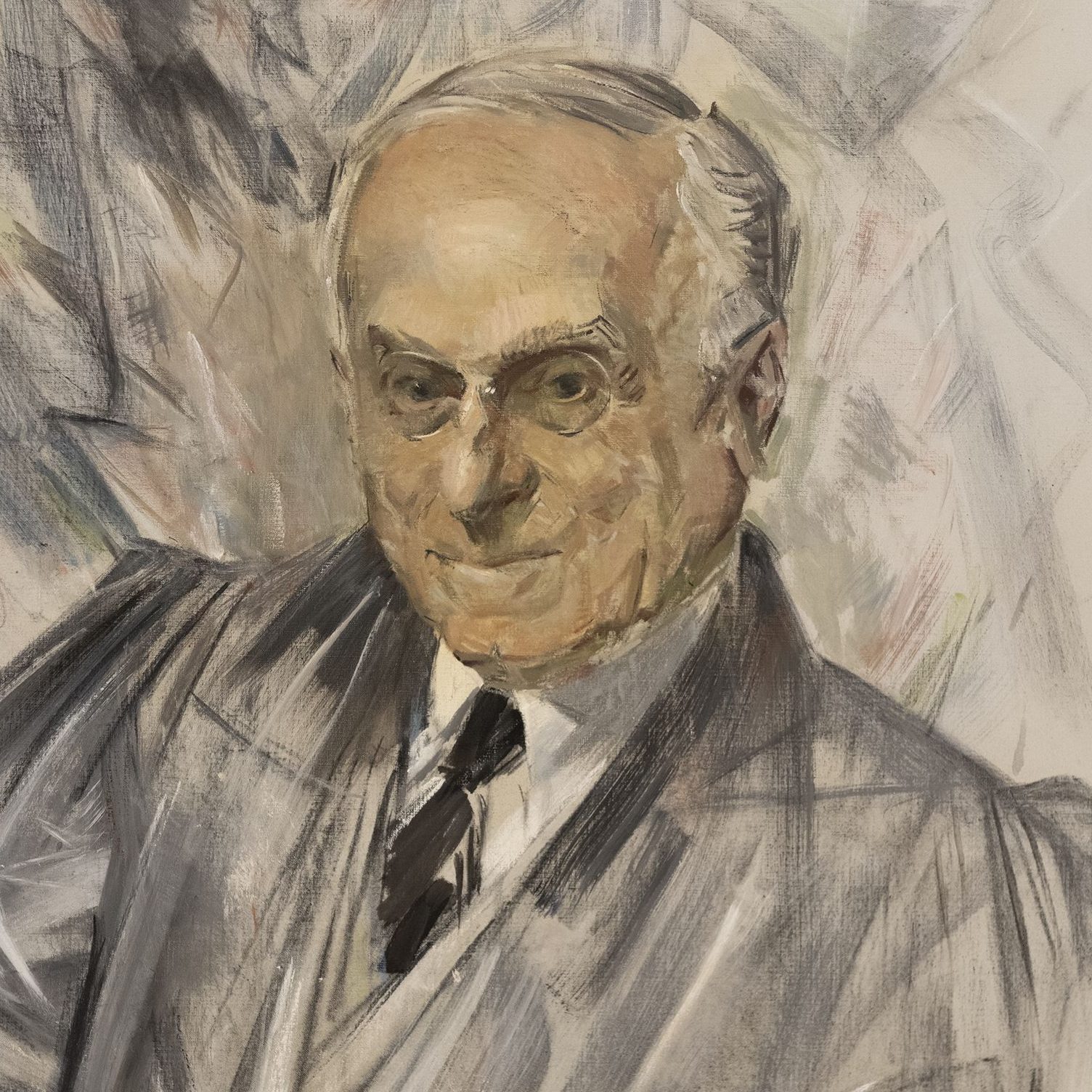

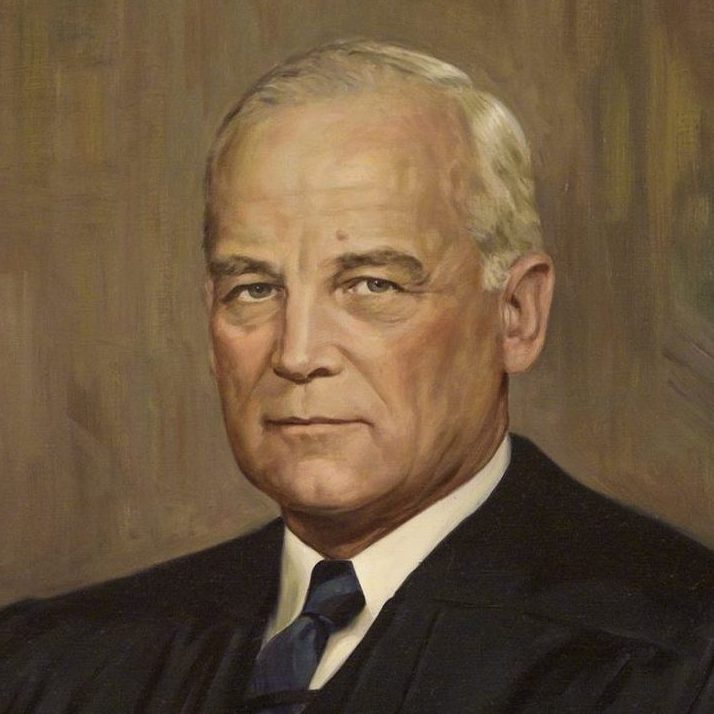

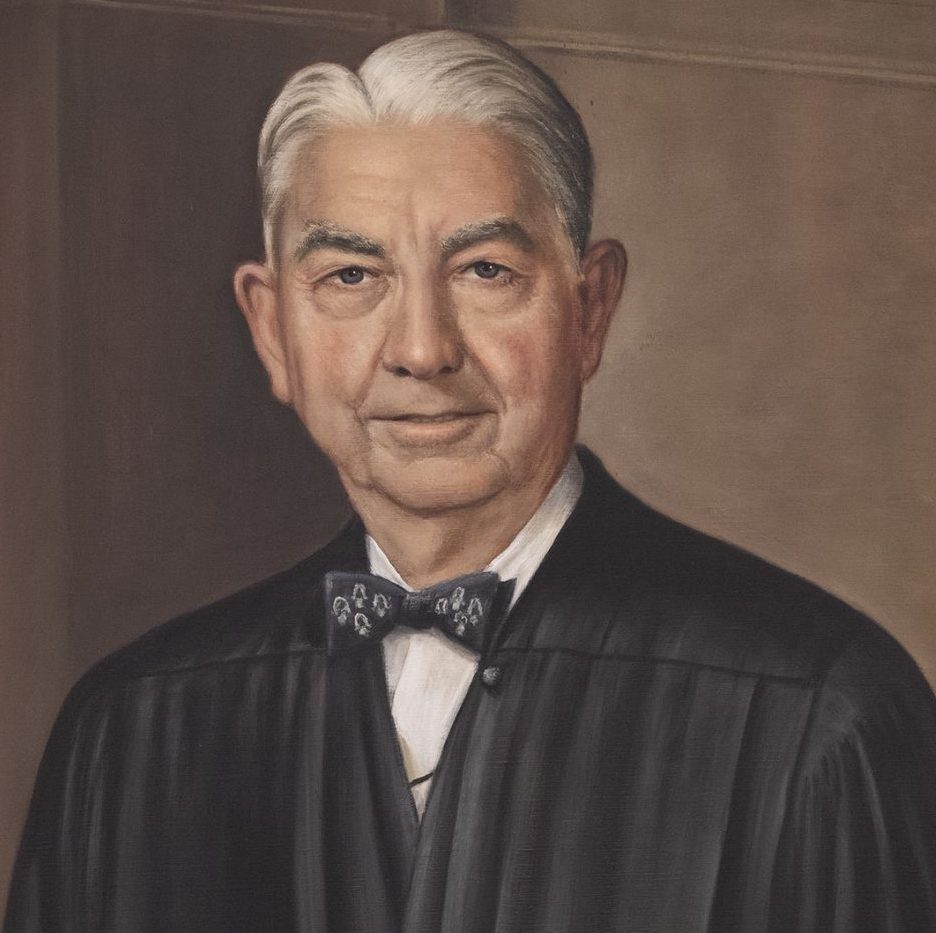

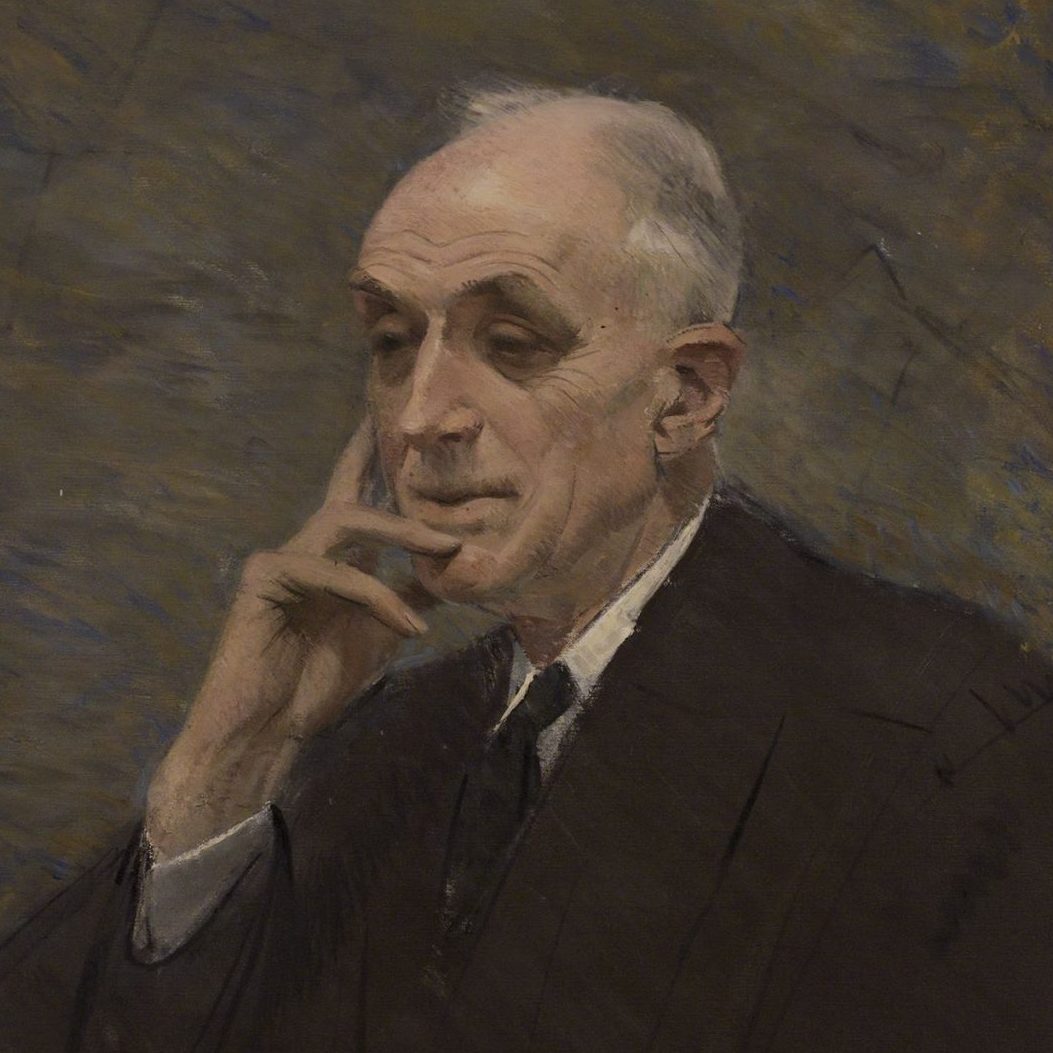

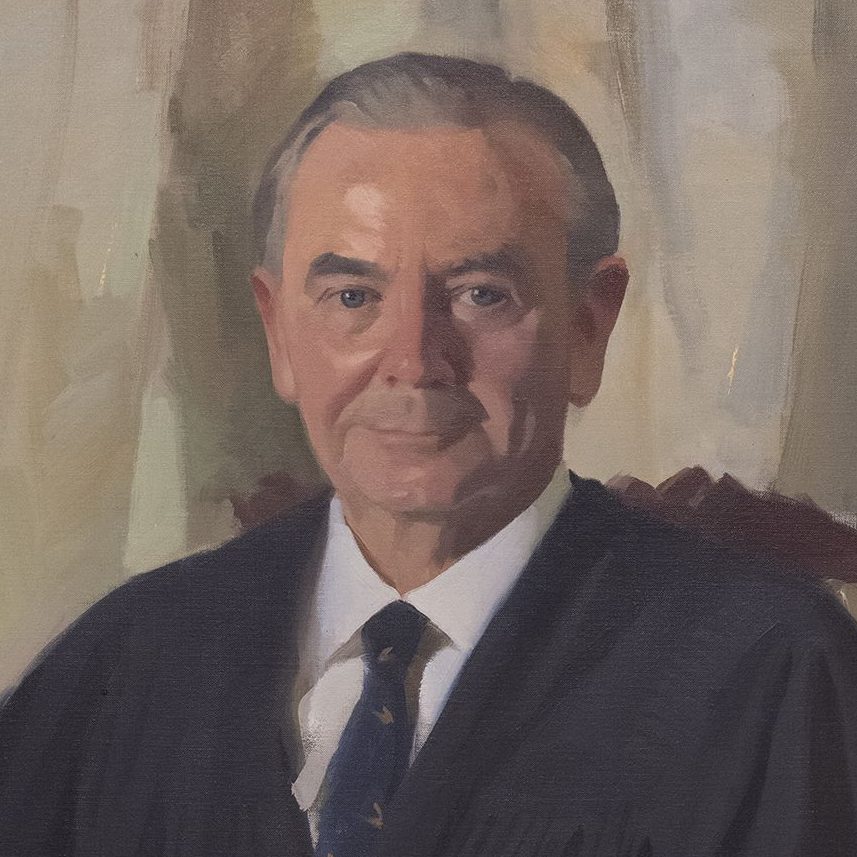

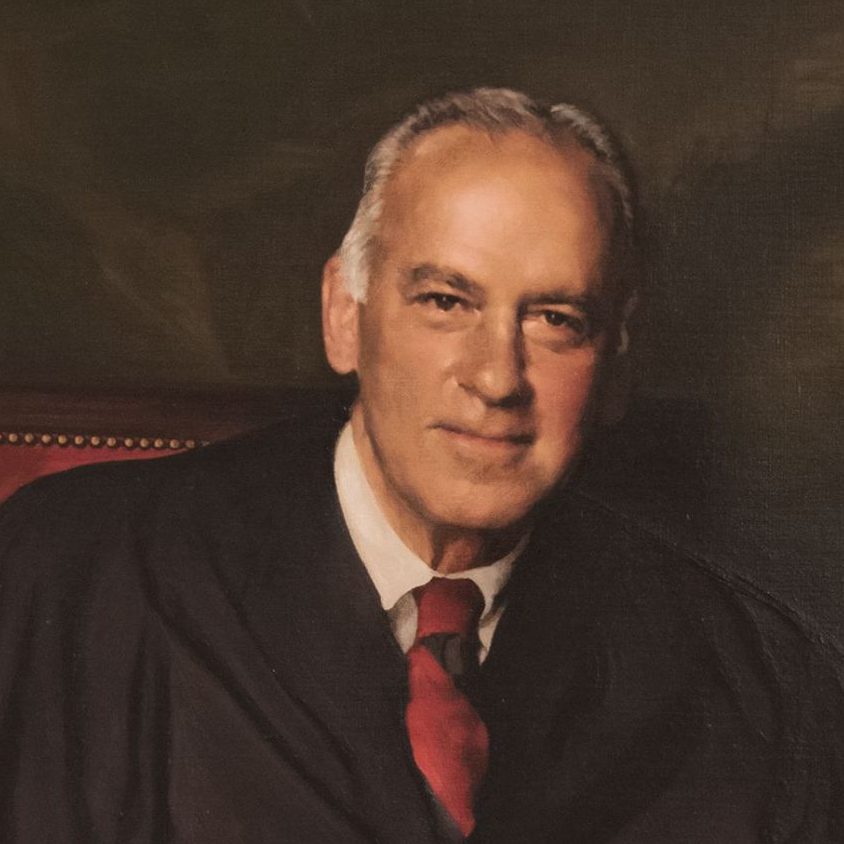

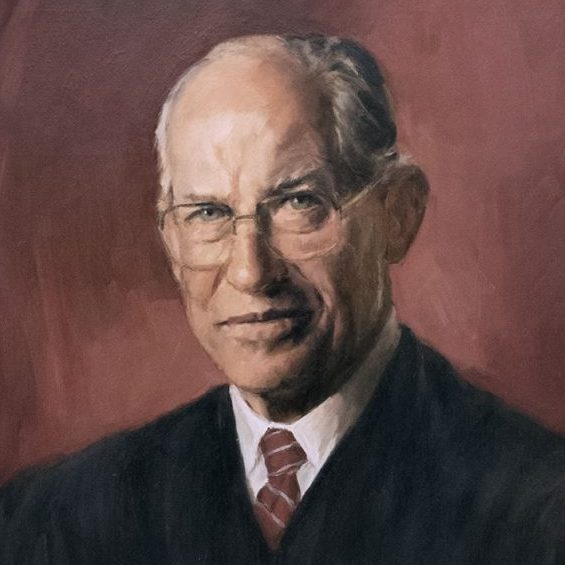

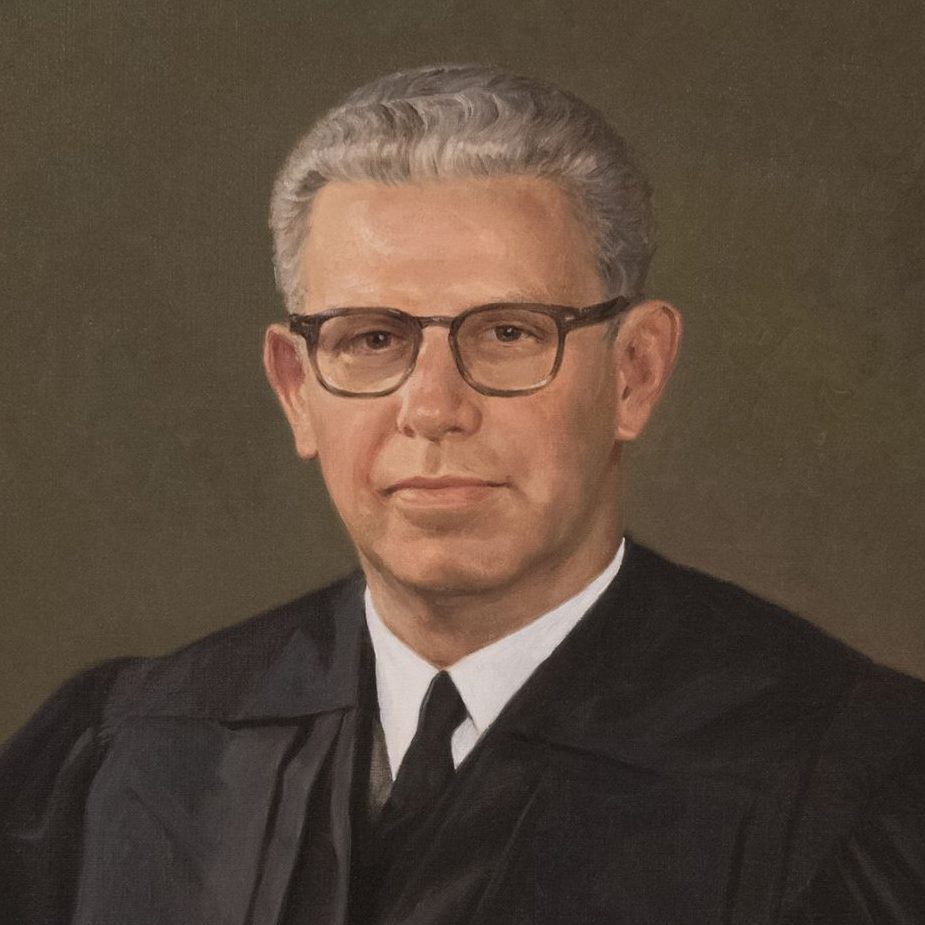

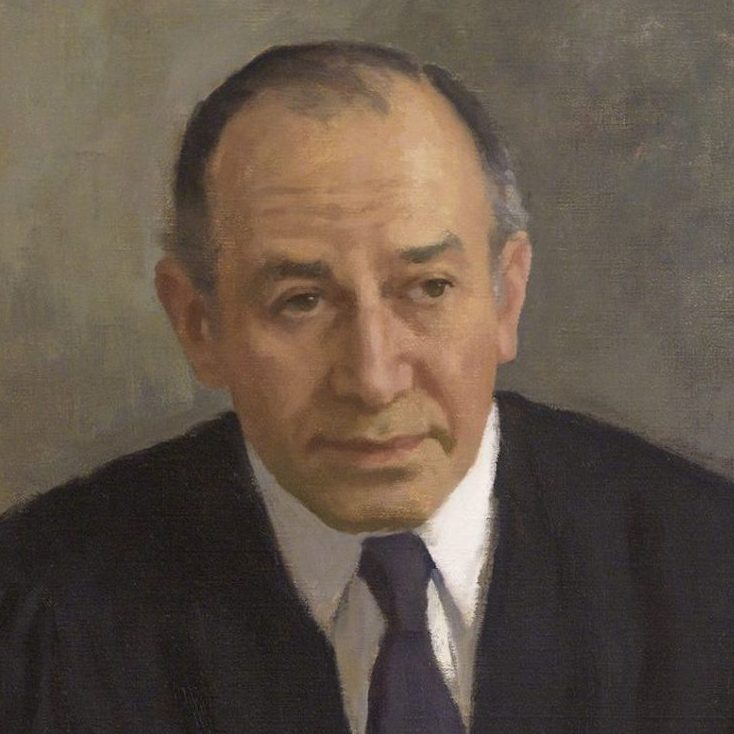

Supreme Court Justices

Chief Justice-

19531969

Earl Warren

-

19371971

Hugo L. Black

-

19381957

Stanley Reed

-

19381962

Felix Frankfurter

-

19391975

William O. Douglas

-

19411954

Robert H. Jackson

-

19451958

Harold Burton

-

19491967

Tom C. Clark

-

19491956

Sherman Minton

-

19551971

John Marshall Harlan II

-

19561990

William J. Brennan Jr.

-

19571962

Charles E. Whittaker

-

19581981

Potter Stewart

-

19621993

Byron R. White

-

19621965

Arthur J. Goldberg

-

19651969

Abe Fortas

-

19671991

Thurgood Marshall

Significant Cases

-

1954

Hernandez v. Texas

The Supreme Court case that recognized Mexican Americans as an independent racial group entitled to Fourteenth Amendment protections.

-

1954

Brown v. Board of Education

The landmark Supreme Court decision that declared public school segregation unconstitutional and led to wider civil rights victories in the 1960s.

-

1956

Browder v. Gayle

The Supreme Court’s affirmation of a district court decision to outlaw segregated bussing in Montgomery, Alabama that overturned Plessy v. Ferguson.

-

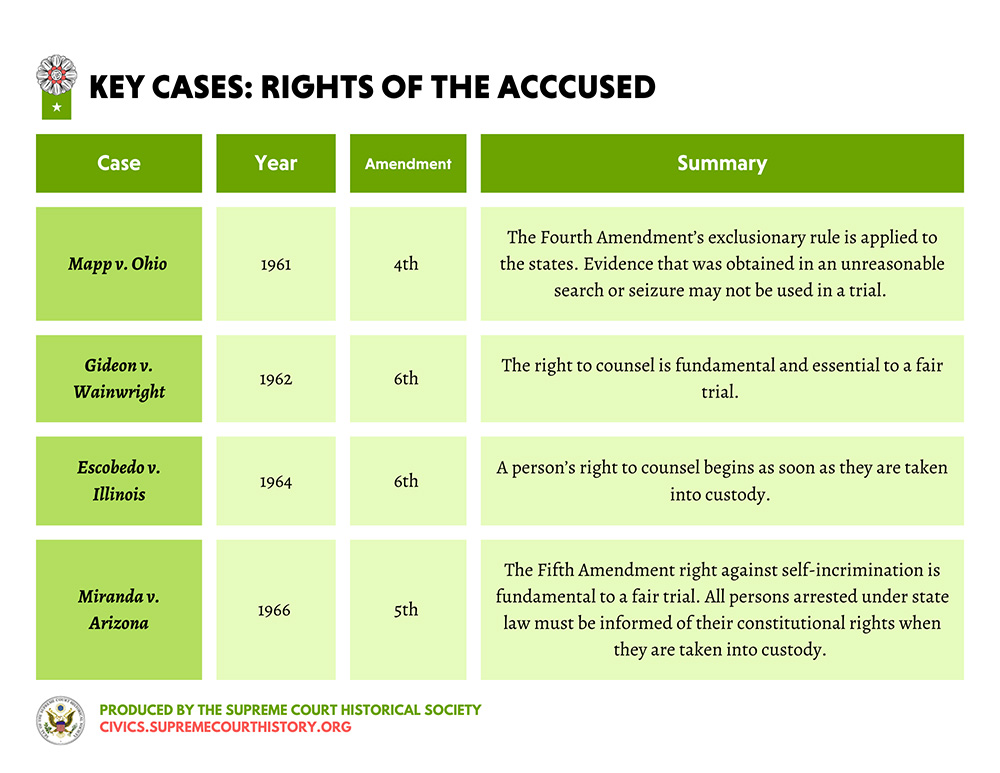

1961

Mapp v. Ohio

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that held illegally obtained evidence is inadmissible in state courts

-

1961

Engel v. Vitale

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that determined school-sponsored prayer is unconstitutional

-

1962

Baker v. Carr

The landmark case that declared unequal representation in legislative districts to be unconstitutional and that the courts have jurisdiction over questions of legislative apportionment

-

1963

Gideon v. Wainwright

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that incorporated the Sixth Amendment right to counsel

-

1964

Escobedo v. Illinois

The Supreme Court decision that affirmed a person has a Sixth Amendment right to consult a lawyer as soon as the police focus on them as a suspect

-

1964

New York Times Company v. Sullivan

The Supreme Court decision that arose during the Civil Rights Movement and protected freedom of the press

-

1965

Griswold v. Connecticut

The first Supreme Court case linking reproduction to the right to privacy.

-

1966

Miranda v. Arizona

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision establishing that police must inform suspects of their rights

-

1967

Loving v. Virginia

The Supreme Court decision that upheld equal protection and due process in regard to interracial marriage.

-

1969

Tinker v. Des Moines

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision that stated students have free speech rights in public schools

Resources

-

Selective Incorporation

Selective incorporation is the case-by-case application of the Bill of Rights to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. It can applied by the Supreme Court when citizens request review of state regulations that they believe infringe on civil liberties protected under the Bill of Rights.

Read more

-

Brown as the Beginning

The landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954) declared public school desegregation unconstitutional, but its impact on segregation was neither immediate in 1954 nor has it ended segregation.

Read more

-

The Roles of Wives: 1953-1969

The wives of justices supported their husbands, pursued their own interests, and managed their households and families.

Read more

-

Women in Law: 1953-1969

A small but growing number of women pursued law careers and advocated before the Supreme Court during the 1950s and 1960s.

Read more

-

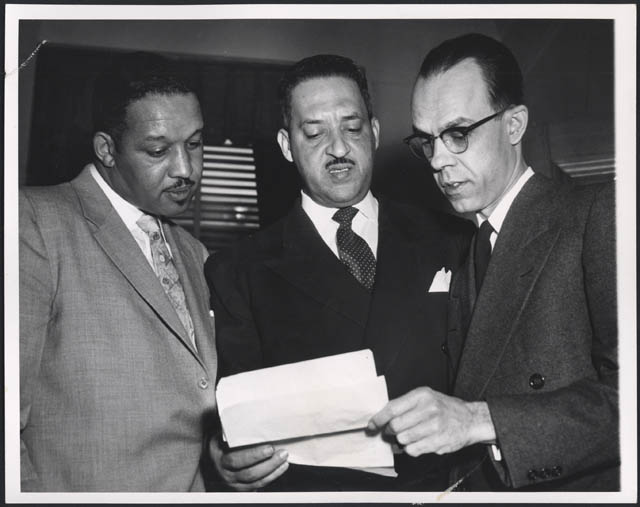

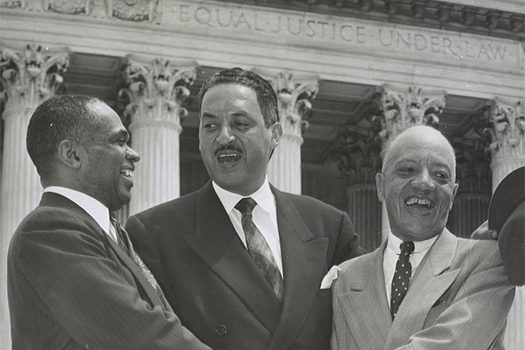

Thurgood Marshall as an Advocate

Before Thurgood Marshall became a Supreme Court Justice, he advocated for civil rights as a lawyer with the NAACP.

Read more

Significant Events In U.S. History

Did You Know

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenter in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which the Supreme Court overturned with its Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and Browder v. Gayle (1956) decisions.

Read more

Did You Know

Miriam Naveira Merly was the first woman of Puerto Rican descent to argue before the Supreme Court of the United States and the first woman to serve as the Chief Justice of the Puerto Rican Supreme Court.

Read moreSources

Special thanks to scholars and law professors David Levy and Morton Horwitz for their review, feedback, and additional information.

Bethune, Brett. “Influence Without Impeachment: How the Impeach Earl Warren Movement Began, Faltered, But Avoided Irrelevance.” Journal of Supreme Court History 47, no. 2 (2022): 142-161.

Branch, Taylor. “The Civil Rights Movement.” Period 8: 1945-1980. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ap-us-history/period-8#par-5973.

Brinkley, Allen. “The Fifties.” Period 8: 1945-1980. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ap-us-history/period-8

Corbett, P. Scott et. al. Chapter 29 Contesting Futures: America in the 1960s and Chapter 30 Political Storms at Home and Abroad, 1968-1980. U.S. History. OpenStax (2014). https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history.

Urofsky, Melvin I. The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, 2001.

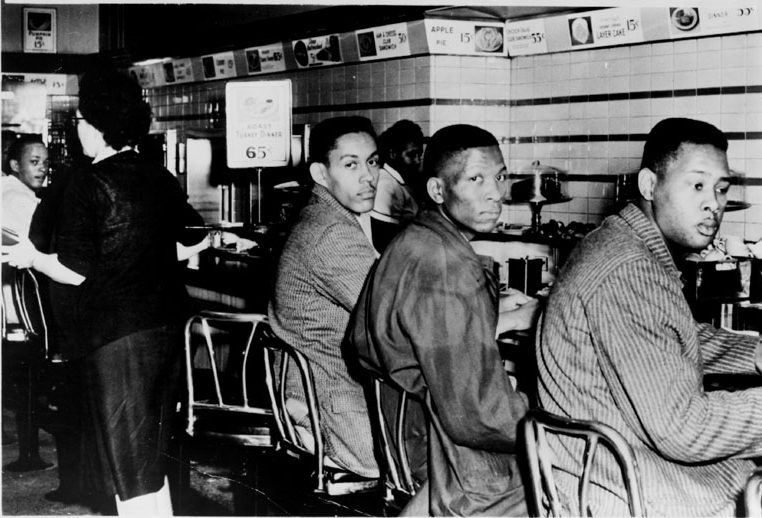

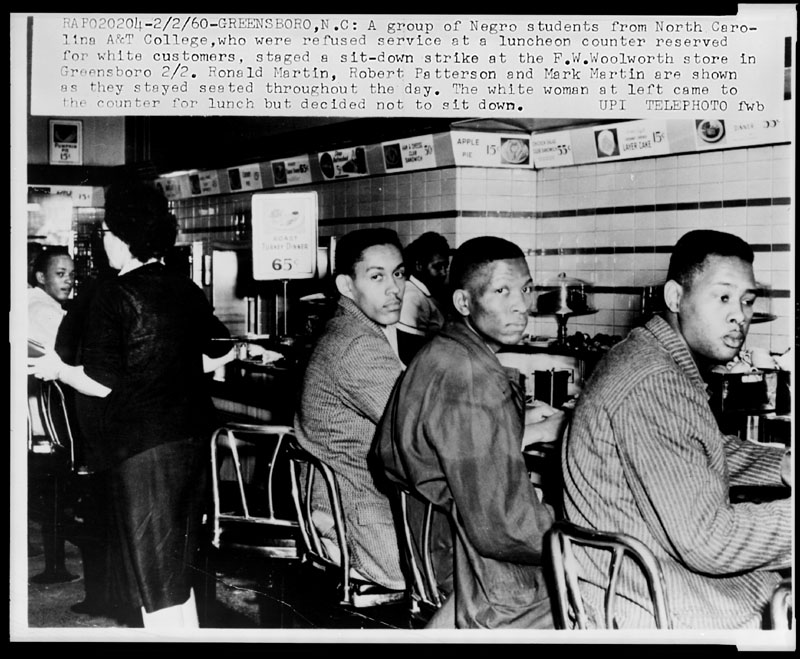

Featured image: Ronald Martin, Robert Patterson, and Mark Martin stage sit-down strike after being refused service at a F.W. Woolworth luncheon counter, Greensboro, N.C. North Carolina Greensboro, 1960. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/95512251/.

All portraits and images of the Warren Court Justices are from the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Incorporating Rights: 1953–1969