Brown as the Beginning

Significant Case

The landmark Supreme Court decision that declared public school segregation unconstitutional and led to wider civil rights victories in the 1960s.

Background

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) is the case that ended school segregation and overturned Plessy v. Ferguson’s (1896) “separate but equal” precedent. In this case, the Court found that school segregation was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The decision was the turning point in the country’s struggle for equal protection under the law for all of its citizens with particular application to education. It also gave encouragement to the Civil Rights Movement. Brown’s impact on segregation, however, was neither immediate in 1954 nor has it ended segregation. In some ways, the struggle continues today.

From the very beginning, the country’s support of the case was complicated. Brown clearly stated that “in the field of public education, ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” but gave no details about how to implement it. Even school districts that implemented desegregation plans still had de facto segregation, including those in the North that legally desegregated schools long before Brown. The decade following the Court’s unanimous opinion in Brown was filled with resistance. States in the South avoided implementation, and varying degrees of presidential support weakened its impact. Thus, Brown v. Board of Education did not immediately mark the end of school desegregation, but rather marked the beginning of progress both at the state and national levels.

President Eisenhower and Brown

In the realm of civil rights, President Eisenhower believed in leading by example, stating “I do not believe we can cure all the evils in men’s hearts by law.” He took action on the federal level, hoping the states would follow. For example, during his first eight months in office, he desegregated restaurants in Washington D.C., challenged segregation practices in schools on military bases, and created the Committee on Government Contracts to oversee fair hiring practices in the allocation of federal contracts. He was, however, conflicted about how swiftly Brown could be implemented.

Eisenhower and his attorney general researched the Fourteenth Amendment and agreed with the Supreme Court’s stance: segregated schools created inequality and were therefore unconstitutional. Still, President Eisenhower maintained that federal power should not be used to push segregated states towards dramatic social change. He stated, “these people in the South were not breaking the law for the past 60 years…Now we cannot erase the emotions of three generations just overnight.” With enough time to adjust, he believed, segregated states would comply with the Court’s ruling.

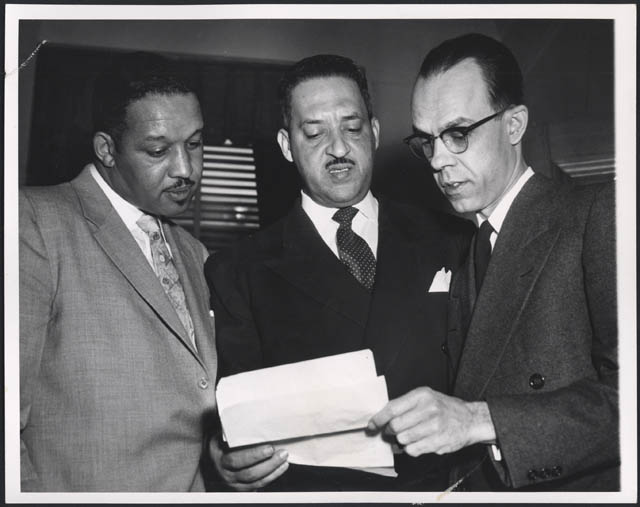

His hopes were unfulfilled. In February 1956, over a year and a half after Brown, the University of Alabama defied a court order to admit a Black student. President Eisenhower refrained from federal intervention. The school stayed segregated for seven more years (into President Kennedy’s term). Then, in September 1957, the Little Rock Nine students endured a week of unsuccessful attempts to go to class at Central High School. First, the Arkansas Governor ordered the National Guard to block their entrance. Then, mobs made it unsafe to attend at all. Finally, the head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stated that the nine children would not return until they had the protection of the president. It was at this point that President Eisenhower recognized that some segregated schools and universities would turn to violence before integrating. Letting the states implement the decision at their own pace would not work. In an unprecedented move, Eisenhower authorized the deployment of federal troops to Little Rock on September 23, 1957. The National Guard accompanied the students into Central High on Wednesday, a week and a half after the first day of school, and more than three years after Brown.

Brown II and Southern Resistance

The Court followed up with Brown in April 1955 by instructing states to implement school desegregation with “all deliberate speed.” Chief Justice Warren intentionally left the phrase undefined, and this vague statement had consequences. Brown II required school boards to submit plans to the federal courts for approval, but gave no deadline. Cities bordering Southern states, like Baltimore, Louisville, St. Louis, and Washington D.C., started their desegregation plans by the fall of 1954, but some Southern states refused to comply. They used pupil placement laws, provided state-sponsored tuition for private schools, created Citizens’ Councils, and denied state funds to desegregated schools as methods of massive resistance. In Mississippi and Louisiana, attending a desegregated school became a criminal act. Some school districts closed desegregated schools altogether.

The 1956-1957 school year reflected these policies. Out of 10,000 districts across 17 segregated states, only 723 complied with Brown II. Additionally, in 1957, the Arkansas governor ordered the National Guard to keep nine African-American students out of Central High School. In response to the actions of the governor and violent mobs outside the school, President Eisenhower sent federal troops to protect the students throughout the year. The Little Rock conflict did not end there. In Cooper v. Aaron (1958), the Court denied a petition from Central High’s school district that requested permission to suspend their desegregation plan until the 1960-1961 school year. Rather than integrate, the governor closed all high schools in Little Rock for a year. Similarly, public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia shut down, depriving Black students of any formal education from 1959 until 1963. Without the cooperation of local and state legislatures, the Court had no way to enforce Brown and Cooper.

Resistance was not confined to local and state actions. In March of 1956, 101 members of Congress (both the Senate and the House of Representatives) signed the Southern Manifesto, which declared their opposition to Brown and their desire to have it reversed. In directing the implementation of desegregation with “all deliberate speed,” the Court enabled the delay of school integration. State responses to Brown I and Brown II showed that these cases marked only the beginning of desegregation, not the end.

Civil Rights After Brown

Brown was one of the first federal actions to target racial segregation since the end of Reconstruction, but it would take executive, legislative, and civic action to create the change that the decision sought to achieve. President Lyndon B. Johnson made the civil rights agenda a domestic priority, and his administration passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act included a provision that tied federal funding to desegregation, which proved extremely effective. In the 1963- 1964 school year, a decade after Brown, 1.2 percent of African-American children attended integrated schools in Southern states. Ten years later, that number rose to over 90 percent. Federal legislation helped to finish what Brown started.

The short-term ineffectiveness of the Brown decisions contributed to the Civil Rights Movement’s use of direct action tactics in the 1960s. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. believed that lawsuits were not the right strategy for the movement, stating that “whenever it is possible, we want to avoid court cases in the integration struggle.” Similarly, the major organizations of the Civil Rights Movement all rejected using lawsuits to create social change. Instead, Civil Rights activists used peaceful protest methods, such as marches, sit-ins and Freedom Rides.

While there was a delay between Brown and the civil rights action it demanded, the decision marked a new era for the Court. Brown was the first of several cases decided under Chief Justice Warren that became landmarks in protecting individual rights and freedoms. Loving v. Virginia (1967) declared laws prohibiting interracial marriage unconstitutional. Mapp v. Ohio (1961), Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966) protected the rights of the accused. In Baker v. Carr (1962), the Court decided it was appropriate for the Court to review state redistricting plans, which indirectly allowed it to protect voting rights. These cases, along with Brown, all followed a trend of recognizing and protecting individual and civil rights.

Impact

The Court decided Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The federal government gradually took action to support the Court’s decision. State resistance, however, perpetuated school segregation. In 1979, more than two decades after Brown’s original ruling, the case was reopened regarding the children of Linda Brown Smith, the original plaintiff. Smith, along with a larger group of Black parents, claimed the Topeka, Kansas school district failed to desegregate schools after Brown.

Even if a state technically complied with Brown, residential housing patterns across the country meant many neighborhoods were racially segregated. Children are typically assigned to a neighborhood school, so in many instances the decision had little impact on school demographics. As a result, some district courts assumed responsibility for integrating schools. During the 1960s and 1970s, they used methods like assigning teachers, establishing racial quotas, and busing students outside of their neighborhood. These tactics were controversial. When the city of Charlotte, North Carolina challenged “forced busing,” the Supreme Court’s opinion in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1970) stated that busing was a legitimate way to integrate schools. Four years later, court-ordered busing in Boston, Massachusetts prompted protests from white residents. Ultimately, many of those families chose to leave the city. In 1970, white students made up 60 percent of Boston schools. By 1975, they composed 15 percent.

Even today, the work of Brown remains incomplete. A report from the US Government Accountability Office found that over 33 percent of students in the 2020-2021 school-year attended a school where more than three-quarters of the students were of a single ethnicity–showing that de facto segregation still exists. Despite the case’s difficulties and shortcomings, Brown v. Board of Education was a momentous decision that marked the beginning of an era of Civil Rights advocacy.

Discussion Questions

- Why was it difficult for the Supreme Court to enforce its decision in Brown v. Board of Education?

- In Brown II, the Court ordered states to implement Brown I “with all deliberate speed.” Why didn’t the Court provide more specific guidelines?

- Evaluate President Eisenhower’s response to state violations of the Supreme Court’s Brown decision.

- Which action by the federal government was the most successful in achieving desegregated schools? Why?

- Why do you think that civil-rights activists wanted to avoid using lawsuits as a method of activism?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Justin Driver for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Connato, Vincent. “The Controversy over Busing.” Bill of Rights Institute. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-controversy-over-busing.

Driver, Justin. Supremacies and the Southern Manifesto, 92 TEX. L. REV. 1053 (2014).

Gordy, Sondra. “Lost Year” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. 30 August 2023. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/lost-year-737/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20Lost%20Year%E2%80%9D%20refers%20to,an%20effort%20to%20block%20desegregation.

Hitchcock, William H. The Age of Eisenhower. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018.

“K-12 Education: Student Population Has Significantly Diversified, but Many Schools Remain Divided Along Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Lines.” U.S. Government Accountability Office. June 16, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104737.

Powe Jr., Lucas A. The Warren Court and American Politics. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000.

Rosenberg, Gerald N. “African American Rights After Brown.” Journal of Supreme Court History 24:2 (1999)

Urofsky, Melvin I. The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, California: ABC Clio, 2001.