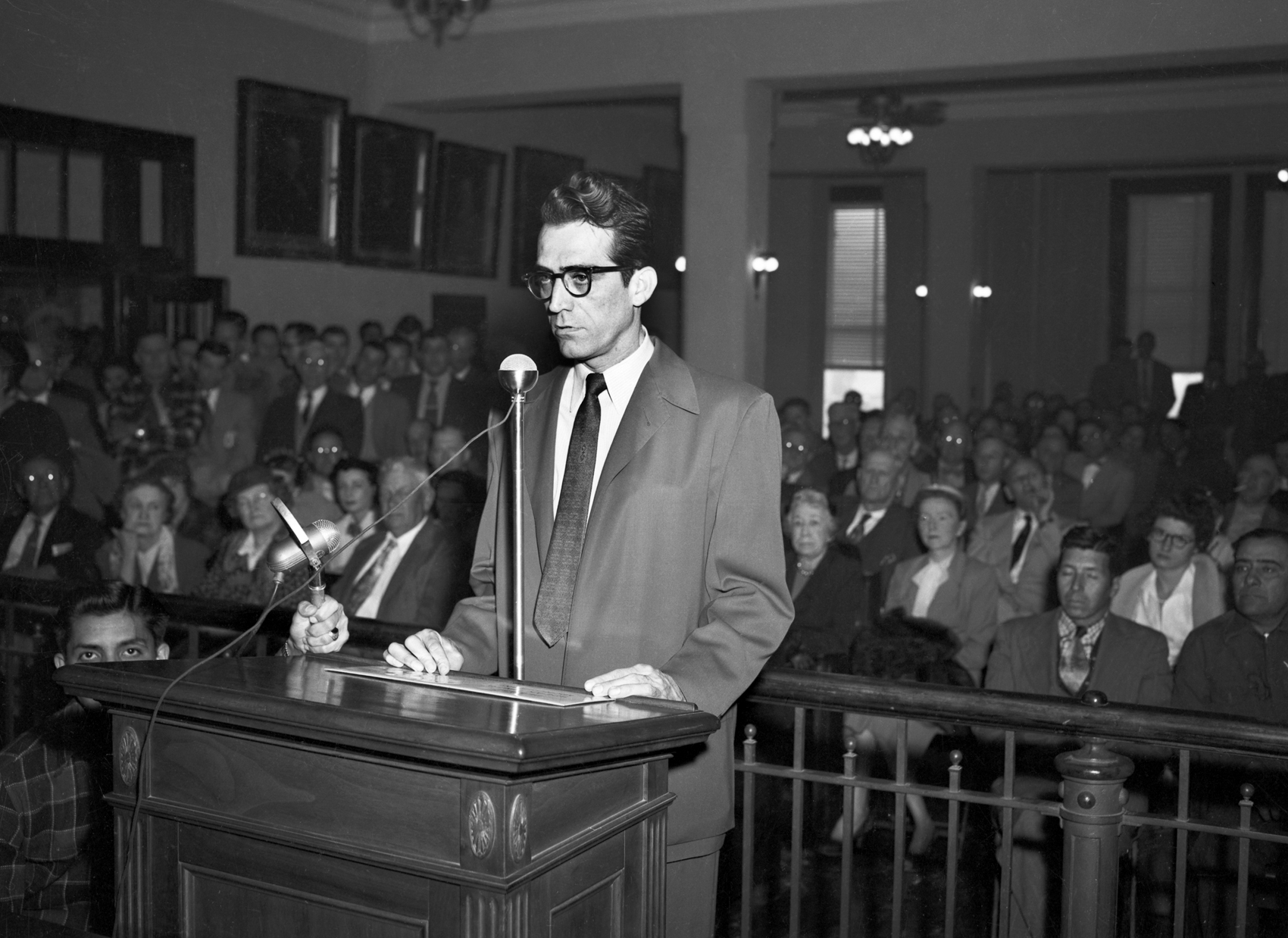

Gus Garcia

Life Story: 1915-1964

The charismatic attorney who fought for civil rights and worked with the first Mexican-American legal team to argue before the Supreme Court.

Background

Gustavo “Gus” Garcia was born July 27, 1915 in Laredo, Texas. The son of ranchers Alfredo and Maria Teresa (Arguindegui) Garcia, Gus grew up in San Antonio attending public and Catholic schools. He became the first valedictorian of the mostly-white Thomas Jefferson High School in 1932 and was the first Latin American to earn a scholarship to the University of Texas. While in college, he became the school’s first Mexican-American debate team captain. Under his leadership, the team never lost a match. He graduated with honors in 1936, and stayed for two more years to complete his law degree.

Career

Gus passed the bar in 1938 and spent the next four years as assistant district attorney in Bexar County and the city of San Antonio. Outside of work, Gus volunteered as a legal advisor to the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), a civil rights organization. In 1941, World War II put this work on hold. Gus was drafted as a First Lieutenant into the United States Army and was stationed in Japan as a judge advocate until 1945. When he returned home, he contributed to the creation of the United Nations.

After the war, Gus returned to private practice and advocacy work with LULAC. His natural charisma and his eloquence in both Spanish and English made him a strong and popular advocate for the Mexican-American community. Since the United States acquired the territory of Texas in 1848 after the Mexican-American War, people of Mexican descent in the state were legally classified as “white,” but received second-class treatment.

Much of Gus’s advocacy targeted unequal schooling for Mexican-American children in Texas. In Texas, many schools remained segregated, regardless of the legal “white” status of Mexican Americans. In some areas of the state, students of Mexican descent were either refused schooling or undereducated. While working for the office of the Mexican Consulate General in San Antonio, Gus successfully argued that the school district in Cuero, Texas must close its Mexican-only school. Then, Gus partnered with attorney Carlos Cadena and LULAC in Delgado v. Bastrop ISD (1948). The team represented 20 families that did not want their children to be segregated in public schools. Gus’s argument focused on the lack of equitable facilities, instruction, and services for Mexican-American students. The US District Court for the Western District of Texas agreed with the argument and ordered the Bastrop school district to desegregate by September of 1949. Delgado was the first step towards ending de jure segregation of Mexican-American students in the Texas school system.

Garcia’s work history was rooted in service to his community. He used to say, “I’d rather soak in the applause than make a fat legal fee.” From 1948 to 1952, Gus served on the San Antonio Independent School District Board of Education. He was the first Mexican American elected to the board. At the same time, he continued to provide legal services for Mexican-American civil rights organizations LULAC and the American GI Forum. As a member of a multitude of local organizations like the American Council of Spanish Speaking People, the Texas Council on Human Rights, and the Mexican Chamber of Commerce, the University of Texas’s Alba Club recognized his efforts for his community and named him “Latin of the Year” in 1952.

Supreme Court Advocacy

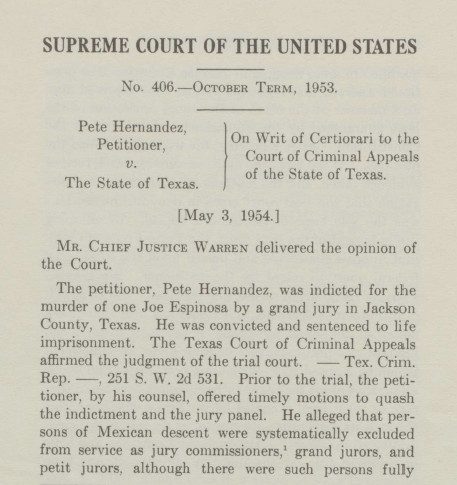

In Hernandez v. Texas (1954), Gus and Carlos Cadena served on the first Mexican-American legal team to argue in front of the Supreme Court. In this case, Pedro “Pete” Hernandez, a Mexican-American migrant cotton picker, shot and killed Caetano “Joe” Espinoza after a verbal altercation on February 23, 1951. Pete’s family hired Gus to be part of the legal defense team. In Texas, de facto segregation existed throughout schools, businesses, and everyday life. This motivated Gus to take the case on a pro bono basis. Though there was little to dispute around Pete’s guilt, Gus believed that the jury composition at Hernandez’ sentencing violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. There was not a single person of Mexican descent on the jury who decided Hernandez’ fate. In fact, no one of Mexican descent had served on a jury in Jackson County for the last 25 years.

Gus argued that Jackson County systematically excluded Mexican Americans from jury service. This prevented Hernandez from receiving a fair and impartial jury of his peers, a right guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment. While arguing Hernandez’ initial case in the Jackson County courthouse, Garcia attempted to enter a bathroom marked “Whites Only.” He was directed to another restroom labeled “Blacks Here and Hombres Aquí (men here).”

After multiple appeals, the Supreme Court heard the case in 1952. Though the Court typically adheres to strict time limits for oral arguments, Chief Justice Earl Warren allowed Gus an extra 16 minutes in front of the Court to address his point. Co-counsel Carlos Cadena later described watching Gus deliver his closing arguments: “I argued in front of the justices for 40 minutes and Gus summed it up. I’ll never forget it, he used every device in the lawyer’s bag of tricks, from easy facility of speech and legal sharpness to anger, sarcasm, the soft voice, dramatic pause and deft touch of humor.”

In a unanimous decision, the Court reversed Hernandez’ conviction and granted him a retrial. Chief Justice Warren wrote for the Court that “the exclusion of otherwise eligible persons from jury service solely because of their ancestry or national origin is discrimination prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Hernandez v. Texas marked the first time the civil rights of Mexican Americans were asserted at the highest judicial level.

Legacy

Though Gus was a gifted attorney, he privately struggled with alcoholism and mental health. He married three times and fathered two children, but became estranged from his family. After admission to the hospital in 1955 for alcoholism, he received fewer invitations to LULAC and GI Forum events. Then, in 1960, eight lawyers from San Antonio sought to have Gus disbarred after he wrote multiple bad checks. He was not disbarred, but his license to practice was suspended for the next two years. Unfortunately, neither his career nor his physical health recovered. Gus suffered a seizure induced by liver failure and died on June 3, 1964 at just 48 years old. On his death certificate under “race or color,” the coroner wrote “white.”

Gus Garcia’s advocacy created a lasting impact for the Mexican-American community. From the time he was a student, Gus broke through barriers and served as a representative for his underserved community. His dedication to achieving equality for Mexican Americans in public schools and in the judicial system directly led to the Supreme Court acknowledging that Mexican Americans, and by extension all racial groups, are protected under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Discussion Questions

- How were Mexican Americans treated in Texas after the Mexican-American War?

- When something is ironic, it means that it happens in a way that is the opposite of what you would expect. Why was it ironic that Gus was not allowed to use the “whites-only” bathroom in the Jackson County courthouse?

- How did Gus Garcia’s work advance civil rights for Mexican Americans?

Extension Activities

-

In 2013, Texas recognized “Gus Garcia Day” on his birthday, July 27. Write a letter to Congress explaining why you think we should celebrate “Gus Garcia Day.”

-

Create a proposal for a three-episode docuseries about Gus Garcia and his work on the Hernandez case. Use the Hernandez v. Texas (1954) case summary for additional information.

-

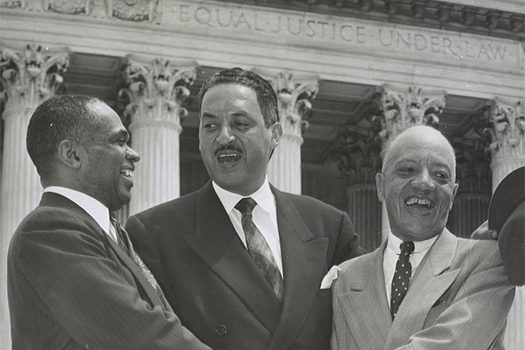

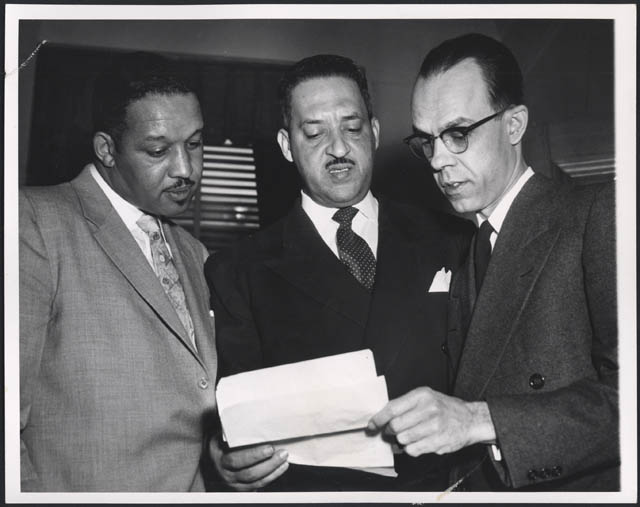

Compare and contrast how Gus Garcia and Thurgood Marshall advocated for equal opportunities in schools. Use the resource “Thurgood Marshall as an Advocate” for additional information.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Ignacio Garcia for his review and feedback.

“Funeral Set for Noted Latin Lawyer.” Corpus Christi Caller-Times. June 5, 1964.

Garcia, Gustavo C. “Speech by Gus C. Garcia – 1952-01-29.” The Portal to Texas History. Last modified August 20, 2013. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth248890/.

García, Ignacio M. White but Not Equal : Mexican Americans, Jury Discrimination, and the Supreme Court. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009.

Orozco, Cynthia E. “Garcia, Gustavo C. (1915-1964).” Handbook of Texas. Last modified October 27, 2020. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/garcia-gustavo-c.

Valle, Gabriel. “A Hero Forgotten: Gus Garcia and the Litigation of Hernandez v. Texas (1954).” Journal of Supreme Court History 48, no. 1 (2023): 31-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/sch.2023.a897346

Featured image: Gus Garcia, legal advisor for the American G.I. Forum visiting the White House. , 1952. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007684155/.