Civil Rights Cases (1883)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to be unconstitutional and paved the way for Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Jim Crow segregation.

Background

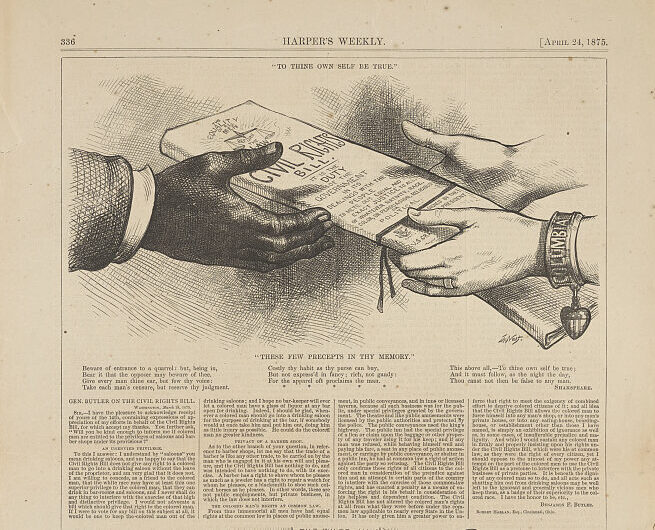

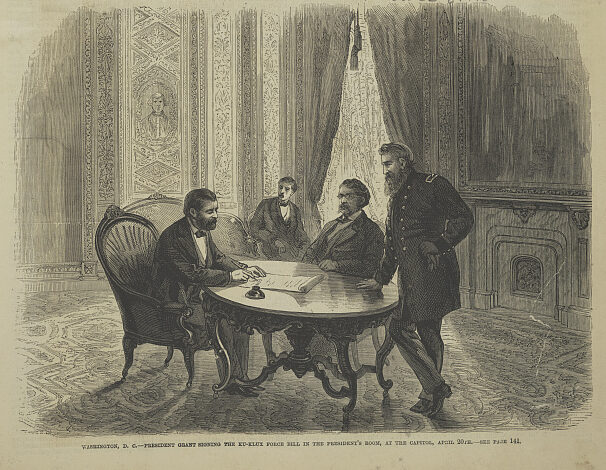

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the Reconstruction Amendments, combined with other federal programs and legislation, sought to establish and protect the civil rights of newly-freed African Americans. Ten years into Reconstruction, on March 1, 1875, Congress passed “An Act to Protect All Citizens in Their Civil and Legal Rights.” The act, more commonly known as the Civil Rights Act of 1875, strengthened the Thirteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment by making racial discrimination in public accommodations (not including schools) illegal. Under this law, “citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude” were “entitled to the full and equal enjoyment” of transportation, hotels, theatres, and other facilities.

The act quickly generated several test cases across the country. Black citizens in both Northern and Southern states went to theatres, hotels, and other public spaces to see if and how the law would be enforced.

Facts

Between 1875 and 1880, five of these test cases moved through the district courts of Kansas, California, Missouri, New York, and Tennessee. Each plaintiff claimed the defendant violated the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and by extension, their Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. All were denied accommodation either in a hotel, theatre, or railroad car. The defendants, on the other hand, challenged the law’s constitutionality, questioning whether or not Congress had the authority to regulate private actions. The Supreme Court of the United States heard the five appeals combined as the Civil Rights Cases in 1883.

Issue

Did Congress have the authority to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1875 under the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments?

Summary

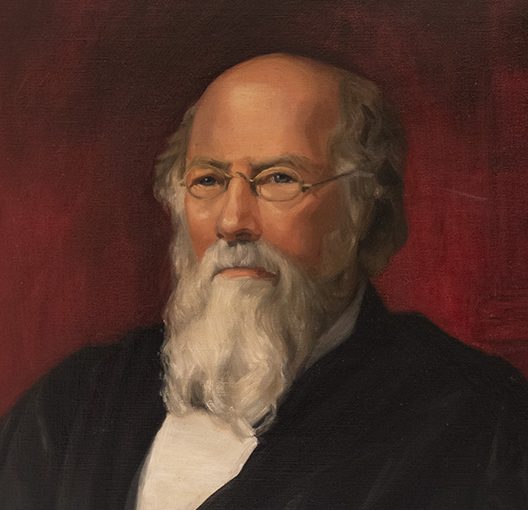

In the 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In the Court’s majority opinion, Justice Joseph P. Bradley wrote that neither the Thirteenth nor Fourteenth Amendment authorized Congress to outlaw private discrimination. The Court’s narrow interpretation on these amendments reflected a prevailing discriminatory and prejudicial thinking of the time. Regarding the Thirteenth Amendment, he challenged the connection between slavery and the denial of public accommodations. According to Justice Bradley, “mere discriminations on account of race or color were not regarded as badges of slavery,” so Congress could not use the Thirteenth Amendment to justify the Civil Rights Act. Furthermore, the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to private actions by individuals or businesses. The majority opinion held that the amendment could only be used against “state actions,” so the Civil Rights Act’s sweeping declaration that all persons regardless of race were “entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations…and places of public amusement” overstepped Congressional authority. The Court declared the law unconstitutional.

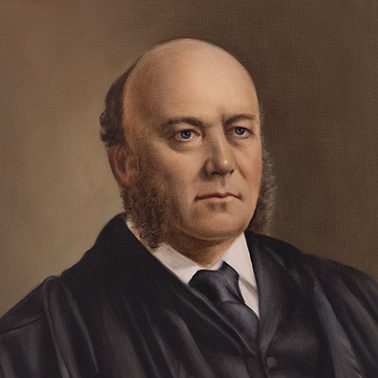

Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented, stating “there cannot be, in this republic, any class of human beings in practical subjugation to another class.” He argued for a broader interpretation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments and explained that private businesses, like railroads, served a public function. Thus, he held the view that Congress had the authority to enforce regulations even though the businesses were privately owned.

Precedent Set

By holding that the amendments applied only to state actions, not the actions of private individuals or businesses, the decision limited the scope of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court cited the Civil Rights Cases as precedent in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which legalized racial segregation and led to the creation of Jim Crow laws.

Additional Context

Nearly two decades after the end of the Civil War, the nation remained divided over issues of race and civil rights. In response to the Civil Rights Cases, 10 Northern states passed their own laws using the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Activists condemned the Supreme Court’s decision in mass meetings across the country. In a speech in Washington, D.C., abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass stated the decision “inflicted a heavy calamity upon seven millions of the people of this country, and left them naked and defenceless against the action of a malignant, vulgar, and pitiless prejudice.” Meanwhile, the same year as the Civil Rights Cases, the Supreme Court upheld an Alabama anti-miscegenation law in Pace v. Alabama. The following year, Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, won the presidency and, together with Congress, ended federal efforts to enforce voting rights in the South.

When Plessy v. Ferguson legalized racial segregation based on the “separate but equal” principle in 1896, Justice Harlan, again, was the lone dissenter. Echoing his dissent from the Civil Rights Cases, he argued “in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens.” Eventually, the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy opinions were overturned and the position Justice Harlan expressed in his dissents became the law of the land. Ultimately, Congress did not enact a new federal civil rights law prohibiting racial discrimination in public accommodations until 1964, and this ban rested not on the Fourteenth Amendment but on the Commerce Clause.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Waite

-

Miller

-

Field

-

Bradley

-

Harlan

-

Matthews

-

Woods

-

Gray

-

Blatchford

-

Majority Opinion

Joseph P. BradleyRead More CloseWhen a man has emerged from slavery, and, by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen or a man are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.

-

Dissenting Opinion

John Marshall HarlanRead More CloseIf the constitutional amendments be enforced according to the intent with which, as I conceive, they were adopted, there cannot be, in this republic, any class of human beings in practical subjection to another class with power in the latter to dole out to the former just such privileges as they may choose to grant. The supreme law of the land has decreed that no authority shall be exercised in this country upon the basis of discrimination, in respect of civil rights, against freemen and citizens because of their race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the Civil Rights Act of 1875 generated “test cases”?

- Why do you think the Supreme Court decided to hear the five civil rights cases together instead of hearing each one individually?

- Why did the Supreme Court decide the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional?

- What were the short and long term effects of the Civil Rights Cases?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and professor of government G. Grier Stephenson for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Nast, Thomas, Artist. “To thine own self be true” A privilege? / Th. Nast. United States, 1875. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010644169/.

Brandwein, Pamela. “A Lost Jurisprudence of the Reconstruction Amendments.” Journal of Supreme Court History 41, no. 3: 329-346 (2016).

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

Franklin, John Hope. “The Enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.” 6 Prologue 225 (1974). 226-234. https://studylib.net/doc/8205613/the-enforcement-of-the-civil-rights-act-of-1875.

Ranney, Joseph A. “‘This Law, Though Dead, Did Speak’: The Civil Rights Cases and their Unforeseen Aftermath.” Journal of Supreme Court History 49, no. 1: 8-25 (2024).

Sinha, Manisha. The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2024.