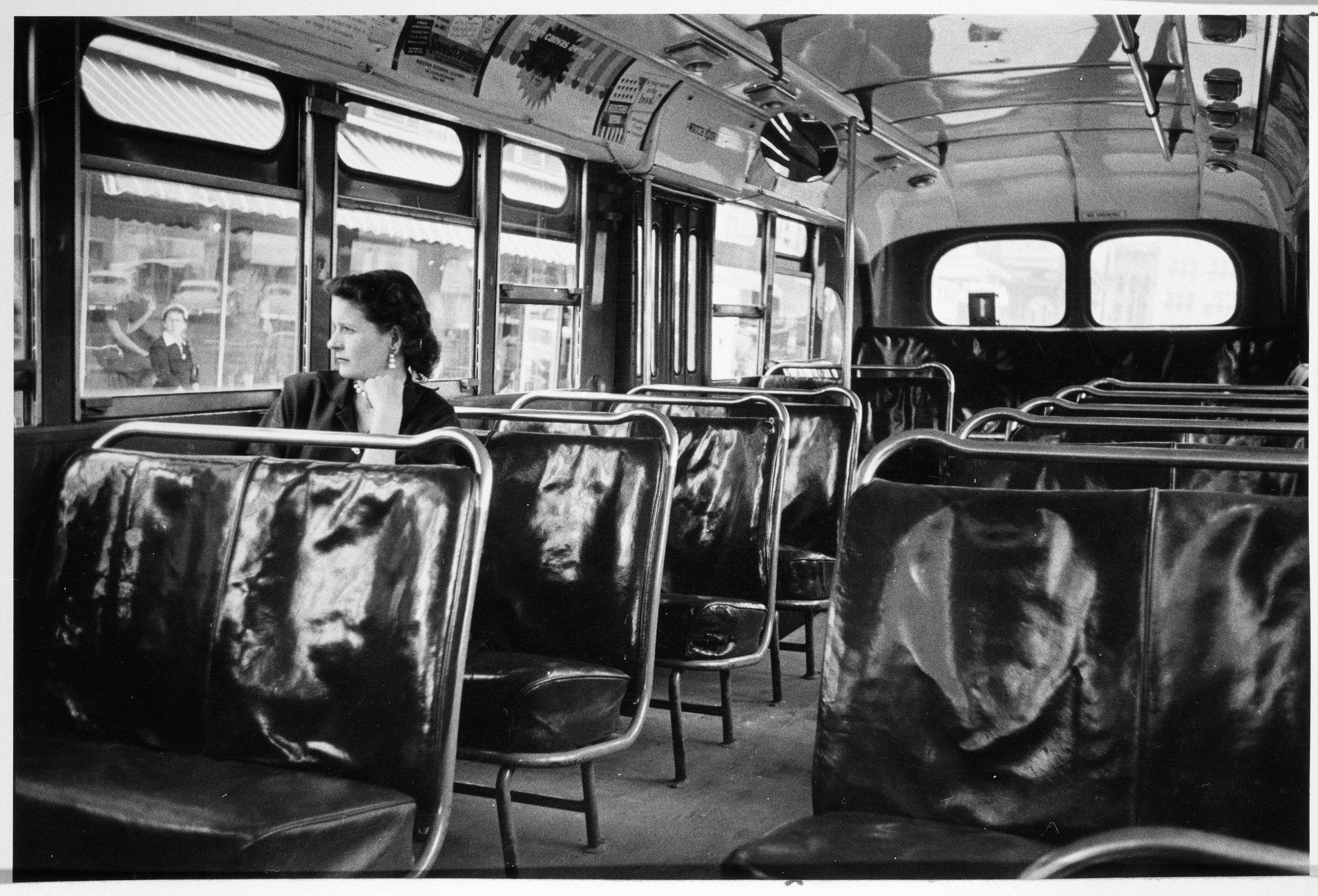

Browder v. Gayle (1956)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court’s affirmation of a district court decision to outlaw segregated bussing in Montgomery, Alabama that overturned Plessy v. Ferguson.

Background

After the Supreme Court upheld the legality of state-mandated racial segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), some states created Jim Crow laws. Even after the Supreme Court functionally overturned Plessy’s “separate but equal” doctrine in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), some Southern states avoided desegregating schools and public facilities, and de facto segregation persisted in the North. The Brown decision was unclear about whether state-mandated segregation was unconstitutional in all spheres of life, or just in schools. As a result, many states and localities enforced Jim Crow long after Brown. Across the nation, civil rights activists and organizations challenged the constitutionality of these laws.

One of these organizations was the Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery, Alabama. On May 24, 1954, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson wrote to the city’s mayor, W.A. Gayle, asking for fair treatment for African Americans on city buses. The demands of the WPC fell short of desegregation; they hoped for smaller improvements, such as more stops in Black neighborhoods and the hiring of Black bus drivers. Robinson’s letter also called for more courteous treatment of African Americans, such as that Black riders “not be asked or forced to pay fare at front and go to the rear of the bus to enter.” Her letter warned that plans for a bus boycott were in the works if the city failed to meet these demands.

The busing conditions did not change. Both Montgomery ordinances and Alabama statutes mandated segregation on bus lines and authorized motor transportation company employees to enforce the laws. On March 2, 1955, Montgomery police arrested 15-year-old Claudette Colvin after she refused to move to the back of the bus, the designated seating area for Black riders. She was the first person to be arrested for challenging Montgomery’s bus segregation laws. Initially, the WPC considered Colvin’s arrest the perfect occasion for a city-wide bus boycott; however, they ultimately decided against using her case. Colvin recalled that Black leaders wanted someone “who could rally the adults,” and she was viewed as an “emotional” teenager. Additionally, soon after the arrest she found out she was pregnant, and the NAACP did not want a pregnant teenager to be the face of the cause because, Colvin said, “they’d be talking about the pregnancy more so than they would be talking about the bus boycott.” Still, Colvin inspired others to take action. Three other women were arrested in the spring for the same offense: Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith. On December 1, nine months after Colvin’s arrest, police arrested Rosa Parks for violating the bus segregation laws. Parks, the secretary of the local NAACP, was the perfect woman to represent the movement. Robinson and the WPC immediately distributed flyers announcing a city-wide bus boycott by African Americans. The boycott officially began on December 5, 1955. Black people walked, carpooled, or took cabs, which had even agreed to a reduced fare. Browder, who worked with a cab company, used her cars to help boycotters.

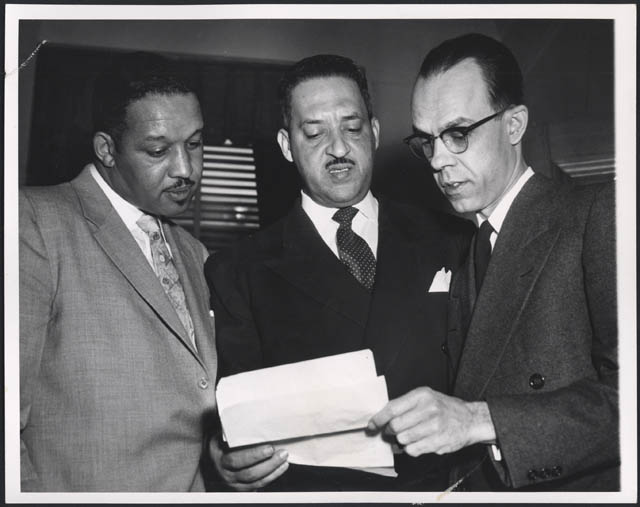

The WPC and its collaborator, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., only intended for the boycott to last for a day. After 5,000 people attended a rally that night, movement leaders decided to continue the boycott. On December 13, Parks, King, and local civil rights attorney Fred Gray met with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to ask for the organization’s support. The NAACP agreed to help.

Facts

On February 1, 1956, Gray filed a federal court action on behalf of the women arrested for refusing to comply with bus segregation—Colvin, Browder, McDonald, and Smith—with Browder as the lead plaintiff. He chose not to include Parks in the suit (he had already filed an appeal for her separately).

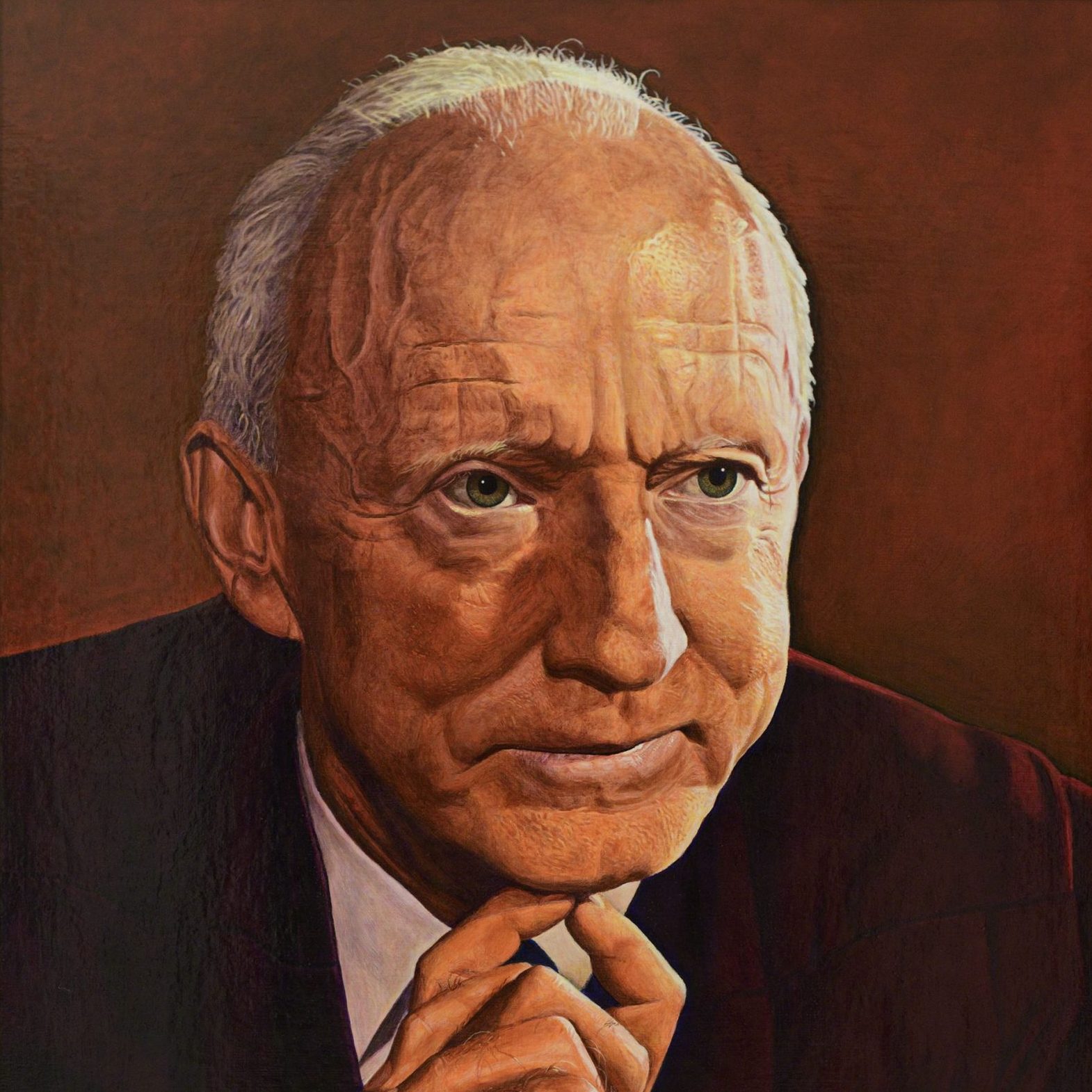

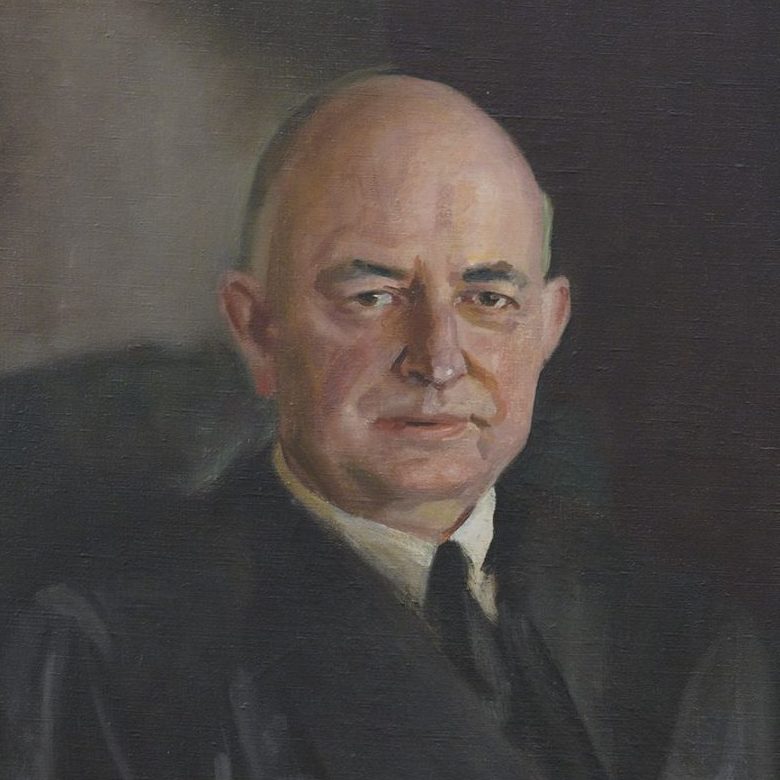

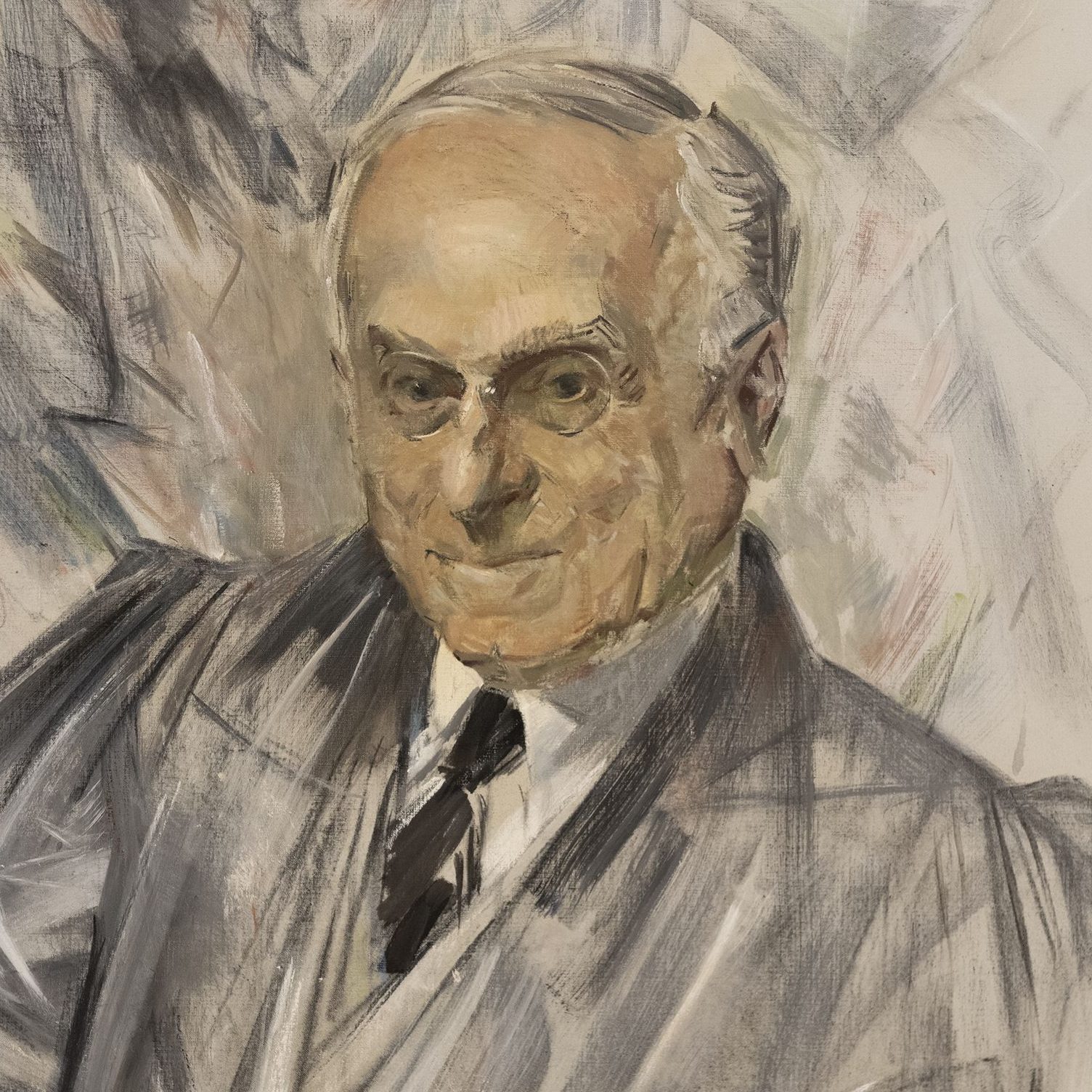

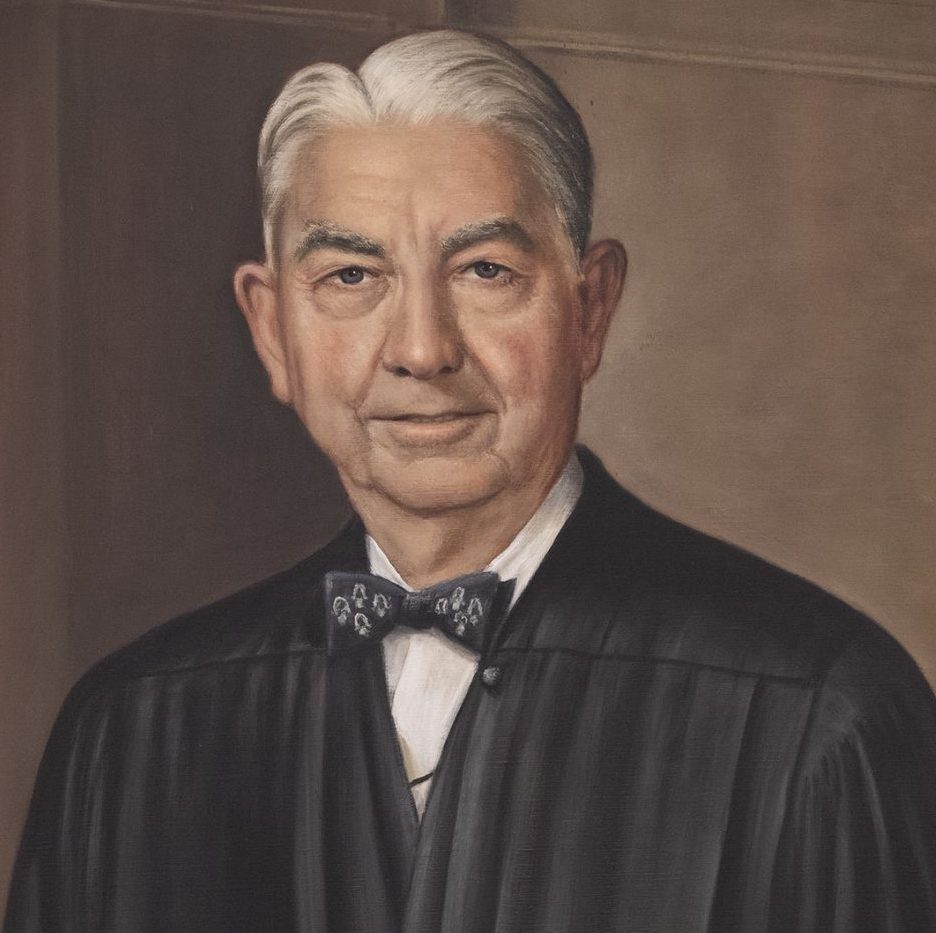

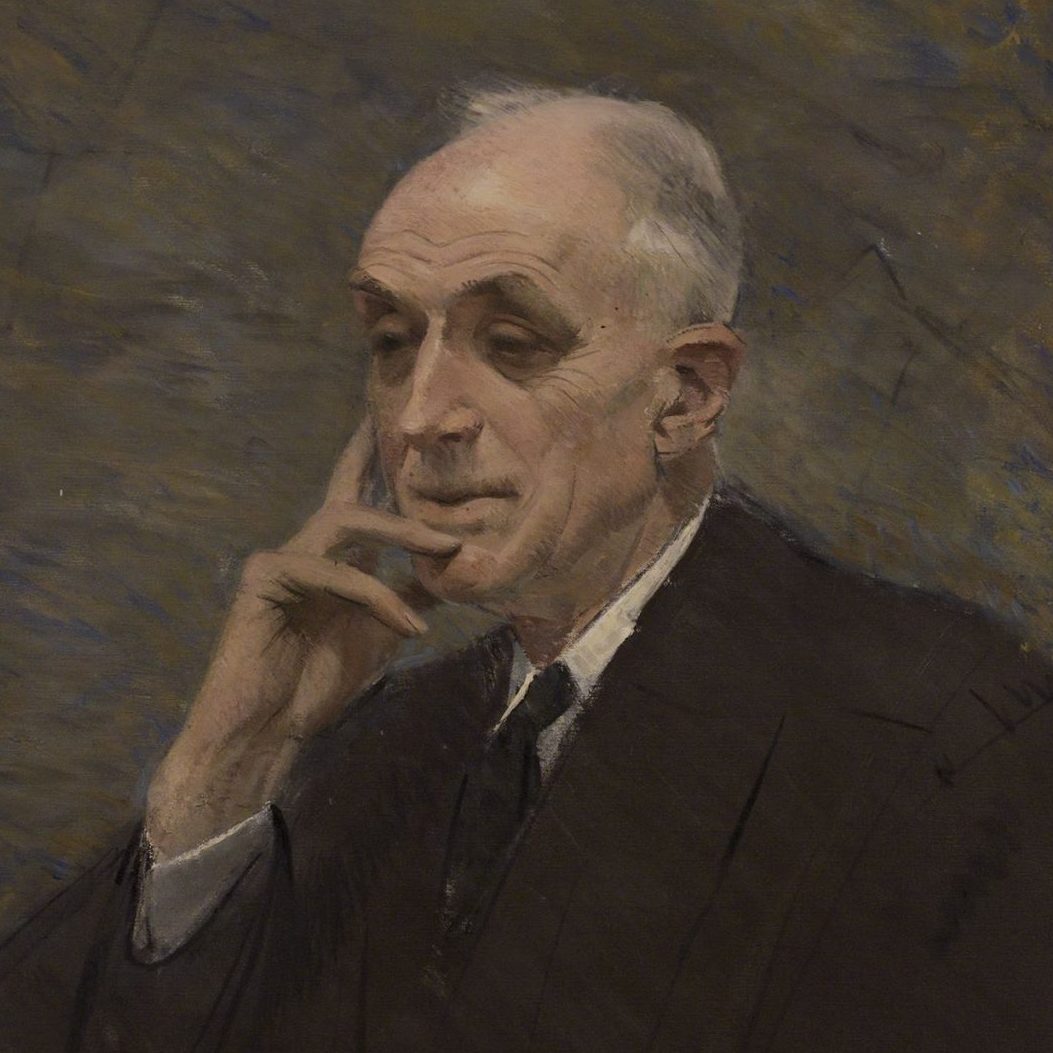

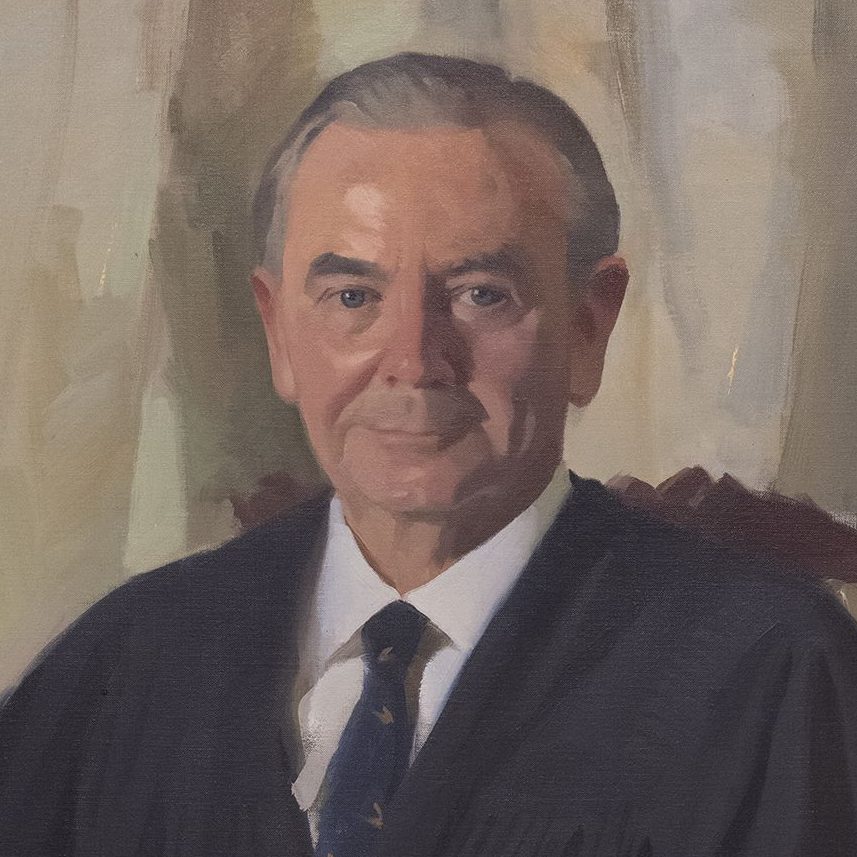

The lawsuit sued Montgomery public officials, including the Board of Commissioners (where Mayor Gayle served), and the bus company, Montgomery City Lines, Inc., claiming the bus segregation laws they enforced were unconstitutional. Because the case challenged a state statute, a three-judge federal district court heard the case. The panel included judges Richard Rives, Frank M. Johnson, and Seybourn Lynne.

Issue

Did the Alabama law and Montgomery ordinance mandating segregated busing violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution?

Summary

On June 5, 1956, the three-judge court ruled that the statutes violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the majority opinion, Judge Rives, joined by Judge Johnson, explained how the Supreme Court had dismantled the “separate but equal” principle established by Plessy. He reasoned that the Court’s education decisions, especially Brown, “weakened…and then destroyed the separate but equal concept.” Subsequent opinions outlawing segregation in recreational facilities and other public spaces had further diminished the scope of Plessy. Rives concluded that “that the separate but equal doctrine can no longer be followed as a correct statement of the law.” Judge Lynne dissented. He argued that Brown only applied to schools and therefore “it left unimpaired the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine in a local transportation case.”

On June 19, 1956, the court ordered Montgomery to stop enforcing all Jim Crow laws. The state appealed the case to the Supreme Court, so the desegregation order was suspended pending appeal. On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s decision, holding that the Alabama and Montgomery laws violated the U.S. Constitution. The Court did not hear oral argument or issue written opinion in this case. Rather, after Brown, which was controversial, the Court had decided to extend its reasoning to other Jim Crow laws in terse, per curiam opinions. The Court refused to grant the state’s request for a rehearing. On December 20, after Montgomery officially complied with the Court’s ruling, the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended, 381 days after it began.

Precedent Set

Browder v. Gayle led to the immediate integration of Montgomery buses. By affirming the lower-court decision, the Supreme Court effectively overturned the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. It clarified the Brown decision by extending the bar on “separate but equal” to all aspects of public life.

Additional Context

Browder occurred during a major turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. Eighteen months earlier, the Court had outlawed school segregation in Brown and then had quickly extended that ruling to other public settings. Then, in August 1955, white supremacists in Mississippi murdered a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago, Emmett Till. His death brought new national attention to the Civil Rights Movement. When asked why she refused to give up her bus seat, Rosa Parks replied, “I thought of Emmitt Till, and I couldn’t go back.”

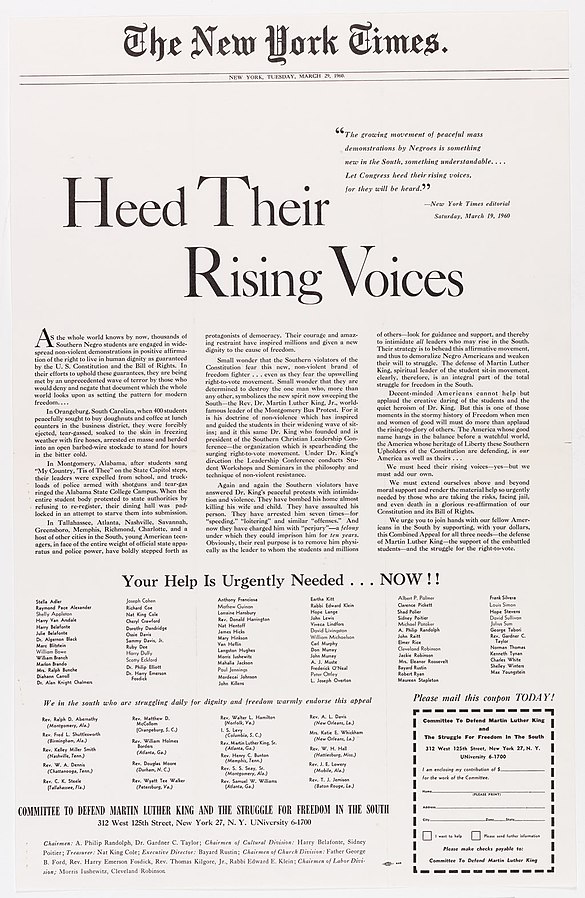

Browder and the bus boycott also marked a new strategic approach in the movement. Until then, civil rights leaders relied on litigation to create change. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, challenged local segregation laws in court. However, after Brown, segregated states attacked the NAACP. Alabama banned the NAACP from the state for 8 years. In other parts of the South, the NAACP also came under legal and economic attack. New leaders and organizations emerged to fill this void, including Dr. King, and new direct action tactics were employed as a supplement, or even an alternative, to litigation. Unlike litigation, which required money and lawyers, anyone could participate in a boycott, a march, or a sit-in.

Decision

The Court issued a per curiam opinion in favor of Browder.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Warren

-

Black

-

Reed

-

Frankfurter

-

Douglas

-

Burton

-

Clark

-

Harlan II

-

Brennan

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think that the WPC chose to ask the city for smaller changes instead of bus desegregation?

- Was a boycott an effective strategy for the WPC and the MIA? Why or why not? Explain.

- Federal judges are appointed for life. How do you think that impacted the ruling in Browder?

- How did the Court’s decision in Browder impact the course of the Civil Rights Movement?

Extension Activities

-

Make a Connection

How did reactions to Brown v. Board of Education (1954) influence the Court’s decision to issue a per curiam opinion in Browder? Use the resource Brown as the Beginning for additional information.

-

Create a Historical Marker

Create a historical marker commemorating Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Mary Louise Smith, or Susie McDonald. A historical marker is a sign that marks where an important event took place and why it was important.

Sources

Special thanks to the Johnson Institute and to scholar and law professor Michael Klarman for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Bennett, Brad. “Journey to Justice: Celebrating the 65th Anniversary of Montgomery Bus Boycott that Sparked Civil Rights Movement.” Southern Poverty Law Center. 4 December 2020. https://www.splcenter.org/news/2020/12/04/journey-justice-celebrating-65th-anniversary-montgomery-bus-boycott-sparked-civil-rights.

Colvin, Claudette. Interview by Matthew Bannister. The Outlook Podcast. BBC. 22 February 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p05z1929.

Moore, Logan J. “Browder v. Gayle.” Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. Institute. 2020.

W.C. Patton, NAACP Alabama Field Secretary, letter to NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins, and Director of Branches Gloster B Current. 19 December 1955.

Robinson, Jo Ann Robinson. Letter to Honorable Mayor W. Gayle. May 21, 1954. https://historicalthinkingmatters.org/rosaparks/1/sources/19/index.html.

Sullivan, Patricia. Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: The New Press, 2009.

Tushnet, Mark V. Making Civil Rights Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1936-1961. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Featured image: Photograph of Montgomery, Alabama Bus Boycott; 1956. Records of the U.S. Information Agency via the National Archives: DocsTeach. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/montgomery-bus.