The Election of 1876

Significant Event

The disputed presidential election that many scholars claim marked the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction.

Background

On November 7, 1876, less than 12 years after the Civil War ended, the newly reunited states went to the polls to elect a new president. Although the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited states from discriminating by race when making voting laws, massive fraud took place in many former Confederate states. As a result, the 1876 presidential race did not end on Election Day. Instead, it developed into a national crisis.

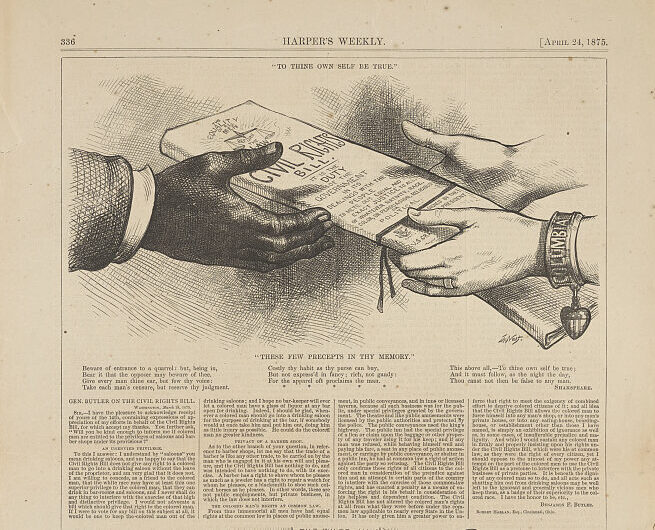

After the Civil War, the country entered an era of Reconstruction. Between 1865 and 1877, three new constitutional amendments, combined with other federal programs like the Freedmen’s Bureau, created more educational, professional, and political opportunities for formerly enslaved Black Americans. As part of Reconstruction, the federal government required all former Confederate states to ratify the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments in order to rejoin the union. Some states were also required to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment.

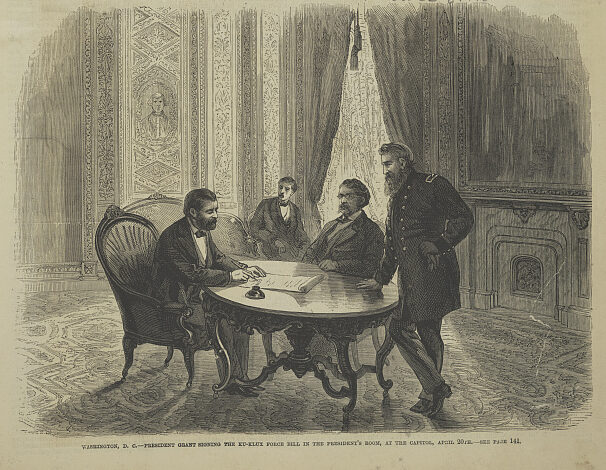

Reconstruction was effective for a brief period of time. After the Fifteenth Amendment gave Black men the right to vote, former Confederate states became representative of their populations. Nearly 2,000 Black men served in elected positions during this time. By the mid-1870s, however, white conservative Democrats regained control in all Southern states but Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan used violence and intimidation to restore white supremacy and reverse Reconstruction’s progress. To protect Republican voters and enforce Reconstruction laws, President Ulysses S. Grant stationed federal troops in the former Confederacy. Implementing martial law further increased political tensions between the parties. By 1876, there was extreme racial polarization in almost all former Confederate states.

The Election

No one disputes that Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, the governor of New York, won the popular vote in the 1876 presidential election. Whether Tilden also gained a majority of the electoral votes, however, was contested. Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate challenged the votes in four key states: Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon. Since these states were governed by Republican majorities, Hayes and other Republicans suspected that Democrats had tampered with the ballots, particularly in districts with a heavy African-American population. Republicans alleged that the popular vote counts in these states were tainted by ballot stuffing, ballot stealing, and intimidation of Black voters. Between the four states, 20 electoral votes were contested. If Hayes was given all 20 of those electoral votes, he would win the Electoral College by one vote.

The Reconstruction state governments investigated the allegations. In the following weeks, they threw out the vote in entire districts for polling misconduct. The revised vote counts gave Hayes clear majorities in the popular vote in all four states. The Democratic Party, however, believed the recount was unfair and corrupt. Tilden and his allies refused to accept the new count. As a result, both parties claimed that their candidate won the popular vote in the four contested states. They each certified their results to the Electoral College, whose electors were responsible for casting the final votes in the presidential election.

The Electoral Commission

To settle the dispute, President Grant signed a law creating a bipartisan election committee composed of 10 members of Congress and four Supreme Court justices. They deliberated sitting at a table set up inside the Supreme Court’s Courtroom in front of the bench. The commission was evenly split among party lines. To avoid a deadlock, the four Supreme Court justices were tasked with selecting a fifth justice. This justice would have the tie-breaking vote on the commission. They originally chose Justice David Davis, who at that time had no clear party affiliation, but Davis preferred to seek a Senate seat in Illinois. The commission then asked Justice Joseph P. Bradley, who was considered to be one of the least partisan members of the Supreme Court. Justice Bradley agreed to serve, knowing that he would be choosing the next president and that his vote would be criticized by half the country.

After considerable deliberation, Justice Bradley voted with the commission’s Republicans on all issues. As a result, the 20 disputed electoral votes were awarded to Rutherford B. Hayes, giving him the number needed to win the election. He won by a single electoral vote.

Impact

After his inauguration on March 5, 1877, President Hayes withdrew the federal troops stationed in the South, symbolically ending Reconstruction. Some believe this action was part of an unwritten deal orchestrated between Republicans in Congress and Southern leaders known as the Compromise of 1877. Republicans may have won the presidency by a controversially close margin, but the system hastily created to decide the election resulted in a peaceful transfer of power. In 1887 Congress passed legislation that changed how it would process disputed electoral votes to prevent a possible deadlock in the future.

Discussion Questions

- Why did Hayes’ campaign decide to dispute the original election results?

- Why did Congress decide to create an electoral commission?

- How did Justice Bradley impact the outcome of the election?

- How did the results of the Election of 1876 contribute to the end of Reconstruction?

- After popular vote and electoral votes are counted, Congress is responsible for certifying election results and making them official. The 1876 Election Commission met in the Supreme Court and included Supreme Court Justices in addition to members of Congress. Do you think this violates the principle of separation of powers? Why or why not?

Sources

Special thanks to scholars Mark Graber and Michael F. Holt for their review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured Image: Nast, Thomas. “A truce – not a compromise, but a chance for high-toned gentlemen to retire gracefully from their very civil declarations of war.” Harper’s Weekly. February 17, 1877. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/93510088/.

Corbett, Scott P., Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Toff Pfannenstiel, Sylvie Waskiewicz, and Paul Vickery. “16.4: The Collapse of Reconstruction.” U.S. History. OpenStax. Houston, TX: Rice University, 2014. https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/16-4-the-collapse-of-reconstruction.

Holt, Michael F. “The Contentious Election of 1876.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/contentious-election-1876.

Rehnquist, William H. Centennial Crisis: The Disputed Election of 1876. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

“The Supreme Court and the Presidential Election of 1876.” Supreme Court Historical Society. https://supremecourthistory.org/schs-supreme-court-1876-election/.