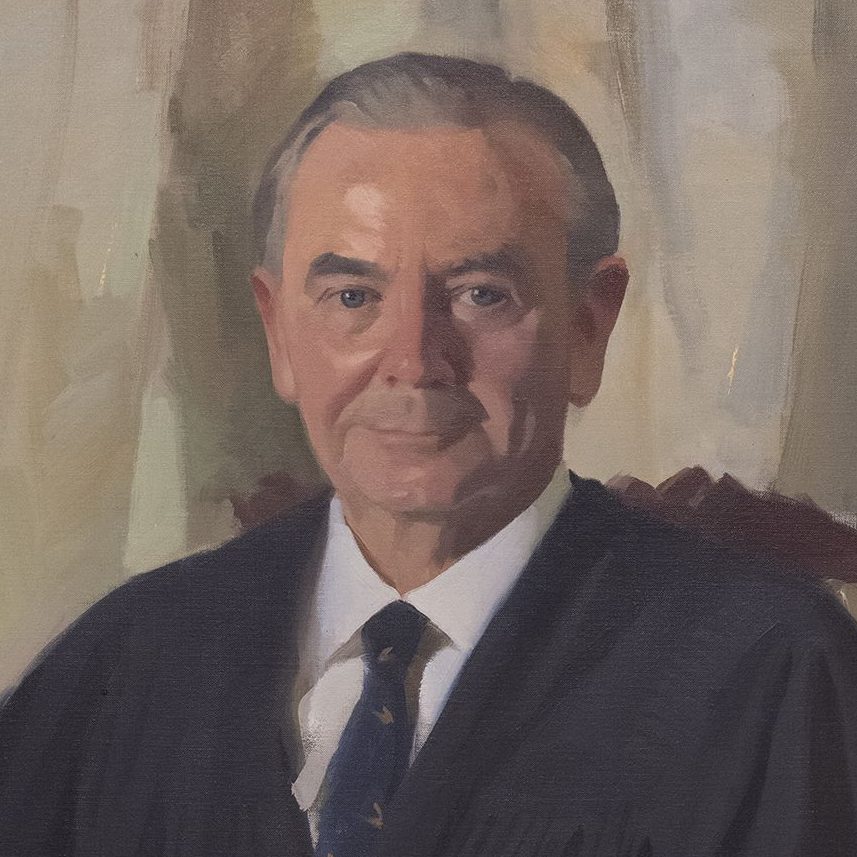

William J. Brennan Jr.

Life Story: 1906-1996

The first-generation American who served as an Army Colonel in World War II, became a reform-minded New Jersey judge, and was a consensus builder on the Supreme Court

Background

William “Bill” J. Brennan Jr. was born in Newark, New Jersey on April 25, 1906. Both of his parents immigrated from Ireland and had little formal education. The Brennans were avid readers and talked about politics at home with their children. His father, William “Bill” Brennan Sr., was a labor union leader and eventually became the Newark City Commissioner. He was a popular figure and when he died, more than 40,000 people came to see him lie in state at City Hall. His mother, Agnes Brennan, was a homemaker. Bill was the second of eight children.

The Brennans hoped their children would get the education they never had the opportunity to receive in rural Ireland. Bill had no trouble living up to his parents’ high expectations. He started school at age 5, and quickly became known as a bookworm. His academic success continued in high school. He maintained high marks, participated in several clubs, and worked an after-school job. Another part of Bill’s education was simply growing up with a dad in politics. Observing a labor leader up close showed him how government power could be used to both help and hurt individuals. Then, at age 15, Bill helped his dad campaign for city commissioner. The slogan was “a square deal for all, special privileges for none.” This idea would later be a major influence on Bill’s legal philosophy, which emphasized fairness and human dignity.

Bill’s dad encouraged him to study business in college—and not just any college. His parents had their hearts set on their first college-bound family member attending an Ivy League school. In 1923, when Bill applied to college, Catholic students typically attended church-affiliated schools. Ivy League schools were predominantly Protestant institutions, so at the time, attending one would help advance the family’s socioeconomic standing. His father’s push for a business major was also a sign of the times. The stock market boomed at the start of the Roaring Twenties, and he dreamed of Bill working as a Wall Street attorney.

Always heeding his father’s advice, Bill majored in finance at the University of Pennsylvania—an Ivy League school. While at Penn, he joined the Delta Tau Delta fraternity, earned the highest marks on his grade reports, and worked odd jobs over the summers. He also fell in love with his first wife, Marjorie Leonard, whom he knew from high school.

Bill graduated in 1928 and enrolled in Harvard Law School—a decision that would mean three years of living separately from his beloved Marjorie. She stayed home in Newark and worked for a newspaper while he went to Massachusetts. The couple wanted a formal commitment but knew their families would disapprove of the marriage. At the time, it was unseemly to marry a woman without being able to provide for her. Bill and Marjorie secretly married five weeks before his college graduation. They guarded this secret until just before Bill finished law school, three years later. Not even his closest friends knew he and Marjorie were married.

Academically, Bill excelled at Harvard. He scored high enough on his exams to earn a spot in the Legal Aid Bureau, an organization reserved for top students. In June 1931, he finished in the top 10 percent of his class, and officially published his marriage announcement in the Newark Evening News. His mother learned the secret just before then, when Bill planned a botched ceremony to cover up the fact he and Marjorie were already wed. He recalled, “that was a long, long day.”

Career

Bill joined Pitney Hardin, a prominent Newark law firm, as a law clerk. At the time, even as a law school graduate, Bill still had to complete a year-long apprenticeship before he could take the bar exam and officially be a lawyer. Money was tight: He started off making just $75 per month ($1,430 in 2024). When he passed the bar, his salary jumped to $165 ($3,466 in 2024). Though this was enviable to many who were in the thick of the Great Depression, Bill and Marjorie felt pressure to make ends meet until he was made partner in 1938. Bill Senior had died during his second year at Harvard, and the couple was also supporting his mother, Agnes, and the younger siblings.

In 1941, the United States entered World War II and Bill took a leave of absence from the law firm to join the U.S. Army Ordnance Department. Here, he played a crucial role in facilitating the shift to wartime production. The production rate that factories needed to meet put a serious strain on workers, leading to strikes. Following in his father’s footsteps, Bill specialized in resolving disputes between labor and management to prevent worker shortages and work stoppages. The job required Bill to take a significant pay cut and relocate his family twice, but he was eager to serve, especially after two of his brothers enlisted.

After the war ended in 1945, Bill received a warm welcome from Pitney Hardin: The law firm changed its name to Pitney, Hardin, Ward, and Brennan. Bill cultivated a stellar reputation as a lawyer with the Army, and the immediate promotion to name partner when he returned showed how valuable he was to the firm. Labor disputes increased after the war, so Bill’s services were in high demand. The Newark Evening News reported in January 1946 that 1.5 million workers threatened to strike in New Jersey alone. Bill had a long list of clients and successfully provided for his family, though it troubled him to sacrifice time with his two sons when he frequently had to work late into the evening.

Still, Bill found time to dedicate to New Jersey court reform. The state’s court system, with which he had extensive experience as a lawyer, was notoriously inefficient, out-of-date, and corrupt. His reform efforts led the state to create an entirely new court system. When it came time to staff the new courts, the governor offered Bill a judgeship. The position meant a nearly 75 percent pay cut, and Marjorie had just learned she was pregnant with their third child, but he accepted the offer. The opportunity to build the new court system and his passion for reform outweighed the financial sacrifice. He was sworn in as a judge on the New Jersey Superior Court in 1949, then to the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1952.

The Supreme Court

It was on the New Jersey Supreme Court where Bill caught the attention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had a seat to fill on the Supreme Court bench. In addition to his impressive judicial resume, Bill was Catholic. 1956 was an election year, and Eisenhower hoped a Catholic nominee would earn him votes. The Senate confirmed Bill’s appointment to the bench on March 19, 1957. Only one senator dissented: Joseph McCarthy, a Republican representing Wisconsin.

Bill served for 34 terms with the Court under three Chief Justices. He published over 1,250 opinions, including 450 majority opinions and 400 dissents. During Earl Warren’s tenure as Chief Justice, Bill voted with the liberal majority for nearly 98 percent of the time, and even went a full year without writing a dissent. Chief Justice Warren recognized Bill as an ally and made him his “lieutenant.” A charming man, Bill was adept at persuading other justices to sign onto his opinions. He was particularly skilled at accommodating a colleague’s thinking about a case and forging agreements. Chief Justice Warren demonstrated his trust in Bill by assigning him to write the majority opinion in Baker v. Carr (1962), which considered state legislatures’ drawing of electoral boundaries. The Chief Justice later recalled Baker as the most important case he heard on the bench, a testament to how much he valued Bill’s work.

The Chief Justice and his colleagues were also influenced by Bill’s legal philosophy. Bill championed a doctrine called selective incorporation, an approach that individually applied the rights and freedoms outlined in the Bill of Rights to the states. Previously, the Bill of Rights only protected civil liberties from infringements by the federal government. However, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution states that under the law all citizens have due process and equal protection from infringements by state governments. Those Fourteenth Amendment protections, Bill said, should include the most important provisions of the Bill of Rights. In the 1960s, the Court used selective incorporation to recognize and protect the rights of the accused. Landmark cases including Mapp v. Ohio (1961), Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966) all selectively incorporated rights to ensure all citizens are treated fairly in criminal procedures.

Additionally, Bill wrote several notable opinions for the Court that were instrumental in recognizing and protecting individual rights. Fay v. Noia (1963) protected a state prisoner’s right to submit a writ of habeas corpus to federal courts. This allowed the accused to appeal their cases to federal courts, even if the matter had already been resolved on the state level, giving the wrongly accused another avenue of justice. The press won protection from hefty libel suits in New York Times Company v. Sullivan (1964), which also noted that a democracy should have open debate and criticism of government. Here, the Court held that a plaintiff must have proof of “actual malice,” or intentional harm, to sue a publication for false information. In Craig v. Boren (1976), Bill authored the majority opinion that an Oklahoma statute that discriminated between men and women by age in beer sales violated the Fourteenth Amendment. His opinion established the standard for determining when gender bias by the government is unconstitutional. Then, in two cases, Texas v. Johnson (1989) and United States v. Eichman (1990), Bill wrote for the Court that flag desecration was protected speech under the First Amendment.

Eisenhower intentionally chose a Catholic to add representation to the bench, but Bill’s interpretation of the Constitution at times put him in opposition to the principles of the Catholic Church. Moreover, he believed firmly in the separation of church and state. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), Bill voted with the majority to overturn a New York state law requiring public schools to open with prayer. For example, Bill voted to protect women’s privacy to access contraception in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) and the choice to have an abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973).

On the other hand, Bill’s interpretation of the Constitution was consistent with the Catholic Church on the death penalty. Chief Justice Warren thought that Bill’s “belief in the dignity of human beings—all human beings—is unbounded. He also believed that without such dignity men cannot be free.” Bill himself said that all judges should have “a sparkling vision of the supremacy of the human dignity of every individual.” This vision is reflected in the Court’s decision in Goldberg v. Kelly (1970), in which the Court decided that the federal government could not take away a person’s welfare benefits without due process. Bill’s vision of human dignity was extended to his opposition to the death penalty, which he staunchly believed was “cruel and unusual” punishment.

In the 1980s, as Justices from the Warren Court retired and new Justices were appointed, Bill found himself in disagreement more often with his colleagues. In the 1988-89 term, for example, he cast 52 dissenting votes out of 133 decisions—a contrast to his 98 percent majority record in the first 12 years of his service. Still, he was in the majority on several opinions, including a series of cases that established the constitutionality of affirmative action.

Behind Bill’s copious accomplishments on the Court were several personal hardships. The family never adjusted to the salary cut he took when he left private practice and went into debt. Then, in 1969, Marjorie was diagnosed with throat cancer. Bill spent the next 13 years caring for her. Bill reduced his hours at the Court, working late nights at home to care for his family. Later, Bill himself was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1977. He recovered, but then suffered a small stroke. Marjorie died December 1, 1982, and he married Mary Fowler, his long-time secretary, four months later.

Legacy

Under the advice of his doctor, Bill retired at the end of the 1990 term. In retirement, he lectured at various law schools. When he became too ill to teach, he visited the Supreme Court and developed a friendship with his successor, Justice David Souter. In 1993, President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. died on July 24, 1997, at age 91 in Washington, D.C. President Clinton stated that his “devotion to the Bill of Rights inspired millions of Americans” and eulogized him as “the balance wheel who molded the Supreme Court into an instrument of liberty and equality during tumultuous times.” His selective incorporation of the Bill of Rights and landmark decisions on individual civil liberties are now key components of constitutional law.

Discussion Questions

- How did Bill’s upbringing influence his career?

- How did Bill’s Supreme Court decisions protect civil rights and individual liberties?

- Which of Bill’s authored opinions do you believe is the most important? Explain.

- How would you describe Bill’s legacy on the Supreme Court?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Stephen Wermiel for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Cushman, Clare. “William J. Brennan, Jr.: 1956–1990.” The Supreme Court Justices of the United States: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2013.

Ordnance Corps History.” US Army Ordnance Corps. Access April 5, 2024. https://goordnance.army.mil/history/OrdnanceCorpshistory.html

Stern, Seth and Stephen Wermiel. Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion. Lawence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2010.

Featured image: Portrait of William J. Brennan Jr. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.