United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

Significant Case

The landmark Supreme Court decision that affirmed birthright citizenship as a protection under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Background

Towards the late 1800s, a growing number of immigrants came to the United States from Eastern European and Asian countries. Their languages and cultures were noticeably different from what had become mainstream in the United States, and many native-born U.S. citizens perceived their jobs and way of life to be threatened by immigrants who did not assimilate into American culture.

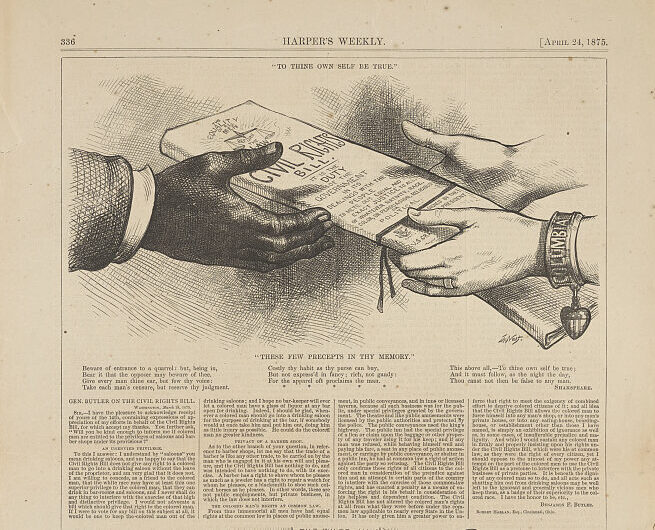

The legal status of these immigrants became a nationwide conversation, especially in light of the Fourteenth Amendment, which had been ratified in 1868. The amendment was created to extend citizenship to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War, but referred to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The Constitution offered little other guidance about who could become a citizen. Congress had passed nationality acts as early as 1790 limiting naturalization to “free white persons” of good character, but in 1870, extended naturalization to all “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent” to include those former slaves who had not been born on U.S. soil.

Additionally, immigrants faced social discrimination, legal injustice, and sometimes violence. Chinese immigrants, on the West Coast especially, became targets of discrimination. In addition to differences in language and culture, Chinese immigrants also looked physically different than other people living in the United States. Nearly 300,000 Chinese laborers entered the country between the end of the Civil War and 1882. While crop failures and famine ravaged parts of China, a growing number of job opportunities in mines and railroads attracted workers to the western United States. Anti-Chinese sentiment quickly grew among nativists, fueled by competition for jobs, xenophobia, and racism. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, mob violence targeted Chinese people living throughout the West Coast.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, effectively banning immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States. Lawmakers strengthened the act several times over the next decade, extending it and adding a requirement that all persons of Chinese ancestry register and carry identification cards at all times. Even carrying proper registration did not guarantee entry into the country. Skeptical customs agents detained hundreds of persons of Chinese descent attempting to reenter the country; they assumed that many were “paper sons” who purchased false documents that claimed their fathers lived in the country as birthright citizens.

Facts

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco, California to Chinese parents in 1873. His parents had lived and worked in the United States for about 15 years and had entered legally. For most of his life, he resided in the same two-block radius of San Francisco’s Chinatown until permanently moving to China in 1931. The family maintained close ties with relatives in China, so Wong (his family name; Kim Ark was his given name) frequently travelled back and forth across the Pacific.

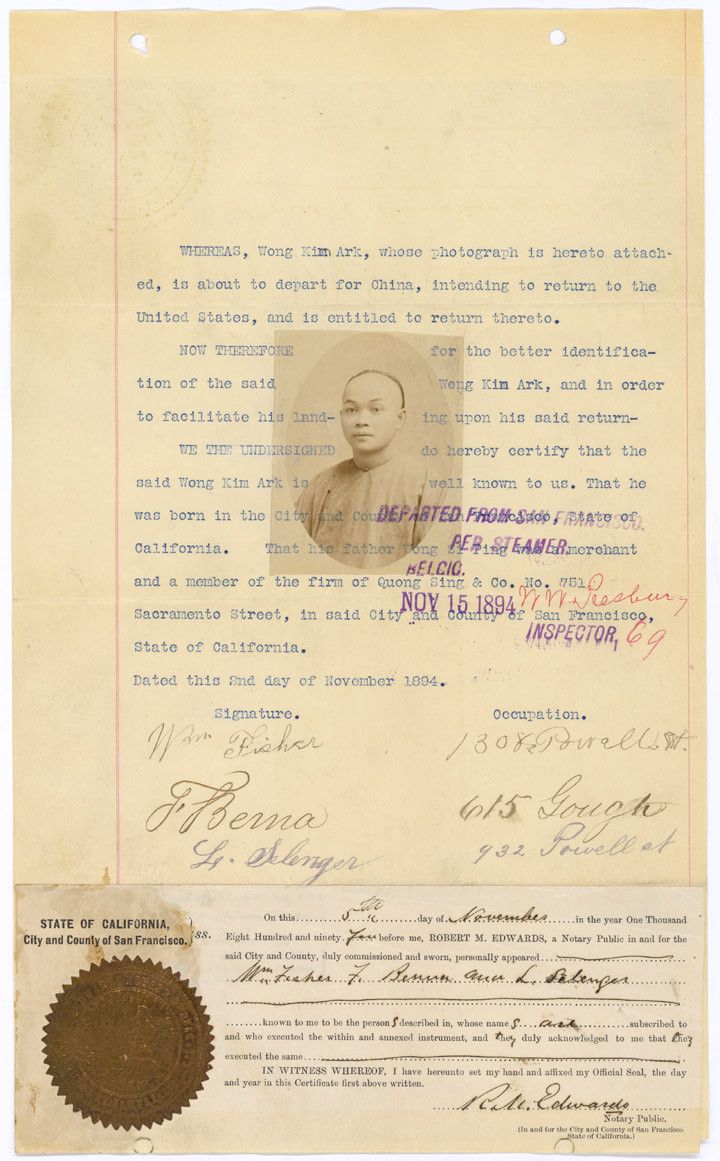

In November 1894, Wong left for an extended visit to China. Before he departed, he ensured that all of his documents were in order. This included a photograph and notarized statements from three white witnesses who could confirm his identity. At the time, travel or identification documents like passports and birth certificates as we know them today did not exist or were extremely uncommon. Due to the Chinese Exclusion Acts, however, all Chinese were required to register and carry identification certificates. There were strict paperwork requirements for re-entry to the states. Despite Wong’s thorough documentation and use of the English language, an immigration officer challenged his citizenship status when he returned to San Francisco in August 1895. Customs officials detained him on steamer ships off the coast, transferring him from ship to ship as they disembarked. He was detained for approximately six months.

The District Attorney for San Francisco, Henry Foote, viewed Wong Kim Ark’s situation as an opportunity for a test case on birthright citizenship. He brought the case In re Wong Kim Ark before the Northern District of California. On January 3, 1896, the court held that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen and ordered him to be released. The government appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Issue

- Who is eligible for birthright citizenship protections under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution?

- Does the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment apply to U.S.-born children of foreign parents?

Summary

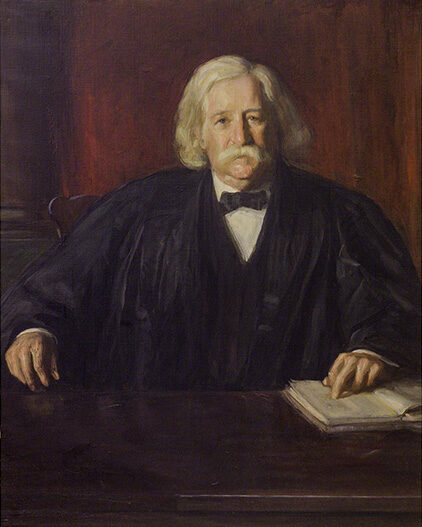

The Supreme Court held in a 6-2 decision that almost all persons born in the United States automatically become citizens. The few exceptions—people not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States—included children of foreign ministers or of invading or occupying military forces, and Native Americans, who owed separate allegiance to their tribal governments at the time. Justice Horace Gray wrote for the majority that over 300 years of English common law practice, often referenced as the foundation of U.S. law, justified the practice of birthright citizenship. Under common law, any foreign person living under English rule was judged to be “within the allegiance, the obedience, the faith or loyalty, the protection, the power, the jurisdiction” of England. Therefore, any child born in England to a foreign national became an English citizen. The majority explained that the United States government had not issued any directive to overturn the idea of birth by citizenship under English Common Law. Justice Gray’s majority opinion cited a number of American court cases in which this principle had been upheld. Justice Gray’s opinion also clarified the Court’s interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The “broad and clear words of the Constitution,” according to Gray, proved that all persons born in the United States were entitled to citizenship, regardless of the Chinese Exclusion Acts. Under its protection, Wong Kim Ark was a United States citizen.

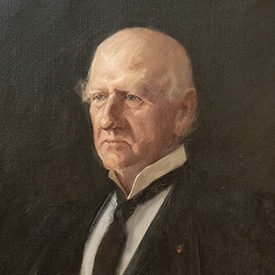

Justice Melville W. Fuller, joined by Justice John Marshall Harlan, dissented. They argued that “the accident of birth” in a particular country was not enough to earn citizenship. Since the United States had now barred the naturalization of Chinese persons, considering them undesirable and unassimilable, their children were no more desirable as citizens than their parents. Justice Joseph McKenna did not take part in the decision, as he joined the Supreme Court after the case had been argued.

Precedent Set

United States v. Wong Kim Ark affirmed birthright citizenship as a protection in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Additional Context

Even after the Supreme Court’s decision bearing his name, Wong Kim Ark could not trust that he could come and go freely between the United States and China. He meticulously filled out the paperwork for his trips to China in 1905, 1913, and 1931 to ensure he would not be stopped by customs officials. An attorney reviewed his forms each time.

Challenges to citizenship continued to arise throughout the 20th century. In 1924, Congress passed the National Origins Act, which created a quota system that placed strict limits on the number of people per country that could immigrate to the U.S. each year. The quotas for Western European countries were significantly higher than Eastern European and African countries. The 1929 annual quota for Great Britain, for example, was 65,721 people. Poland, in contrast, was allowed 6,524 immigrants annually. Egypt was allowed 100. Immigration from Asian countries was almost entirely banned. The quotas remained in place until 1965, when a new immigration act gave all countries a 20,000 annual cap. There was no formal quota on immigration from Mexico, the Caribbean, or Latin America until this new act.

Wars also influenced citizenship in the United States. For example, Mexicans living in territory acquired by the United States after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 became naturalized U.S. citizens and were legally classified as “white.” Despite their legal status as white citizens, Mexican Americans endured de facto segregation and faced several waves of deportation in the 1930s and 1950s. Additionally, the United States won the Spanish-American War in 1898 and acquired the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The three territories received various degrees of citizenship as they came under U.S. colonial rule. Filipinos, after a three-year war for independence, remained under U.S. control until 1942 as “American nationals” without citizenship status. Puerto Ricans received U.S. citizenship status via naturalization in 1917, and birthright citizenship in 1941, and the U.S. extended birthright citizenship to Guam in 1952. During World War II, loyal Japanese American citizens found their status challenged after President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order led to the incarceration of over 120,000 persons of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were United States citizens. The incarceration camps closed after the Supreme Court’s decision in Ex parte Endo (1944).

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

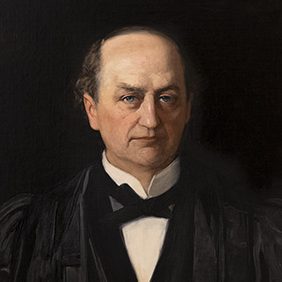

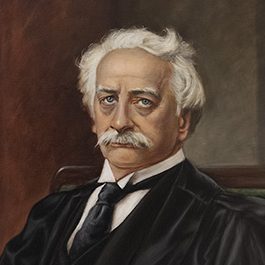

Fuller

-

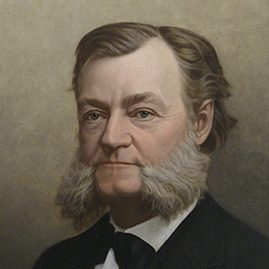

Harlan

-

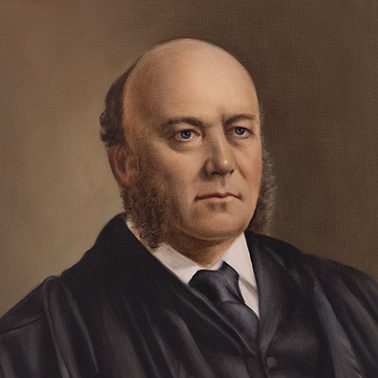

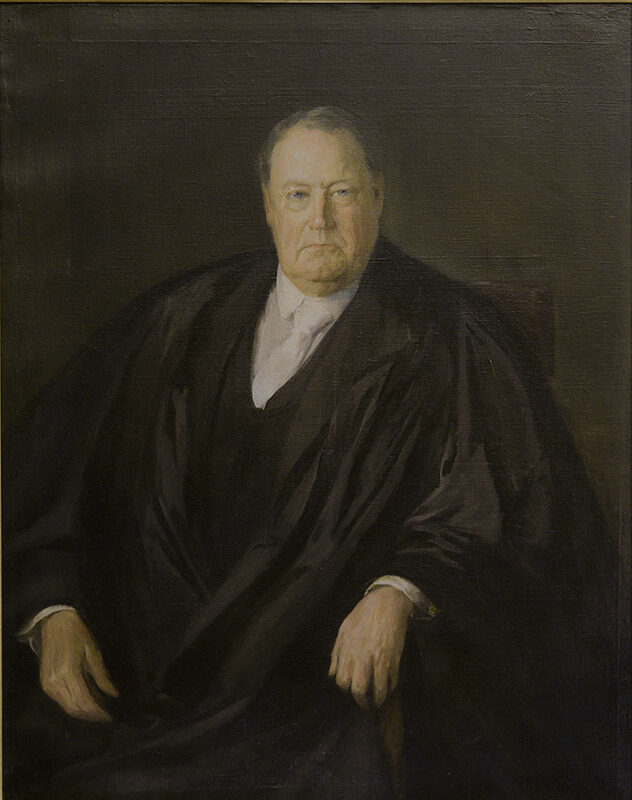

Gray

-

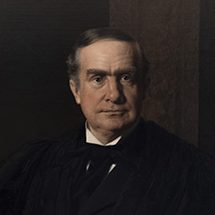

Brewer

-

Brown

-

Shiras Jr.

-

White

-

Peckham

-

McKenna

-

Majority Opinion

Horace GrayRead More CloseThe fact, therefore, that acts of Congress or treaties have not permitted Chinese persons born out of this country to become citizens by naturalization, cannot exclude Chinese persons born in this country from the operation of the broad and clear words of the Constitution, “All persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.”

-

Dissenting Opinion

Melville Weston FullerRead More CloseIt is not to be admitted that the children of persons so situated become citizens by the accident of birth. On the contrary, I am of the opinion that the President and the Senate by treaty, and the Congress by naturalization, have the power, notwithstanding the Fourteenth Amendment, to prescribe that all persons of a particular race, or their children, cannot become citizens…

Discussion Questions

- Why did the legal status of immigrants become a nationwide conversation after 1868?

- How did various groups of people already living in the United States respond to the growing number of immigrants entering the country?

- Why do you think Justice Gray relied on English common law to define citizenship?

- How did United States v. Wong Kim Ark impact the way the Fourteenth Amendment is interpreted?

- Do you think the Court’s decision in Wong Kim Ark resolved the question of who is eligible for citizenship? Why or why not?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and political science professor Carol Nackenoff for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Departure Statement of Wong Kim Ark; 11/5/1894; Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/document/departure-statement-of-wong-kim-ark/, November 13, 2025].

Bernstein, Nina. “Immigration stories, from shadows to spotlight.” The New York Times. September 29, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/30/nyregion/30chinese.html?_r=1.

Diner, Hasia. “Immigration and Migration.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ap-us-history/period-6,

Ely Jr., James W. The Fuller Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacies. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, Inc., 2003.

Nackenoff, Carol and Julie Nokov. American by Birth: Wong Kim Ark and the Battle for American Citizenship. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2022.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).