United States v. E.C. Knight Company (1895)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that limited the federal government’s power to break up monopolies.

Background

During the late nineteenth century, dramatic advancements in technology and transportation led to rapid urban development. New factories, mass production, steam power, and railroads revolutionized the United States’ economy, which shifted from predominantly agrarian to industrial in a matter of decades. To maximize profits, companies across industries—such as steel, oil, railroad, and sugar—consolidated into trusts or holding companies. This business tactic often gave one firm a monopoly and led to a concentration of wealth. With total control over the market, monopolies could, and did, exploit consumers by charging prices above a competitive market level.

The federal government needed to address the extent to which it should regulate these unprecedentedly large corporations. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to prohibit the monopolization of trade. The act outlawed any contract or consolidation that resulted in the “restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations.” There was disagreement, however, on the scope of the act. Questions arose about what regulatory powers belonged to the federal government, and what regulatory powers remained with the states.

Facts

In March 1892, the American Sugar Refining Company (sometimes referred to as the “Sugar Trust”) acquired all four sugar refineries in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: the Franklin Sugar Refinery, the Spreckels Sugar Refinery, the Delaware Sugar House, and the E.C. Knight Company. The acquisitions gave the Sugar Trust control over 98 percent of sugar manufacturing in the United States.

The U.S. Department of Justice sued the Philadelphia companies for illegally monopolizing the industry in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. According to the government, the company should be dissolved because its near-total control of sugar manufacturing illegally interfered with interstate commerce. On the other hand, the Sugar Trust argued that the Sherman Act did not apply to them because the acquired refineries were all in Pennsylvania. Since the manufacture of sugar stayed within state lines, they believed the power to regulate fell to the state of Pennsylvania, not to the federal government.

Both the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Sugar Trust. Control of manufacturing, they held, did not necessarily impact the distribution of sugar across state lines, and remained within the regulatory power of the states. The government appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Issues

- Does the Sherman Antitrust Act violate the Commerce Clause of the Constitution?

- Does the Sherman Antitrust Act apply to monopolization in manufacturing?

Summary

In an 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court affirmed that the acquisitions of sugar refineries were legal under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Manufacturing monopolies, it concluded, did not affect interstate commerce. Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote for the majority that “commerce succeeds to [comes after] manufacturing, and is not a part of it.” Additionally, because the four sugar refineries were in Pennsylvania, the acquisition was not “interstate commerce.” Under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, Congress can regulate business between states, but not within a state. Justice Fuller reasoned that “the fact that an article is manufactured for export to another state does not, of itself, make it an article of interstate commerce.”

In his dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan argued that manufacturing directly affected commerce and as such could be regulated by the federal government. The Sherman Antitrust Act was intended to “protect the freedom of commercial intercourse [trade] among the States against combinations and conspiracies which impose unlawful restraints upon such intercourse.” He asserted that no other “power is competent to protect the people of the United States against such dangers except a national power.” In other words, states could not effectively govern corporations whose business traversed state lines.

Precedent Set

The decision in E.C. Knight narrowed the scope of the Sherman Antitrust Act and limited the federal government’s power to break up large trusts. For the next decade, there were few anti-monopolization cases. Then, in the 1904 Northern Securities case, the Supreme Court affirmed the government’s position and held that the merger of two of the nation’s largest railroads violated the Act, ushering in an era of government “trust-busting.” The following year, the Court’s decision in Swift and Company v. United States found the meatpacking industry’s “beef trust” violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. These decisions did not officially overturn E.C. Knight, but rather reflected different interpretations of the Commerce Clause as the members of the Supreme Court changed over time.

Additional Context

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) became the face of the trust-busting movement. Under his direction, the Department of Justice resumed prosecuting large corporations under the Sherman Antitrust Act. In addition to challenging the trusts, President Roosevelt’s administration oversaw a number of federal regulations that were part of the emerging Progressive movement’s agenda. For example, the Hepburn Act of 1906 strengthened the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroads. Roosevelt and Congress also worked together to create the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Meat Inspection Act to protect consumers.

Trust–busting continued under fellow “progressive” presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson. A 1911 Supreme Court decision broke apart John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, one of the largest corporations in the country. Then, in 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act strengthened the Sherman Antitrust Act. The FTC provided enforcement, while the Clayton Act outlawed certain competition-eliminating practices.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

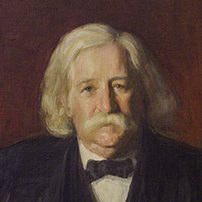

Fuller

-

Field

-

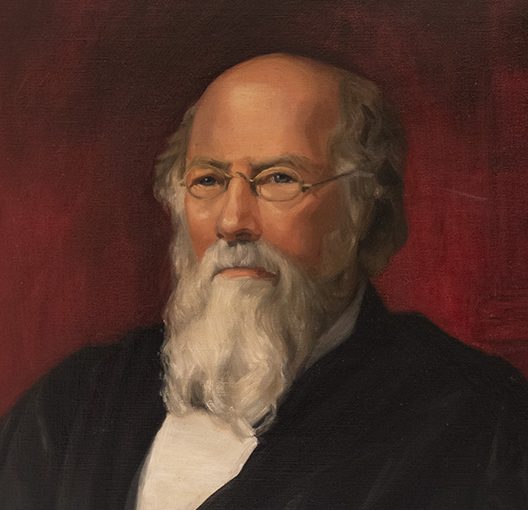

Harlan

-

Gray

-

Brewer

-

Brown

-

Shiras Jr.

-

Jackson

-

White

-

Majority Opinion

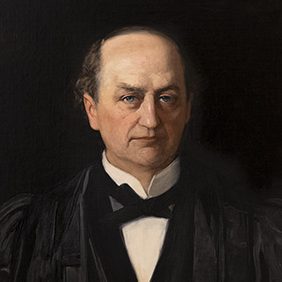

Melville Weston FullerRead More Close“Commerce succeeds to manufacture, and is not a part of it. The power to regulate commerce is the power to prescribe the rule by which commerce shall be governed, and is a power independent of the power to suppress monopoly.”

-

Dissenting Opinion

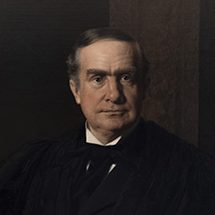

John Marshall HarlanRead More Close“…I perceive no difficulty in the way of the court passing a decree declaring that that combination imposes an unlawful restraint upon trade and commerce among the states, and perpetually enjoining it from further prosecuting any business pursuant to the unlawful agreements under which it was formed, or by which it was created. Such a decree would be within the scope of the bill, and is appropriate to the end which Congress intended to accomplish — namely, to protect the freedom of commercial intercourse among the states against combinations and conspiracies which impose unlawful restraints upon such intercourse.”

Discussion Questions

- Why did businesses choose to create trusts and holding companies?

- How did monopolies impact consumers?

- Why is the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 only constitutional when regulating interstate and international trade and commerce?

- What does this case reveal about federal and state power/rights during this time period?

- How do you think this decision impacted smaller businesses? Explain.

- How did the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Sherman Antitrust Act change over time?

Sources

Special thanks to legal scholar and law professor Laura Phillips-Sawyer for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: The American Sugar Refining Co. buys its raw sugar from planters in Cuba, Java, Philippines, Hawaii, etc. This cargo from Philippines. , 1912. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2022647404/.

“American Sugar Refining Company Records: NYU Special Collections Finding Aids.” American Sugar Refining Company records: NYU Special Collections Finding Aids. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/cbh/arms_2008_042_american_sugar/.

Butler, Allison E. “A Sweet Beginning: The U.S. Sugar Monopoly.” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective. The Ohio State University. January 2019. https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/january-2019-us-sugar-monopoly-E.C.Knight-Sherman-Act-Spreckels-court.

Cherny, Robert W. “Entrepreneurs and Bankers: The Evolution of Corporate Empires.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/ap-us-history/period-6#industrial-capitalism.

Minardi, Lisa. “Sugar and Sugar Refining.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, April 23, 2022. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/sugar-and-sugar-refining/.

“Swift and Company v. United States .” Oyez. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/196us375.

“United States v. EC Knight Co., 156 US 1 – Supreme Court 1895.” Google Scholar, n.d. Accessed May 23, 2025.