Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company (1895)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that declared direct taxes on personal income unconstitutional but was nullified when Congress ratified the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913.

Background

As the Founding Fathers drafted the U.S. Constitution, they intensely debated the idea of federal taxation. Their declaration of independence from the British Crown was significantly motivated by their frustration with the King’s heavy taxes on the colonies to restore his wealth after costly wars. James Madison penned two taxation provisions into the Constitution. While Article I, Section 8 grants Congress the power to “lay and collect taxes,” Section 9 reads, “No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.” In other words, the Constitution prohibited Congress from imposing direct taxes on each person. Instead, it was required to apportion (distribute) taxes based on each state’s population and in proportion to its congressional representation. That way, no state would bear a greater tax burden than others. The question of what constituted a “direct” tax, however, would come before the Supreme Court several times.

Until the Civil War, tariffs and excise taxes composed the primary sources of federal income. The Supreme Court narrowed the definition of direct taxes to flat, per-person taxes and taxes on land holdings in Hylton v. United States (1794) and Springer v. United States (1880). By the late 1800s, the United States was in the midst of rapid industrialization, leading to significant technological advancement. Unfortunately, it also widened the gap between the rich and the poor. New forms of investment, such as stocks and bonds, which mostly the wealthy could afford, could be untaxed sources of revenue. Tariffs and excise taxes no longer generated enough revenue to fund the federal government.

The majority of Americans felt that the permissible taxes disproportionately affected the working class and poor, who were already struggling to make ends meet. A wave of populism, motivated by dissatisfaction with current political parties and economic divide, led to the establishment of the Populist Party, which championed a graduated income tax. When an economic depression gripped the United States in 1893, President Grover Cleveland and the Democrats needed to fulfill their promise to help the American people by reducing tariffs on imported goods. Two Congressmen introduced the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act. The proposed legislation would reduce tariffs and impose a 2 percent income tax on all income over $4,000 ($103,000 in modern dollars). If passed, this legislation would allow President Cleveland to raise the needed revenue the government lost by reducing tariffs without placing the burden on working-class Americans.

Gilded Age businessmen adamantly opposed the tax because it would cut into their profits and they resisted “opening the door” to more direct taxes. They branded the act as class legislation and a violation of personal rights. Many industrialists followed Andrew Carnegie’s essay “Gospel of Wealth” and voluntarily used some of their wealth to build libraries, schools, and national parks open to every American. They believed they could best determine how to help the less fortunate through charity work rather than have the government redistribute their money through taxes. Progressives, however, viewed the income tax as a more equitable way to fund the government and force the wealthy to pay a greater share of the nation’s budget. Numerous Senators, however, sought to avoid some of the bill’s impact on specific industries and made changes that weakened it. On August 27, 1894, Congress passed the modified version of the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act.. The controversial act created a legal question and quickly generated a test case: did the Constitution’s prohibition on direct taxes cover this new tax, too?

Facts

Lawyer William Dameron Guthrie believed the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act violated the Constitution and decided to challenge it in federal court. To secure a victory, however, Guthrie also had to convince the Justices that several Supreme Court precedents defining “direct tax” were incorrect. He also had to persuade the Court to hear the case before the act took effect, overcoming its prohibition on “advisory opinions.”

Guthrie set a plan in motion. He encouraged Charles Pollock, who owned ten shares in Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company, to sue the bank to prevent it from paying the new tax, which would reduce his investment profits. Viewing this as a live dispute, the Supreme Court quickly scheduled oral argument for March 7, 1895.

Issues

Is the income tax included in the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act essentially a “direct tax” in violation of the Constitution?

Summary

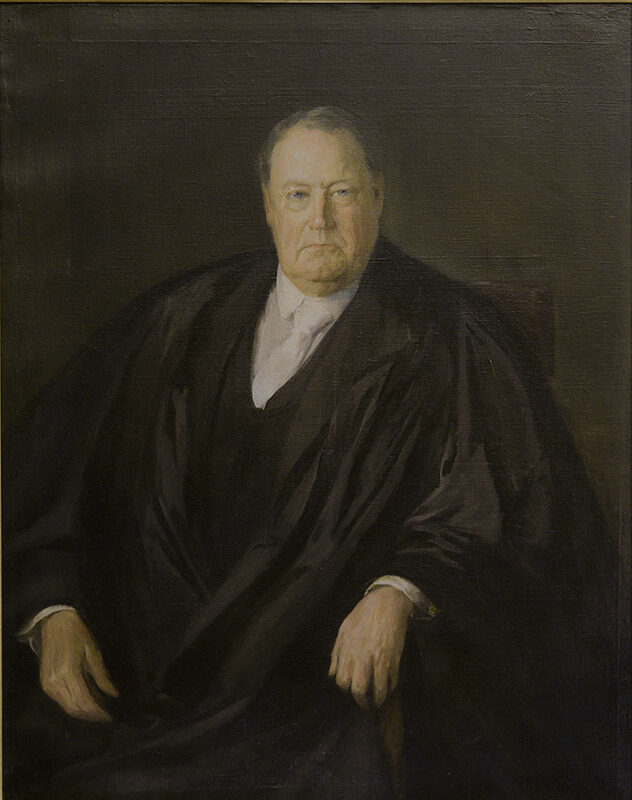

The Supreme Court heard the Pollock case twice. During the first hearing, Justice Howell E. Jackson remained at home due to illness, and an eight-member bench heard the case. Chief Justice Melville Fuller issued the Court’s opinion that was tied 4-4 on the central issue of whether an income tax was a direct tax.

Unsatisfied with the results, Pollock asked for a rehearing. The Court granted it, and Justice Jackson, while terminally ill, managed to participate. During the second deliberation, Chief Justice Fuller considered the Hylton and Springer precedents, but he dismissed them as being distinguishable from the case before the Court. In May of 1895, Fuller handed down the nine-member Court’s 5-4 decision in favor of Pollock. The majority held that “taxes on personal property, or on the income of personal property, are likewise direct taxes.” The Court held that the entire act should be struck down because it was a direct tax that had to be apportioned among the states according to their populations under the Constitution.

Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented, joined by Justices Jackson, Edward White, and Henry B. Brown. During the Pollock decision’s announcement in the Court, he forcefully delivered the dissent out loud, declaring, “It strikes at the very foundations of national authority, in that it denies to the general government a power which is or may become vital to the very existence and preservation of the union…” Now that wealthier individuals and corporations could not be taxed, he emphasized the increasing disparity between the rich and poor, stating, “in large cities…there are persons deriving enormous incomes from renting houses…possessing vast quantities of personal property, including bonds and stocks…In the same neighborhoods” working-class Americans “whose income arises from [their] skill” would continue to bear the burden of taxation through tariffs and other levies “directly from their earnings.” Justice Brown added that the majority decision “involves nothing less than the surrender of the taxing power to the moneyed class.”

Precedent Set

Though the Supreme Court did not rule that all income taxes were direct taxes, it held that taxes on interest, stock dividends, and real estate income were direct. By striking down these types of taxes, wealthier individuals and corporations were exempt from increases to their tax burdens. For the rich, the Gilded Age era continued for two more decades. Congress did not attempt to create a federal income tax again until 1909.

Additional Context

The decision in this case ultimately led to an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In 1909, Nebraskan Senator Norris Brown and Rhode Island Senator Nelson W. Aldrich led the proposal of the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which reads:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

Many initially felt the amendment would not pass, but a group of Democrats and progressive Republicans worked diligently to ensure that both houses of Congress enacted it. In the four years that followed, rising living costs and the prospect of a steadier source of federal revenue persuaded many to support the new amendment. February 25, 1913, marked a historic occasion—the required three-fourths of the states ratified the amendment, the first constitutional amendment in almost fifty years. The Sixteenth Amendment replaced the Supreme Court’s 18-year-old Pollock decision as the new law of the land. Shortly after, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1913. The highest income tax rate in the act was seven percent, while the lowest was one percent. This act accomplished President Cleveland’s goals from two decades prior: lower tariffs and the implementation of a federal income tax. By 1945, however, the industrialists’ fears came to fruition. The highest federal income tax bracket rose to 94 percent and remained above 90 percent until 1963.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

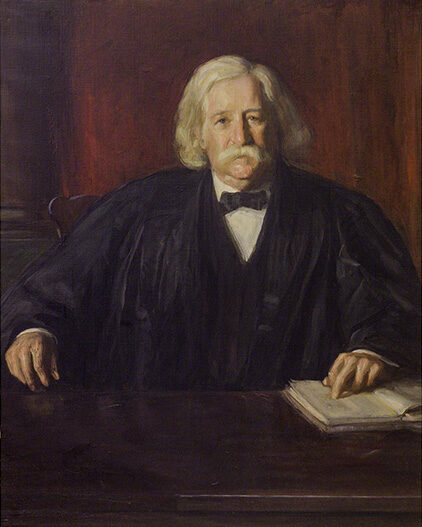

Fuller

-

Field

-

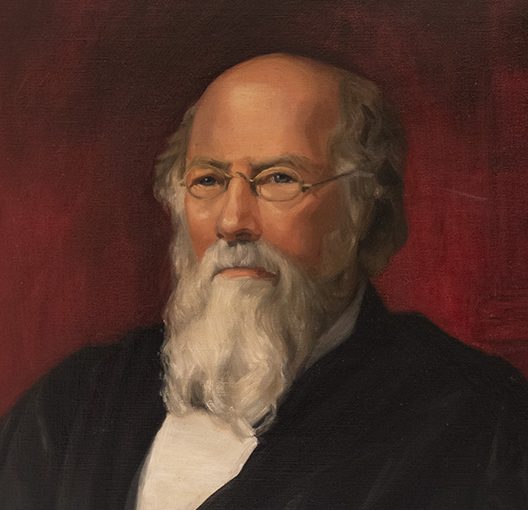

Harlan

-

Gray

-

Brewer

-

Brown

-

Shiras Jr.

-

Jackson

-

White

-

Majority Opinion

Melville Weston FullerRead More Close“Taxes on personal property, or on the income of personal property, are likewise direct taxes.”

-

Dissenting Opinion

John Marshall HarlanRead More Close“It strikes at the very foundations of national authority, in that it denies to the general government a power which is or may become vital to the very existence and preservation of the union…”

Discussion Questions

- Why did the Progressives support the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act?

- Why were the Gilded Age businessmen and wealthy Americans opposed to the income tax?

- What was the Supreme Court’s reasoning for striking down the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act?

- Using Justice Harlan’s and Justice Brown’s dissents, compare and contrast the effects of the Pollock decision on different groups of American people.

- How does the outcome of Pollock v. Farmers’ Loans and Trust Co.and the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment illustrate the principle of checks and balances?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar Peter S. Canellos for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: “The Last Unfortunate Experience of an Unfortunate Animal.” Puck. Illustration. May 1, 1895. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012648625/

Bradford Tax Institute. (2025) History of Federal Income Tax Rates: 1913-2025. Bradford Tax Institute. https://bradfordtaxinstitute.com/Free_Resources/Federal-Income-Tax-Rates.aspx

Canellos, Peter S. The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021.

Ely, James W., Jr. “Melville W. Fuller Reconsidered.” Journal of Supreme Court History, 23-1: 35-49 (1998).

Hylton v. United States, 3 U.S. 171 (1796)

Johnson, Calvin H., “The Four Good Dissenters in Pollock.” Journal of Supreme Court History, 32-2: 162-177 (20074).

Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895)

Rooks, Douglas. Calm Command: U.S. Chief Justice Melville Fuller in His Times, 1888-1910. Thomaston, ME: Maine Authors Publishing, 2023.Springer v. United States, 102 U.S. 586 (1880)