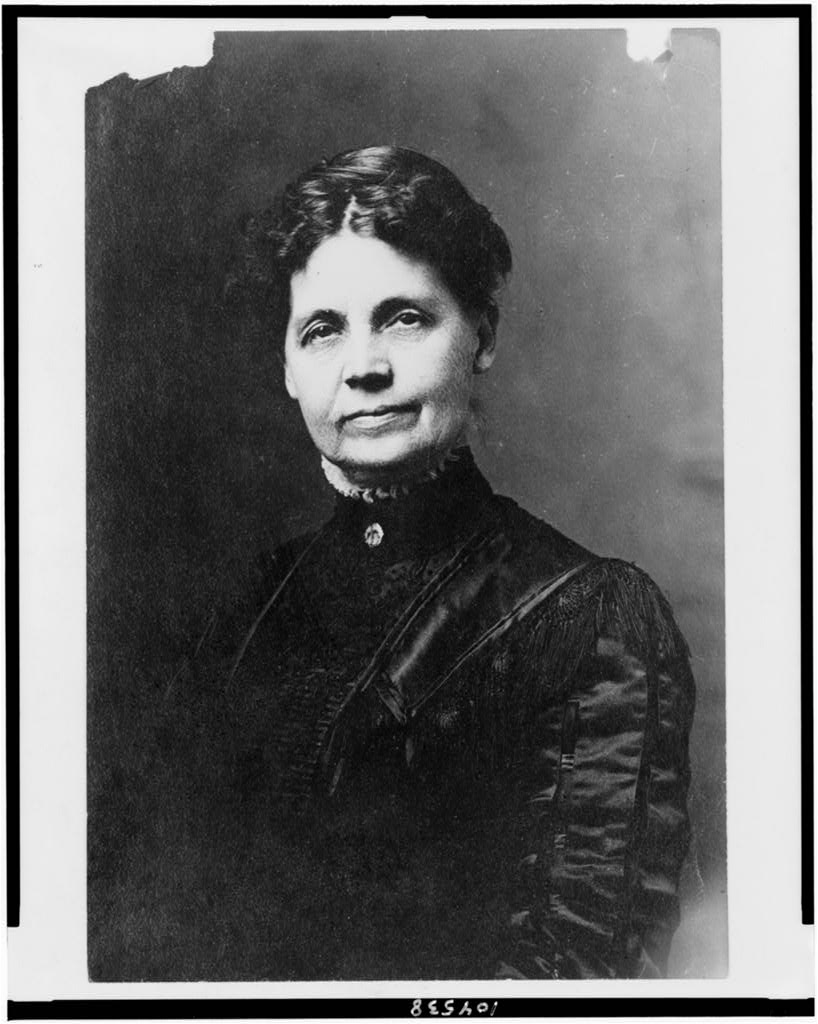

Malvina Shanklin Harlan

Life Story: 1839-1916

The daughter of Northern abolitionists who became the influential wife of an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

Background

Malvina “Mallie” French Shanklin was born in southern Indiana in 1839, in the midst of pre-Civil War sectionalism. The second of four children, she was the only daughter of John and Philura Shanklin. Originally from New England, her parents were staunch abolitionists and much of her extended family was anti-slavery. Mallie’s father, a wealthy merchant, provided a relatively comfortable childhood. As a school teacher, her mother instilled life lessons often guided by her Presbyterian faith. In addition to the guidance she received from her mother, particularly in the area of housewifery, Mallie attended both the Glendale Female Seminary near Cincinnati, Ohio and the Presbyterian seminary Misses Gill’s School. These private schools offered coursework similar to four-year colleges and made education more accessible to women. During her time at Glendale, Mallie lived with an uncle who adored her. He made sure she had beautiful dresses and sent her to dances every Monday night. Mallie was also an accomplished musician, especially on the piano. Her uncle purchased her an $800 piano to practice and ensured she experienced a happy childhood.

Mallie first saw her husband, the future Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, when she was only 15 years old. For Mallie, it was love at first sight. She recalled in her memoir that she could “still see him as he looked that day—his magnificent figure, his head erect, his broad shoulders well thrown back—walking as if the whole world belonged to him.” She saw him again a few months later at a neighbor’s dinner party, enthralled by the way he “played horsey” with the host’s young nephew. The two spent the rest of the evening talking—and she was so infatuated that her mother told her, “you have talked quite enough about a young man whom you have only seen for an hour or two.” John was equally enamored. The 21-year-old lawyer called on her every day for two weeks and asked her to marry him. While the Shanklins thought highly of John, they believed Mallie was too young to marry and insisted on a two-year engagement. Mallie and John married at her parent’s home on December 23, 1856.

Marriage to John Marshall Harlan and Life in Kentucky

Mallie and John moved to his family home in Frankfort, Kentucky, where they lived with his parents along with his siblings and their families. Eventually, the couple had six children of their own—three boys and three girls. For many years, Mallie continued the musical hobbies she took pride in during her youth. She proudly served as the choir organist for their church in Frankfort. A “music club” eventually formed and Mallie reveled in the growing musical interest their group sparked in the town. John supported Mallie’s activities and “was always ready to stay at home with the little ones,” so that she could attend her rehearsals. Additionally, he encouraged her to attend professional music performances, even when he could not accompany her. Mallie happily passed down her love of music to her own children.

Moving in with her in-laws presented Mallie with a culture-shock. Unlike her family, the Harlans owned several slaves. The experience challenged Mallie’s views on slavery as she reconciled her abolitionist upbringing with the reality she lived in the Harlan house. Most of the enslaved people there did housework and gardening, as opposed to the grueling labor and brutal violence she knew occurred on large plantations.

The Civil War

When the Civil War broke out, Kentucky remained in the Union as a border state. Despite being anti-secession, John struggled with his decision to join the army because he was concerned about leaving his growing family. Mallie remembered telling him that she would “not stand between [him] and [his] duty to the country.” Ultimately, he decided to enlist. The couple exchanged daily letters during his two years in the Army.

During the war, Mallie and her children moved back to Indiana, away from the fighting in the South. Like John, her older brother, James Maynard Shanklin, served as an officer and recruiter for the Union Army. Captured by Confederate forces in late 1862 and imprisoned in Richmond, Virginia, James died only days after returning home in May 1863.

John also suffered significant loss during the war when his father suddenly passed away in February 1863. John resigned from military service and the Harlans returned to Frankfort, where John took over the family law practice and was elected attorney general of Kentucky. After the war ended in 1865, the family moved to Louisville where John unsuccessfully campaigned for governor in 1871 and 1875. By this time, John identified politically as a Republican after leaving the Whig Party, and had come to denounce slavery and racial discrimination.

Life as a Supreme Court Wife

John’s reputation as a lawyer and two runs for governor brought him national recognition. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed John to the Supreme Court and the Harlans moved from Kentucky to Washington, D.C. The cross-country move to an unfamiliar place led the Harlans to take a suite of rooms in a boarding house. Mallie reflected that this decision allowed her “to take a rest from housekeeping,” and become more familiar with her new role. She was “filled with some apprehension [that] the quiet life of a judge might be irksome and monotonous and [she] endeavored in every way to make the change a desirable one.” As a Justice’s wife, Mallie hosted regular at-home receptions on Monday afternoons that were often attended by 200 to 300 people. This hosting responsibility was expected of the wives of Supreme Court Justices during this time period and was expensive and burdensome. The parties allowed Mallie to form and keep relationships with important members of Washington D.C.’s political circles, which benefited her husband while he served on the Court. Mallie and her oldest daughter, Edith, entertained visitors weekly with music, dancing, and large table spreads.

Mallie also developed a close friendship with First Lady Lucy Hayes. As a result, the Harlans frequently attended dinners and other events at the White House. Mallie remembered one such dinner where the wives of the Justices teased Chief Justice Morrison Waite for having denied Belva Lockwood’s application to be admitted to practice law before the Supreme Court. After working for six years to get male-supported legislation passed that allowed qualified women to be admitted, Lockwood became the first woman admitted to the Supreme Court Bar in 1879.

Two years later, in 1881, the Harlans moved from their boarding house to a home on Massachusetts Avenue where the whole family lived together. Having the entire family together delighted Mallie and she was particularly grateful for her daughter Edith’s presence. Described as “the life of our household,” Edith not only assisted Mallie with hosting duties, but also graciously helped look after her younger siblings. The same year the Harlans moved to their new home, Edith married Linus Child in a joyful ceremony that included the entire family. Within 13 months Edith died of typhoid fever shortly after giving birth to a daughter who Mallie and John helped raise as their own. Following Edith’s death, the family struggled to go back to their Massachusetts Avenue home that held so many memories. The Harlans moved to Rockville, Maryland, outside of Washington, D.C. for two years, before permanently settling in the University Hill neighborhood in Washington. Both Mallie and John cherished their time in this home, with Mallie remembering John fondly looking up each time they returned from travels and saying, “Oh, it is good to be home again.”

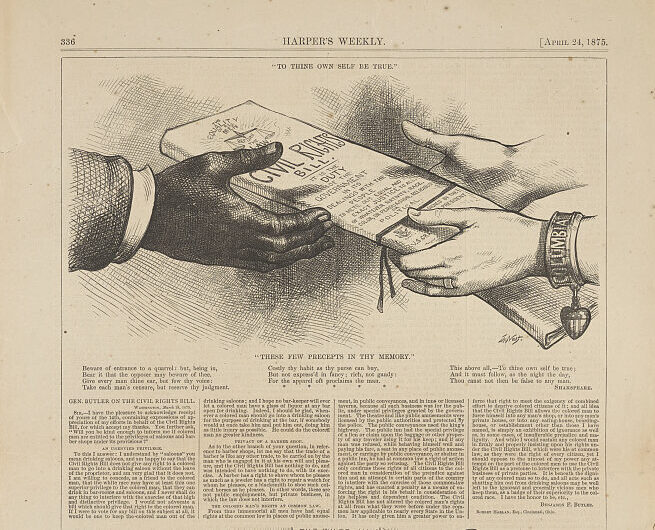

Mallie’s ultimate duty as the wife of a Supreme Court Justice was to support her husband as he deliberated on momentous decisions and he often looked to her for advice. She took great pride in his nickname for her: “Old Woman,” as she felt it illustrated his belief and confidence in her experiences and judgement. She proved particularly influential as he completed his dissent in the Civil Rights Cases (1883). John Marshall Harlan, an avid collector of historical artifacts, owned the inkstand that Chief Justice Roger Taney had used to write the infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857. In that landmark case, the Court held that African Americans were not, and could not become, citizens of the United States. He planned to give the inkstand to one of the late Chief Justice’s relatives, but Mallie, thinking that it would be valuable to John one day, hid it away. When John struggled with his dissent in 1883, Mallie pulled out the inkstand, cleaned it off, and set it up at his writing desk. It gave him the inspiration he needed to quickly write his dissent, in which he argued that the Fourteenth Amendment intended to protect all citizens from discrimination. Mallie remembered, “the memory of the historic part the inkstand had played…in temporarily tightening the shackles of slavery…seemed, that morning, to act like magic in clarifying my husband’s thoughts…His pen fairly flew on that day and he soon finished his dissent.”

Legacy

John and Mallie celebrated 50 years of marriage in December 1906. They planned a large reception to mark the occasion, with John insisting that they “must make it a day long to be remembered by [their] children and grand-children.” John even took the time to describe Mallie’s wedding bouquet to their daughter-in-law so that a matching “golden” bouquet could be made for Mallie to carry during their celebration. When asked about it, Mallie joyfully told admirers that “an old sweetheart ordered it,” while looking adoringly at her husband. After being married for almost 55 years, Mallie honored John’s role as a husband and father after his death in 1911. While John wished to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery in honor of his military service, Mallie defied his request and purchased a plot in Rock Creek Cemetery where there would be enough room for the couple and all of their children. She also wrote a memoir of their life together, Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854-1911.

Though much of her life revolved around her family, Mallie embraced her independence. In 1892 after a family tour of Europe, she “took [her] courage in both hands” and extended her trip after the rest of her family returned home. Later, in 1908, she represented Kentucky at a Child’s Welfare Conference in Washington, D.C, an appearance requested by the Governor of Kentucky. Though she happily conformed to the strict gender roles of the time period, Mallie’s moments of independence prove she had more in common with the emerging bold and modern woman than she gave herself credit for.

Mallie died in 1916 as a result of an accident that left her with a broken hip. Remembered as a popular and courageous woman, Mallie’s legacy on the Court continued long after she died. Her grandson, John Marshall Harlan II, became a Supreme Court Justice in 1955, serving for 16 years until 1971.

Discussion Questions

- Explain how Mallie’s upbringing influenced her perspective on slavery and how her views changed over time.

- What was Mallie’s main priority during her adult life?

- Why do you think Mallie defied her husband’s wish to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery? What does this tell you about how she viewed ultimate accomplishments in life?

- Although she was not in a position of political power, how did Mallie wield influence on topics that were important to her?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and history professor Linda Przybyszewski for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Mrs. Malvina F. Shanklin Harlan, half-length portrait, facing front. , None. [Between 1870 and 1900?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92501258/.

Beth, Loren P. John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice. The University Press of Kentucky, 1992.

Ginsburg, Ruth B, Remarks of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, March 11, 2004, CUNY School of Law, 7 N.Y. City L. Rev. 221 (2004)

Harlan, Malvina Shanklin, and Linda Przybyszewski. Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854-1911. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

Latham, Frank. The Great Dissenter Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan. Cowles Book Company, Inc., 1970.

Przybyszewski, Linda. “Introduction.” Journal of Supreme Court History 26, no. 2 (2001): 106. https://doi.org/10.1353/sch.2001.0009.

Przybyszewski, Linda C. A.. “Mrs. John Marshall Harlan’s Memories: Hierarchies of Gender and Race in the Household and the Polity.” Law & Social Inquiry 18, no. 3 (1993): 453–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/828470.

Przybyszewski, Linda. The Republic According to John Marshall Harlan. University of North Carolina Press, 1999.