Loving v. Virginia (1967)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that upheld equal protection and due process in regard to interracial marriage.

Background

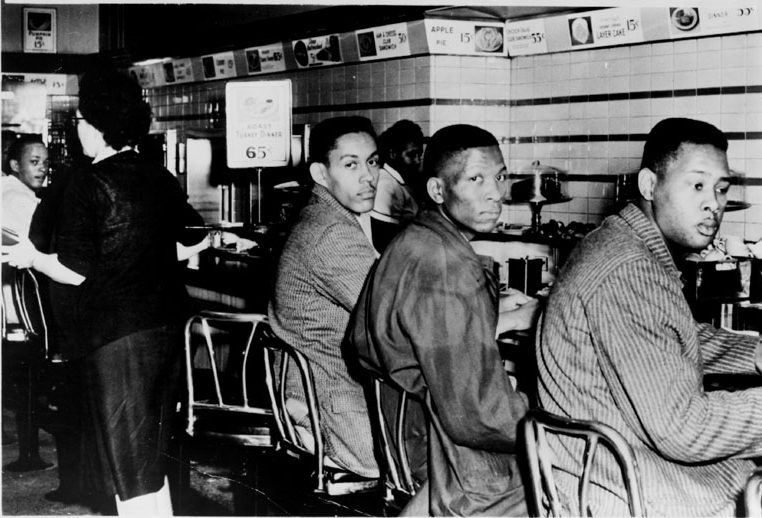

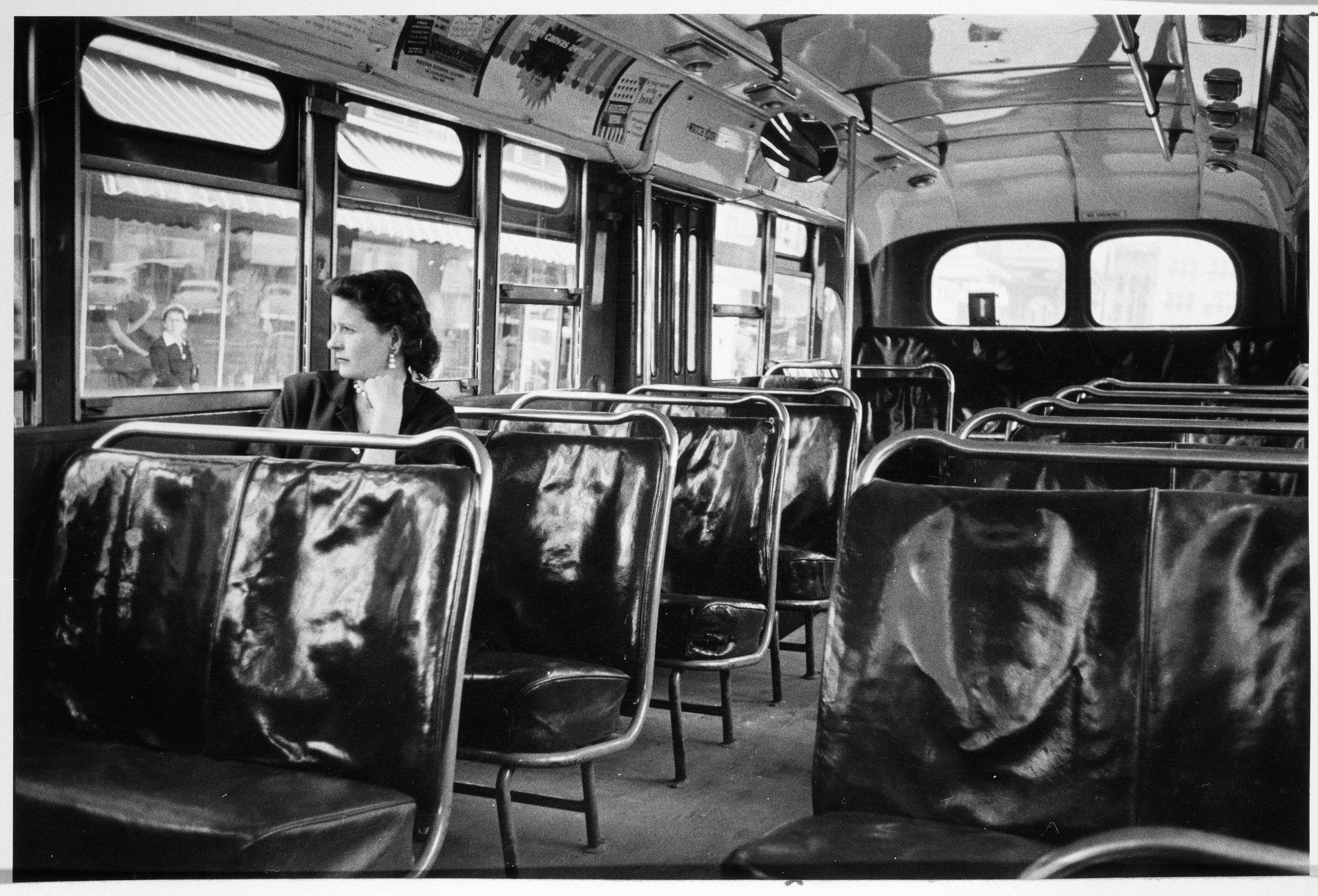

At the end of the Reconstruction era, many Southern states enacted legislation aimed at circumventing the rights and legal protections that the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to provide for newly freed Black people. These Jim Crow laws regulated all facets of life, including the right to marry.

Anti-miscegenation laws were established throughout the course of U.S. history to criminalize interracial dating and marriage. Some of these laws, such as those in Virginia and Maryland, predated the creation of the United States, while more were established after Reconstruction. All but nine states (Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington, D.C.) enacted laws forbidding interracial marriage. An interracial couple, Tony Pace and Mary J. Cox, challenged one such law in Alabama after they were convicted of living together and sentenced to two years in prison. The Supreme Court affirmed the state’s judgment in Pace v. Alabama (1883), holding that the law was constitutional because both parties were given the same punishment. After Pace, courts consistently struck down cases challenging anti-miscegenation laws.

By the 1950s and 1960s, however, the Supreme Court issued several opinions that recognized and protected individual rights, began reviewing cases about anti-miscegenation laws. In McLaughlin v. Florida (1964), Dewey McLaughlin, a Black man, and Connie Hoffman, a white woman, were charged with violating Florida’s anti-miscegenation law by cohabiting as an unmarried couple. They appealed their case to the Supreme Court, which found that part of the state law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. At this point, the Pace ruling was overturned, but the Court did not address the portion of the law pertaining to interracial marriage. After the decision in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) recognized the right to privacy in a marriage, the Supreme Court appeared more willing to address state laws banning interracial marriage.

Facts

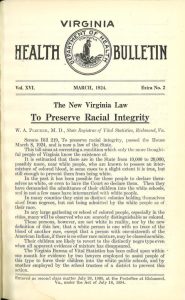

Virginia was one of 29 states with anti-miscegenation laws in 1924 when it passed the Racial Integrity Act, a law influenced by the eugenics movement. The act updated state anti-miscegenation laws that had been on record since 1691. It defined Virginians by strict racial categories of “white” and “colored” and the legislature banned marriages between people in different races.

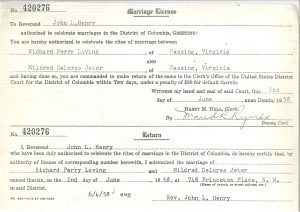

Rural communities in Virginia were often multiracial, consisting of residents of white, Black, and Native-American heritage, all living and working together. One such community, Central Point, located between Washington D.C. and Richmond, was home to Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter. Richard, a white man, and Mildred, a Black and Native-American woman, intended to live their lives together and raise their family in their hometown. However, their marriage was illegal under the Racial Integrity Act. The high school sweethearts married June 2, 1958 in Washington D.C. to avoid breaking the law. Nine days later, police raided their Central Point home and charged them with illegally cohabitating. The Lovings pleaded guilty and were sentenced to one year in jail. The judge agreed to suspend their sentence for 25 years if the couple moved out of Virginia.

For four years, Richard and Mildred lived in Washington D.C., missing their extended family and home in Virginia. After a car accident injured one of their four children, they moved back to Central Point and were quickly arrested. Both Richard and Mildred were prosecuted under the 1924 Racial Integrity Act and charged with the same crime.

The Civil Rights Movement was gaining support from Americans across the nation. Additionally, President John F. Kennedy’s administration supported equal rights. Mildred wrote a letter to Attorney General Robert Kennedy to ask what action could be done to help her and Richard return to their home in Virginia. While he could not help, he directed Mrs. Loving to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) for assistance.

Two young lawyers from the ACLU, Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, took the case and asked a state trial court to vacate the Lovings’ conviction in 1963. The lawyers argued that the Lovings’ rights were violated in accordance with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The judge delayed addressing the appeal, so Cohen and Hirschkop filed a motion in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The parallel filing pressured the state court to hear the appeal. In January 1965, the judge who originally heard the Lovings’ case six years prior denied the request to vacate citing that “marriage was a subject which belongs to the exclusive control of the States.” The Lovings appealed their case to the Virginia Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court’s ruling.

The Lovings petitioned the Supreme Court of the United States. On December 12, 1966, the Court agreed to hear their case.

Issue

Do state laws prohibiting interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Summary

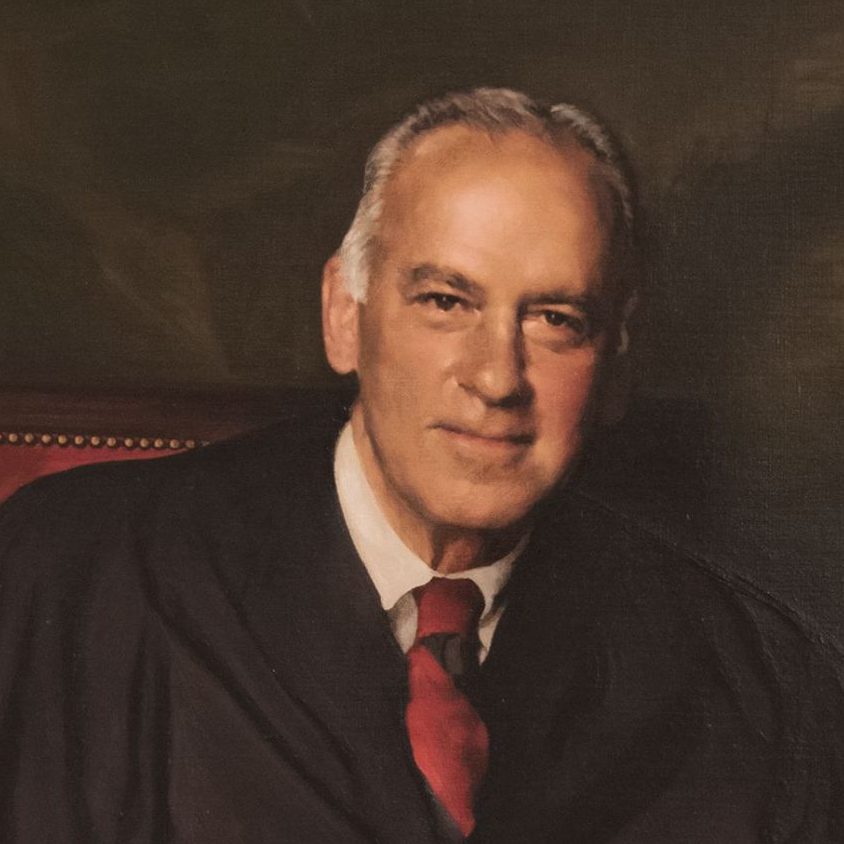

In a unanimous decision issued on June 12, 1967, the Court ruled in favor of the Lovings. In his opinion Chief Justice Earl Warren did not agree with Virginia’s argument that equal penalties for the spouses made the law non-discriminatory. He wrote that “the freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men,” and that the law also violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because it was not illegal for other non-white couples to get married, the Court concluded that the intent of the Virginia law was to uphold white supremacy.

Precedent set

After Loving v. Virginia, remnants of federal and state segregation laws were overturned. The decision impacted the remaining 15 states with anti-miscegenation laws and recognized marriage as a protected fundamental right included in the Fourteenth Amendment. County clerks around the country could no longer use race to deny a couple a marriage certificate.

The Loving Court’s decision on interracial marriage had far-reaching implications, also protecting spouses in interracial marriages from the denial of inheritances, alimony, and death benefits based on race.” Additionally, under Loving, a child could no longer be taken away from a parent who remarries a partner from a different race. According to a 2015 Pew Research study, 17 percent of all U.S. newlyweds had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity.

The Court referenced the Loving v. Virginia case in subsequent opinions pertaining to marriage, most notably in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which held that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples.

Additional Context

Supporters of legalizing interracial marriage saw a path forward after Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared school segregation unconstitutional. School segregation laws actually doubled as anti-miscegenation laws: if students went to school together, segregationists feared, interracial marriage would occur, threatening racial purity and white supremacy. By the end of the 1950s, eight states overturned their anti-miscegenation laws.

During the Civil Rights Movement, religious leaders around the country supported striking down the marriage laws. In their eyes, the right to decide who to love was as important an individual choice as the right to decide which religion to practice and support.

Some local jurisdictions throughout the South refused to comply with the Court’s decision in Loving. They refused to issue marriage certificates or would implement outdated state laws. At times in the late 1960s and 1970s, federal courts had to step in to ensure the rights of interracial couples were not infringed.

Decision

The Court issued a unanimous decision for Loving.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

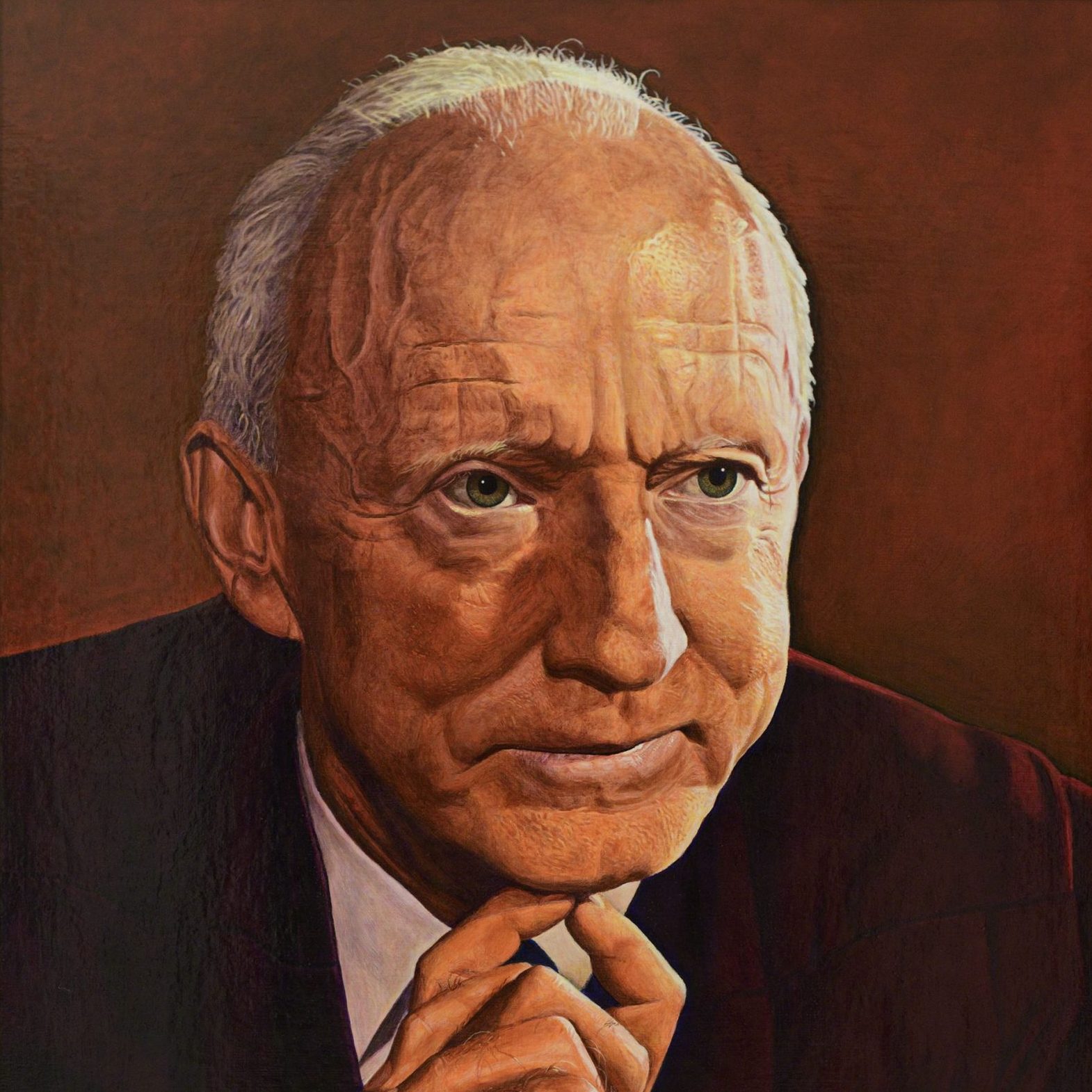

Warren

-

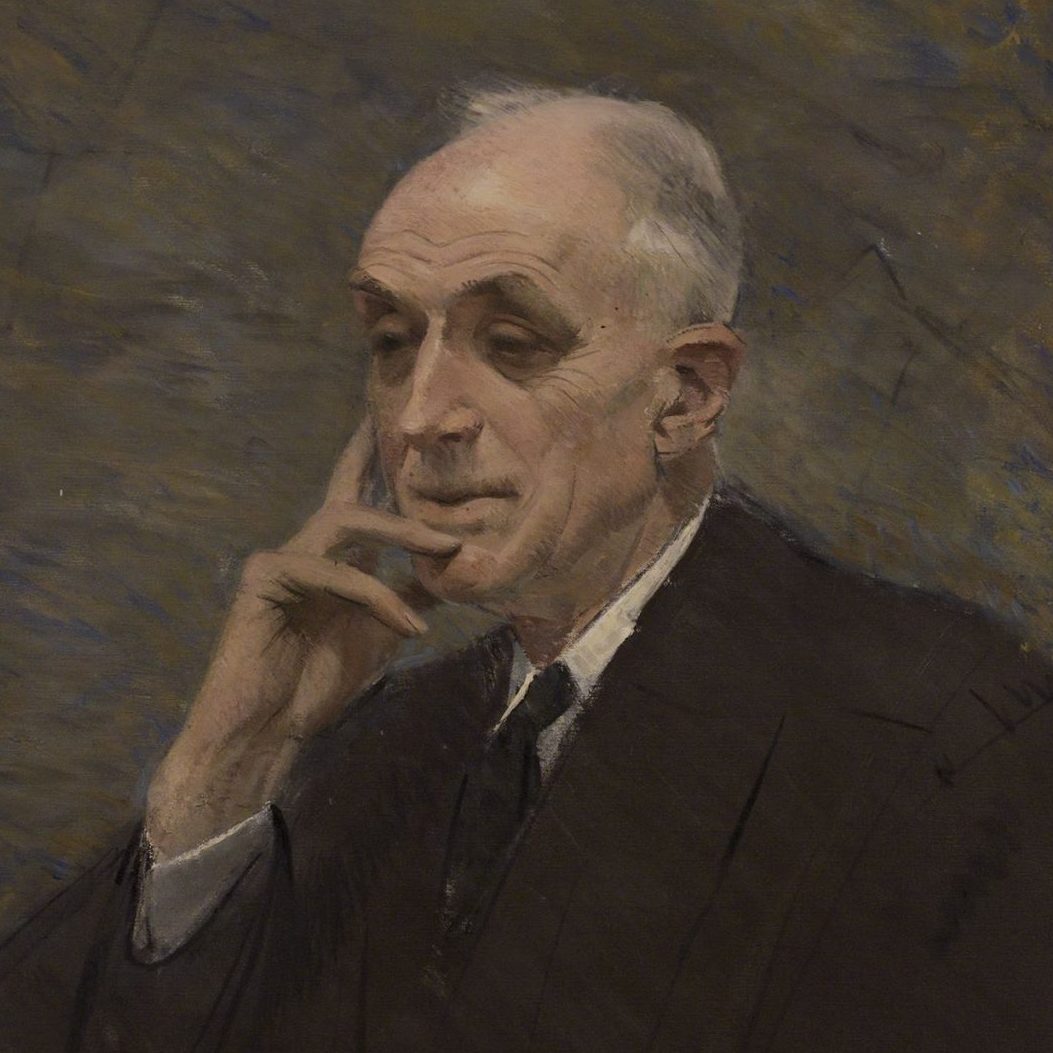

Black

-

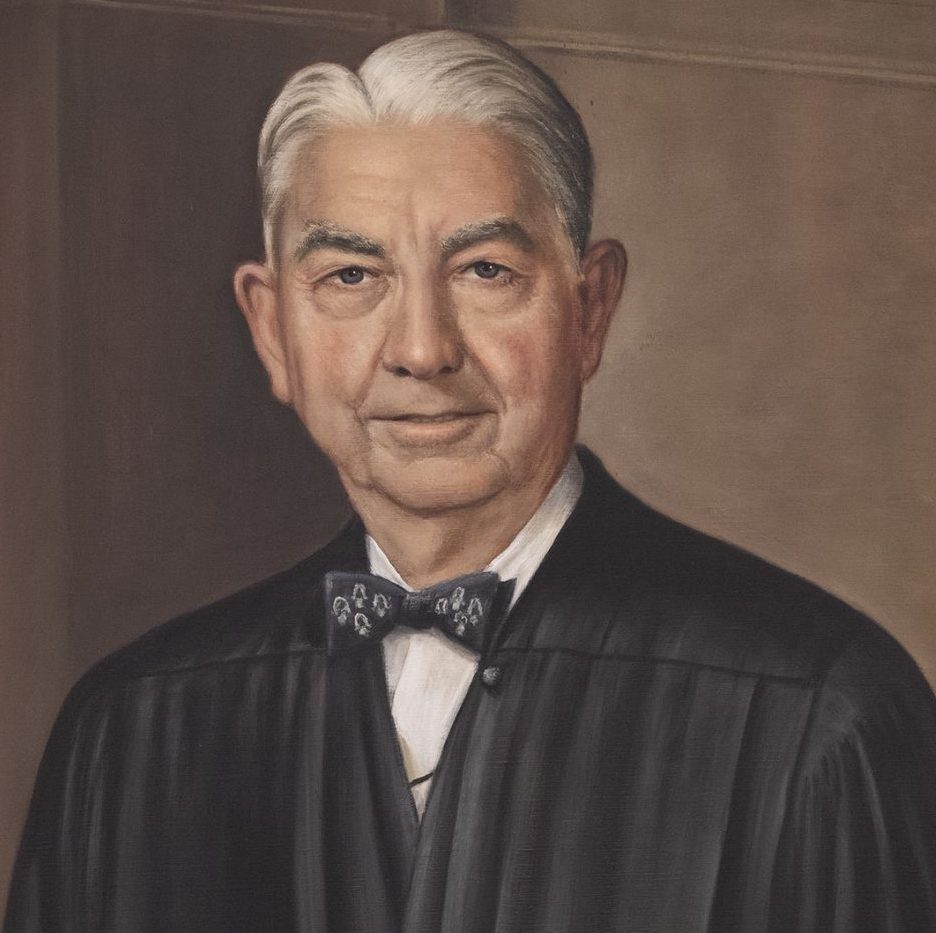

Douglas

-

Harlan II

-

Clark

-

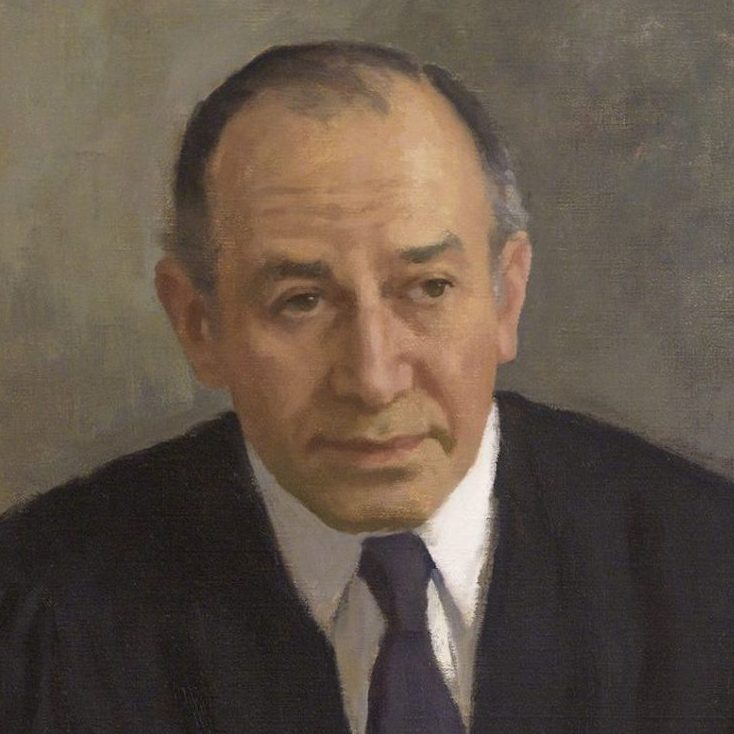

Brennan

-

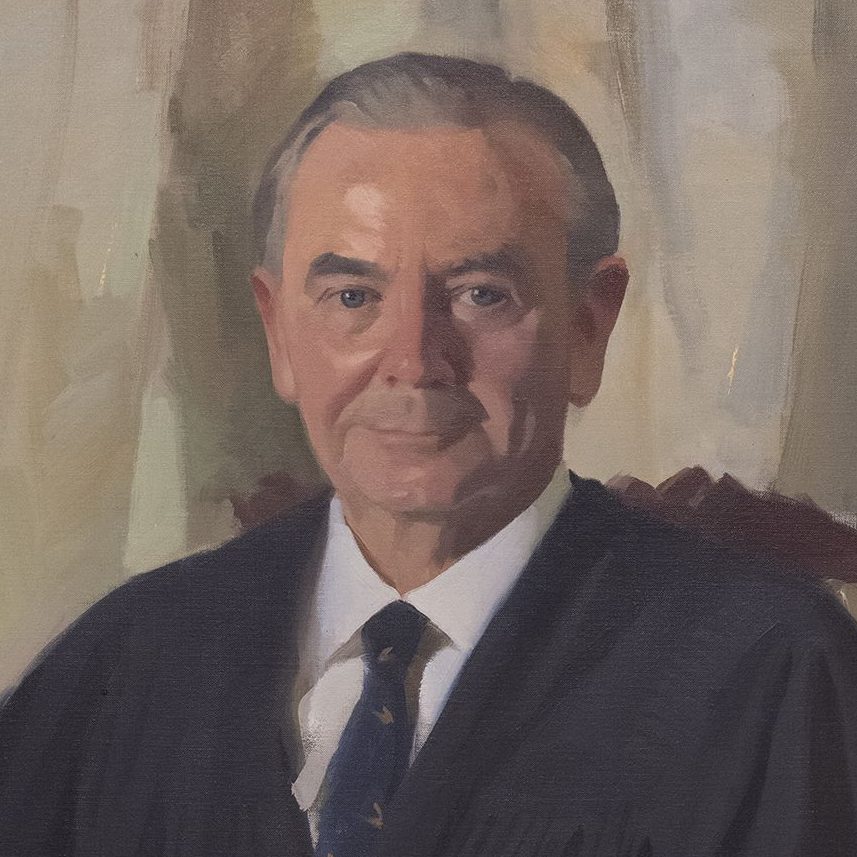

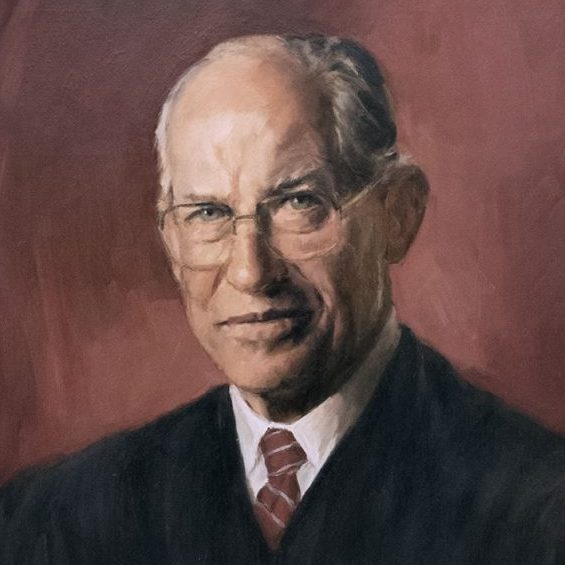

Stewart

-

White

-

Fortas

-

Majority Opinion

Earl WarrenRead More CloseUnder our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State.

-

Concurring Opinion

Potter StewartRead More CloseI have previously expressed the belief that “it is simply not possible for a state law to be valid under our Constitution which makes the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor.” Because I adhere to that belief, I concur in the judgment of the Court.

Discussion Questions

- Had Loving v. Virginia came across the desk of Supreme Court justices in 1957 instead of 1967, do you think the case would have had a different outcome? Why or why not?

- Why is it significant that this Court ruled 9-0 in favor of the Lovings?

- Why did Chief Justice Warren disagree with the argument that state anti-miscegenation laws did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

- How did Loving impact marriage in the United States?

- Why was Brown v. Board of Education (1954) a turning point for advocates of overturning anti miscegenation laws?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Angela Onwuachi-Willig for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Chambers, Julius L. “Race and Equality: The Still Unfinished Business of the Warren Court” in The Warren Court: A Retrospective. Bernard Schwartz ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. 23-24.

Elgoff, Nancy D. “Just One Drop: Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act, Part I.” Jamestown Settlement and the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown. https://www.jyfmuseums.org/Home/Components/News/News/67/

Horwitz, Morton J. The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice. New York: Hill and Wang, 1999.

Livingston, Gretchen and Anna Brown. “Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia.” Pew Research Center. May 18, 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/05/18/intermarriage-in-the-u-s-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia/.

Morello, Carol. “Virginia’s Caroline County, ‘symbolic of Main Street USA’.” The Washington Post. February 10, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginias-caroline-county-symbolic-of-main-street-usa/2012/01/26/gIQAKH0z2Q_story.html

Wallenstein, Peter. “Race, Marriage, and the Supreme Court from Pace v. Alabama (1883) to Loving v. Virginia (1967).” Journal of Supreme Court History 23, no. 2 (1998): 65-86.

Wallenstein, Peter. Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law—An American History. New York: St. Martin’s Press Griffin, 2002.

Featured image: Richard and Mildred Loving by Grey Villet. 1965. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.2013.97?destination=edan-search/default_search%3Freturn_all%3D1%26edan_q%3Dnpg.2013.97.