Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1901)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that affirmed the unrestricted legislative power of Congress in regard to treaties and weakened Native American claims to landholdings.

Background

Following decades of treaty-making with Native American nations, the United States government shifted to policies of assimilation and allotment. The federal government used forced assimilation to limit the power of the tribal councils, leaders that governed Native nations. At the same time, allotment plans, such as the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887, drastically reduced the size of Native reservation lands. The Dawes Act broke up reservations into individual parcels of land to promote private land-ownership, which undermined the communal landholding practices common among Native tribes. It also sold off so-called “surplus land” to non-Native settlers. During the 1880s, Congress also put strict ration programs in place on reservations. These programs attempted to force certain farming and livestock methods on tribes. Native people often resisted such changes, in part because large portions of many reservations were not well-suited for agriculture. Additionally, frontiersmen indiscriminately hunted bison, an important resource for plains tribes, for sport and to pave the way for railroad construction. Food shortages caused by strict rationing, combined with the elimination of the bison population, led to a period of starvation for many tribes on the western frontier. By the turn of the century, the Indigenous population in the United States reached its lowest point—less than 250,000, compared to an estimated eight million in 1492 upon the arrival of European settlers.

In 1892, the Jerome Commission, named for Chairman David Jerome, attempted to change the terms of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. The treaty, signed by the U.S. government and Native tribes including the Kiowa, Comanche, Plains Apache, and Cheyenne, established reservations in western Oklahoma. In exchange for moving off their ancestral land and into these assigned territories, the U.S. government promised to protect the tribes from white settlers. The agreement also required the signatures of three-fourths of the adult Indigenous male population on the reservation for any future land transfers to the U.S. government. In line with the Dawes Act, the Commission wanted to allot the land and sell the remaining parcels to settlers. Tribal leadership, determined “not to sell the country,” told the government representatives to come back in four years once the Medicine Lodge Treaty expired.

The commissioners actively moved forward with their plans to gain the necessary signatures from Native people to alter the treaty terms. By mid-October, Jerome claimed to have over half of the needed signatures. Many Natives asserted the commissioners lied to them during negotiations. Jerome reminded the Native people that, “Congress has full control of you, it can do as it is a mind to with you,” and that “Congress [was] determined to open this country.” It became clear that complying with the terms of the treaty no longer interested the Commission. After returning to Washington, D.C., the commissioners made changes to the agreement without input from tribal councils. Though the final agreement contained mostly counterfeit signatures, the Commission certified the changes and sent the document to Congress. Congress ratified the Jerome Agreement on June 6, 1900 and a year later, President William McKinley declared the surplus lands open to settlement.

Facts

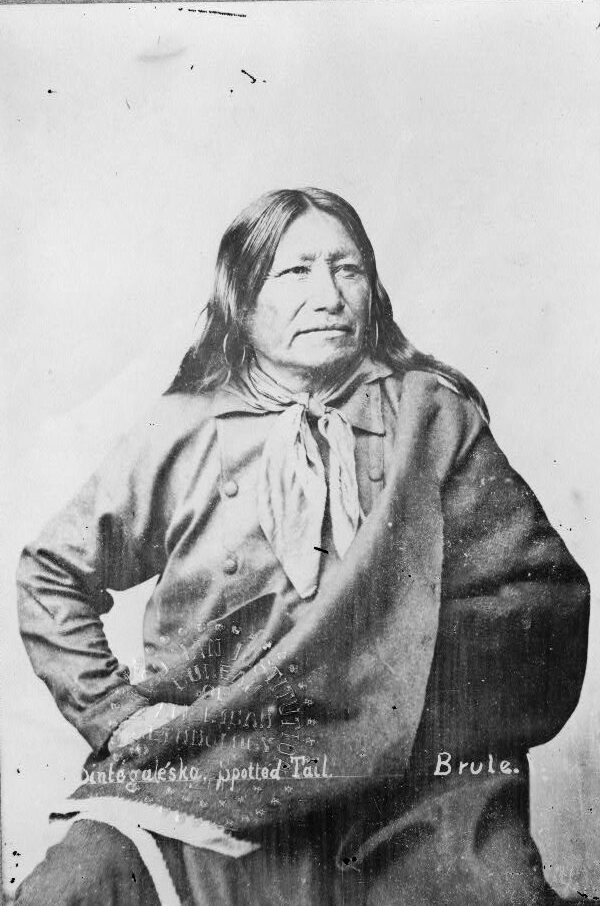

Lone Wolf, a Kiowa chief living in the western Oklahoma reservations, sued the U.S. government for violating the Medicine Lodge Treaty. In the case filed against the Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Hitchcock, Lone Wolf cited the fraudulence of the Jerome Agreement. Additionally, he argued that the federal government violated their Fifth Amendment right of due process under the takings clause. This clause provides that the government cannot confiscate private property without fairly compensating the owner. The Supreme Court for the District of Columbia and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia both sided with the government. Lone Wolf appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1902.

Issue

Does Congress have unrestricted legislative authority to break treaties between the United States and Native Americans?

Summary

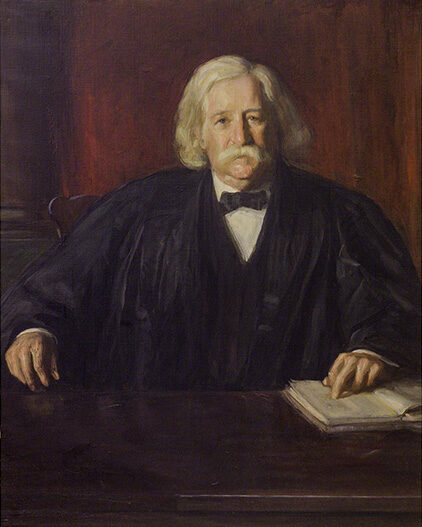

The Supreme Court unanimously held that “it was never doubted that the power to abrogate (repeal laws and treaties) existed in Congress…particularly if consistent with perfect good faith towards the Indians.” The decision affirmed Congress’s authority to modify agreements made with Native Americans. Writing for the Court, Associate Justice Edward D. White cited Beecher v. Wetherby (1877), arguing that Native land belonged to the federal government and the government could do what it wanted with the land. Furthermore, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) had defined Native Americans as “wards” of the government. Therefore, it was Congress’s responsibility to act as the guardian of the land. Overall, the Court affirmed that “Congress possessed full power in the matter,” so “the judiciary cannot question or inquire into the motives.”

Precedent Set

The 1903 Lone Wolf decision affirmed Congress’s plenary power. Though the U.S. government had been violating its treaties with Native Americans for decades, it now had full legal authority to control tribes through Acts of Congress and disregard any established treaties. Moving forward, the federal government trusted Congress to act “in good faith” to administer tribal lands.

Additional Context

Lone Wolf is one of a series of Supreme Court decisions that progressively stripped Native peoples of many important aspects of their land and sovereignty. In U.S. v. Kagama (1886), the Court affirmed Congressional power over crimes committed by one Native American against another. The Kagama decision reinforced the Major Crimes Act of 1885 and provided further evidence that the federal government had switched from negotiating with Native nations and would instead govern them through acts of Congress. During the same Term as Lone Wolf, the Court held in Cherokee Nation v. Hitchcock that Congress had full power over tribal lands. Between 1887 and 1934, the “allotment era,” Kiowa landholdings dropped over 90 percent. The loss of land led to inconsistent income for many Natives, establishing a cycle of poverty that still exists in many communities today. After years of legal battles, the 1955 Indian Claims Commission awarded the Kiowas, Comanches, and Plains Apaches $2 million for lands taken from them illegally.

Meanwhile, the United States also acquired overseas territories. The government applied Congress’s plenary power, as confirmed by Lone Wolf, to U.S. imperialism. Just as Native people were living in the western territories when settlers moved in, there were already inhabitants living in the territories the U.S. gained at the turn of the century. After the Spanish-American War, for example, the United States acquired sovereignty over the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The federal government viewed Native island people as “weak and helpless” dependents who needed to be ruled by a superior power. As Governor of the Philippines, future president and Chief Justice William Howard Taft stated, “it was clear that the Philippine Islands and other American possessions needed the helping and guiding hand of the Americans.” The leaders of the Indian Rights Association who fought on behalf of Lone Wolf recognized these similarities and expanded their goals to include anti-imperialism causes.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Fuller

-

Harlan

-

Brewer

-

Brown

-

Shiras Jr.

-

White

-

Peckham

-

McKenna

-

Holmes Jr.

-

Majority Opinion

Edward Douglass White Jr.Read More CloseWe must presume that Congress acted in perfect good faith in the dealings with the Indians of which complaint is made, and that the legislative branch of the government exercised its best judgment in the premises. In any event, as Congress possessed full power in the matter, the judiciary cannot question or inquire into the motives which prompted the enactment of this legislation.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the federal government wanted to shift away from the policy of treaty-making? How did new policies affect tribal sovereignty?

- What does it mean to act in “good faith”? Do you think Congress acted in “good faith” when it came to adjustments made to reservation land?

- Tribal sovereignty describes Native Americans’ right to govern themselves. Analyze the Court’s reasoning in its unanimous decision regarding Congress’s power. What implications did this have for tribal sovereignty?

- Evaluate the short and long term impacts of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Ezra Rosser for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Comanche Indians on the way to the Great Council on Medicine Lodge Creek, Monday, Oct. 16. Medicine Lodge Kansas, 1867. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/89714364/.

Blackhawk, Ned. The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. Yale University Press, 2023.

Clark, Blue. Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock: Treaty Rights & Indian Law at the End of the Nineteenth Century. University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Fairbanks, Robert A. “Native American Sovereignty and Treaty Rights: Are They Historical Illusions?” American Indian Law Review 20, no. 1 (1995): 141–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/20068787.

Huey, Aaron. “America’s Native Prisoners of War.” Ted.com. TED Talks, 2010. https://www.ted.com/talks/aaron_huey_america_s_native_prisoners_of_war/transcript.

Klein, Christina. “‘Everything of Interest in the Late Pine Ridge War Are Held by Us for Sale’: Popular Culture and Wounded Knee.” The Western Historical Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1994): 45–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/971069.

Kracht, Benjamin R. “The Kiowa Ghost Dance, 1894-1916: An Unheralded Revitalization Movement.” Ethnohistory 39, no. 4 (1992): 452–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/481963.

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903)

“Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock.” Oyez. Accessed July 21, 2025. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/187us553.

Warren, Louis E. “The Lakota Ghost Dance and the Massacre at Wounded Knee.” American Experience, April 16, 2021.

Wilkins, David E. “The U. S. Supreme Court’s Explication of ‘Federal Plenary Power:’ An Analysis of Case Law Affecting Tribal Sovereignty, 1886-1914.” American Indian Quarterly 18, no. 3 (1994): 349–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184741.