Linda Brown

Life Story: 1943-2018

The seven-year-old girl who became the face of Brown v. Board of Education, an educator, and a lifelong activist

Background

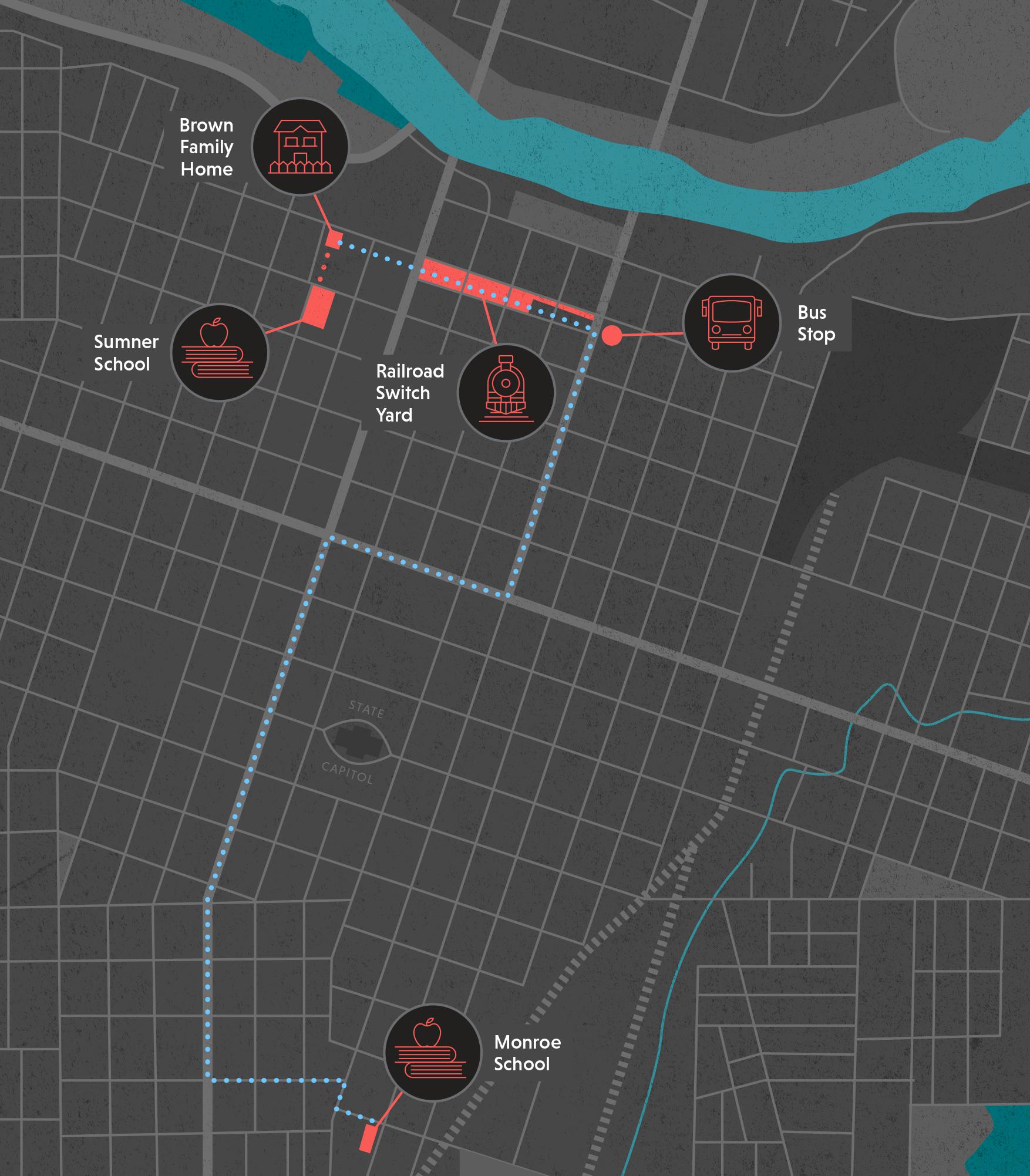

Linda Carol Brown was born on February 20, 1943 in Topeka, Kansas. Her father, Oliver, was a railroad welder and local pastor, and her mom, Leola, was a homemaker. The family lived in a one-story, five-bedroom stone house near the Rock Island switching yard, a busy train junction. While Topeka struggled with racial tensions, it had fewer Jim Crow laws than other parts of the country. The Browns—a Black family—lived in a mostly integrated neighborhood. Linda and her two younger sisters grew up playing with kids from different backgrounds. Even so, a Kansas law allowed cities with populations of over 15,000 people, like Topeka, to segregate their elementary schools. Linda attended the all-Black Monroe Elementary School, while her white friends from the neighborhood attended Sumner. She struggled to understand why they couldn’t all go to school together. “I didn’t comprehend the color of skin,” she remembered, “I only knew that I wanted to go to Sumner School.”

Unlike other places in the country, Topeka’s schools, white and Black, were relatively equal in the quality of education they provided to all students. Linda remembered that Monroe Elementary had “very good teachers” and a “very nice facility.” The problem was distance. Monroe was 21 blocks away from the Brown home. To get there, Linda had to leave the house 80 minutes before class started, walk several blocks, traverse through the dangerous railroad switchyard, cross a busy street, and finally board a bus to take her the remaining two miles. In contrast, Sumner Elementary, an all-white school, was four blocks away.

Brown v. Board of Education

Local activists in the Topeka NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) sought plaintiffs to bring a case against the Board of Education of Topeka. They hoped to challenge the state law that allowed segregated elementary schools. Oliver Brown, Linda’s dad, was recruited by his childhood friend, attorney Charles Scott, to participate in the lawsuit. He joined a group of 12 other plaintiffs representing a total of 20 children. They formed a plan: Each parent would walk to the nearest all-white elementary school and attempt to register their child. In September 1950, Oliver took seven-year-old Linda by the hand and “walked briskly” down the street to Sumner Elementary. He met with the principal while Linda waited in the main office, who worried over the sounds of their rising voices. As expected, the principal refused to register Linda at Sumner. The other 12 parents went to their local all-white schools and, as anticipated, were met with the same result.

The Topeka NAACP filed suit in federal district court on February 28, 1951. Oliver Brown became the lead plaintiff. A three-judge panel unanimously ruled in favor of the board, reasoning that the physical facilities and other measurable factors between the white and Black elementary schools were equal. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, appealed the case. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal, consolidating Brown with four other school segregation cases from around the country (Briggs v. Elliott, Bolling v. Sharpe, Davis v. County School Board, and Belton/Bulah v. Gebhardt). Three years passed between the district court’s ruling and the Supreme Court’s decision. During this time, Oliver became the pastor of a church in the northern part of Topeka, and the family moved. Linda transferred to McKinley Elementary school. She still had to walk a significant distance, and was not allowed to attend the nearby all-white elementary school.

On May 17, 1954, the Court unanimously held that school segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, stating that “separate but equal’…has no place in the field of public education.” Brown marked a major step in overturning the precedent set in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), paving the way for greater equality in the United States. At the same time, it ushered in a new era of racial tensions. Looking back on the decision, Linda remarked that she and her family “lived in the calm of the hurricane’s eye.” Her mom, Leola, said the family was “blessed to live in Topeka. There were some places where things got so bad they had to shut schools down…but not here.” Meanwhile, across the nation, state resistance perpetuated school segregation. Some Southern states refused to comply with the Court’s decision, protesting desegregation with massive resistance tactics. They used pupil placement laws, created Citizens’ Councils, and denied state funding for segregated schools. In March 1956, approximately 100 elected officials representing the former Confederate states signed the Southern Manifesto, a document that asserted Brown was wrongly decided. Some school districts, like in Prince Edward County, Virginia, shut down rather than desegregate, depriving Black students of a public education for years.

As major milestones for the Brown decision approached, Linda worried about being exploited by the press. Around the decision’s 20th anniversary, Linda, now divorced, recalled receiving round-the-clock phone calls and interview requests. For a period of time, aligning with the 25th anniversary in 1979, she started charging a fee for interviews and speaking engagements, at which her lawyer was always present. At the same time, she made a career shift. After several years of working nights as a data processing operator at Goodyear, she went back to school at Washburn and began a public speaking circuit. Linda finished her education at Kansas State University, earning certification in early childhood education. She spent several years teaching preschool for Head Start, a federally funded education program for low-income families. She also taught music lessons and accompanied the choirs at her church in Topeka, where her father once pastored, for over 40 years. She remarried twice: first to Leonard Buckner, and then, after his passing, to William L. Thompson.

Legacy

Linda and her family recognized that the work of Brown was far from finished. In 1979, Linda, along with a larger group of Black parents, reopened the case. They claimed the Topeka school district failed to desegregate schools after Brown. Though the Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal, Linda won her case after a 13-year legal battle. The district court mandated that the school board develop plans to comply with Brown, leading the board to open several magnet schools. Additionally, Linda worked closely with the Brown Foundation after her youngest sister, Cheryl, established it in 1988. As the Foundation’s Program Associate, Linda opened four libraries for preschool children. She also read to children at preschools in Topeka and Lawrence in her “Reading with Ms. Linda” program. The Brown Foundation’s reach expanded far beyond Kansas: The sisters and their mom, Leola, traveled across the country to speak on the significance of Brown.

Linda Brown Thompson died on March 25, 2018 at Lexington Park Nursing and Post Acute Center in Kansas at age 75. The little girl who wanted a shorter walk to school became a symbol of the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education and a champion of civil rights. Her lifelong advocacy and her family’s role in the case have been honored in many ways. Both Monroe and Sumner Elementary Schools were named national historic landmarks. A larger project, Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Park, opened on the grounds of Monroe Elementary on the decision’s 50th anniversary. The park will soon expand to include sites related to the other four cases consolidated in Brown. The town of Manhattan, an hour outside of Topeka, honored the decision by opening Oliver Brown Elementary School in 2021, and hosted Leola, Cheryl, and other family members at the dedication ceremony. Brown v. Board of Education celebrated its 70th anniversary on May 17, 2024.

Discussion Questions

- Why was Topeka a surprising place for Brown v. Board of Education to originate?

- Why did the Topeka NAACP challenge Kansas’s elementary school segregation law if the schools were relatively equal in quality?

- What do you think Linda meant when she said that after Brown she and her family “lived in the calm of the hurricane’s eye”? Explain.

- How did Linda advocate for civil rights after the Brown decision?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Justin Driver for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Adams, Alvin. “5 Pioneers Find Neither Fame Nor Fortune After Case.” Jet. May 21, 1964. https://books.google.com/books?id=AMEDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA17&dq=%22linda+brown+smith%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiIke_4266HAxURD1kFHbdqAC04ChDoAXoECAwQAg#v=onepage&q=%22linda%20brown%20smith%22&f=false.

Burgen, Michelle. “Linda Brown Smith: Integration’s Unwitting Pioneer.” Ebony. May 1979. https://books.google.com/books?id=FWPsX5zvnDUC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=linda&f=true.

Davis, Kelce. “Linda Brown (1943-2018).” Blackpast.org. November 24, 2018. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-linda-1943-2018/.

Dome, AJ. “A wonderful building: Brown family legacy lives on through newest USD 383 school.” The Mercury. August 9, 2021. https://themercury.com/features/a-wonderful-building-brown-family-legacy-lives-on-through-newest-usd-383-school/article_6f04bc96-60bb-527e-9ff1-53a1e4be41c2.html.

Driver, Justin. The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind. New York: Pantheon Books, 2018.

Driver, Justin. “Supremacies and the Southern Manifesto.” Texas Law Review 92; 1053 (2014).

Furlong, William Barry. “The Case of Linda Brown.” The New York Times. February 12, 1961. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1961/02/12/118022735.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

Interview with Linda Brown Smith, conducted by Blackside, Inc. on October 26, 1985, for Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years (1954-1965). Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. http://repository.wustl.edu/downloads/707959237.

Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976.

“Linda Brown on her involvement in Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case.” CSPAN. April 3, 2004. https://www.c-span.org/video/?c4720634/linda-brown-involvement-brown-v-board-education-supreme-court-case.

Montano, Liz. “Wife of Brown v. Board plaintiff recalls landmark decision.” The Topeka Capital-Journal. February 23, 2016. https://www.cjonline.com/story/entertainment/local/2016/02/23/c-j-extra-wife-brown-v-board-plaintiff-recalls-landmark-decision/16600048007/.

Shoemaker, Jane. “Linda Brown Smith is still a symbol—for a fee.” The Wichita Eagle. May 16, 1979.

Slater, Jack. “1954 Revisited: A retrospective look at those who fought for the historic U.S. Supreme Court ruling on school desegregation.” Ebony. May 1974. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jt4DAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA116&dq=ebony+magazine+linda+brown&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwilt93t166HAxUWEVkFHUdNCiwQ6AF6BAgFEAI#v=onepage&q=ebony%20magazine%20linda%20brown&f=true.

Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

“Topeka, Kansas.” Brown v. Board of Education: National Historic Park Kansas. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/brvb/learn/historyculture/topeka.htm.

Featured image: Iwasaki, Carl. Brown Sisters Walk to School. 1953. Photograph. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2014.166.7?destination=/explore/collection/search%3Fedan_fq%255B0%255D%3Dtopic%253A%2522Civil%2520rights%2522%26edan_fq%255B1%255D%3Dname%253A%2522Brown%252C%2520Linda%2522.