Baker v. Carr (1962)

Significant Case

The landmark case that declared unequal representation in legislative districts to be unconstitutional and that the courts have jurisdiction over questions of legislative apportionment

Background

The United States experienced consistent population growth in the first half of the 20th century. People immigrated from all parts of the world, and many migrated within the country from rural areas to urban cities. The growing population, plus the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, created a significant increase in the number of eligible voters. State and local governments were responsible for responding to the needs of these changing demographics. Lawmakers divided states into voting districts, each with a representative in the legislature. Lawmakers created and redrew these districts based on the U.S. Census, a survey of the country’s population conducted every 10 years. When the census was updated, lawmakers adjusted boundaries to account for the growth or loss of a district’s population.

Not all states made these routine adjustments. Some district maps had not been redrawn in decades, causing uneven representation in the legislature. For example, a rural area with 1,000 constituents and an urban area with 10,000 constituents could each be represented by just one lawmaker. Citizens from around the country brought complaints against their state legislatures. They believed that the unequal representation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The complaints were continually dismissed by the court system, which felt that addressing voting districts was an explicit power of the executive and legislative branches. The courts refrained from making decisions that could be perceived as political in nature, or “legislating from the bench,” as it was not their constitutional duty.

Facts

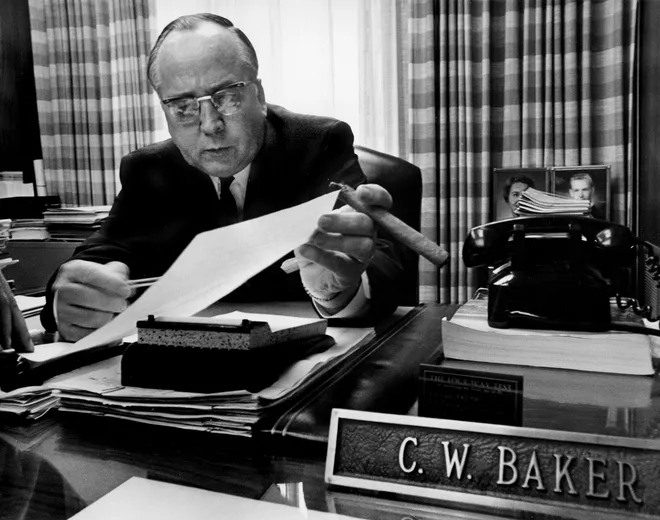

In Tennessee, many people from rural areas moved to cities like Nashville, Knoxville, Chattanooga, and Memphis. Even though the population of the rural areas shrank, their number of representatives stayed the same. The state constitution provided that districts should be reapportioned every 10 years, but the legislature had not updated its apportionment law since it passed its 1901 Apportionment Act. City residents realized that this law was outdated and unconstitutional. They were disproportionately represented compared to rural areas of Tennessee, and their needs were underserved. Charles W. Baker, a Memphis resident, joined other citizens from around the state to sue the state legislature. Votes in Shelby County, where the city of Memphis is, were worth one-eighth of a vote in the less-populated Chester County. In addition to the size of the population—Shelby County had about 627,000 residents, while Chester had around 8,200—they had different racial demographics. In Shelby County, non-white residents made up 36 percent of the population, compared to 13 percent in Chester.

Baker argued that the continued use of the 1901 Apportionment Act violated not only the state constitution, but also the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. On the other hand, the state argued that the case was not justiciable because states had the right to create their federal districts and regulate voting requirements. Baker’s attorneys had to prove that the judicial branch had jurisdiction over concerns about voting districts. They argued that the Tennessee State Legislature was not capable of creating districts that fairly represented the changing population. If the state had not made changes to their legislative districts after multiple census results in the 60 years since the 1901 law, the lawyers argued that it would take a judicial decision to make change. After multiple losses in lower federal courts, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

Issues

- Did the Supreme Court have jurisdiction over questions of legislative apportionment?

- Could the Supreme Court rule on the way states draw their state legislative boundaries?

- Did unequally represented districts violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Summary

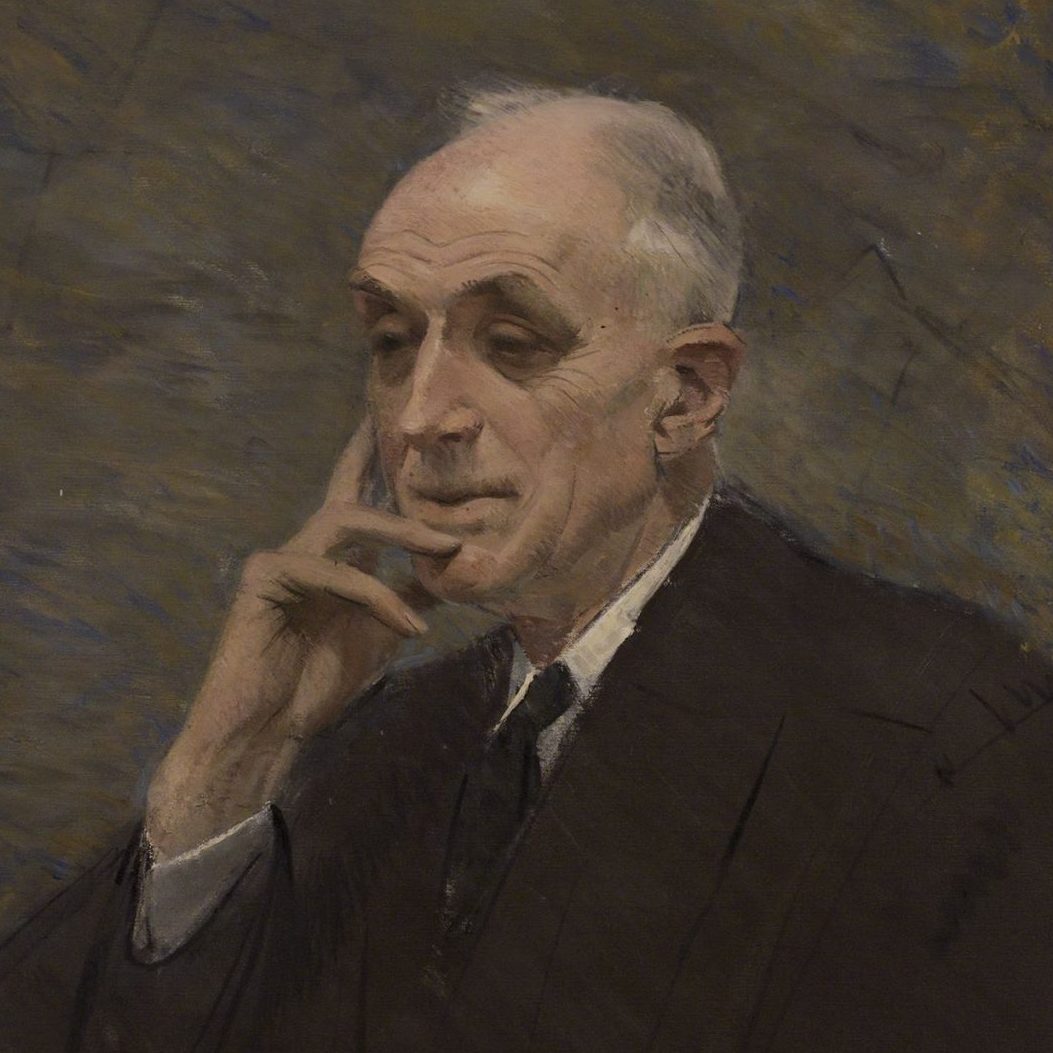

In the 6-2 majority opinion, the Supreme Court held that questions of legislative apportionment were justiciable. In his majority opinion, Justice William Brennan cited previous examples where the Court corrected state administration of laws that violated the rights of its citizens. He held that the lack of reapportionment of legislative districts in Tennessee violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Precedent set

The Baker decision protected individual rights by holding that unequal representation of citizens is unconstitutional and may be reviewed by courts. In 1964, the Supreme Court heard six more cases regarding legislative apportionment in Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, New York, and Virginia. Those cases built upon the Baker decision and created the “one person, one vote” standard used to determine apportionment. This standard meant that no single person’s vote should be weighted more than anyone else’s. By 1966, citizens in 46 states filed suits in apportionment cases using the argument that failing to redraw districts violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Additional Context

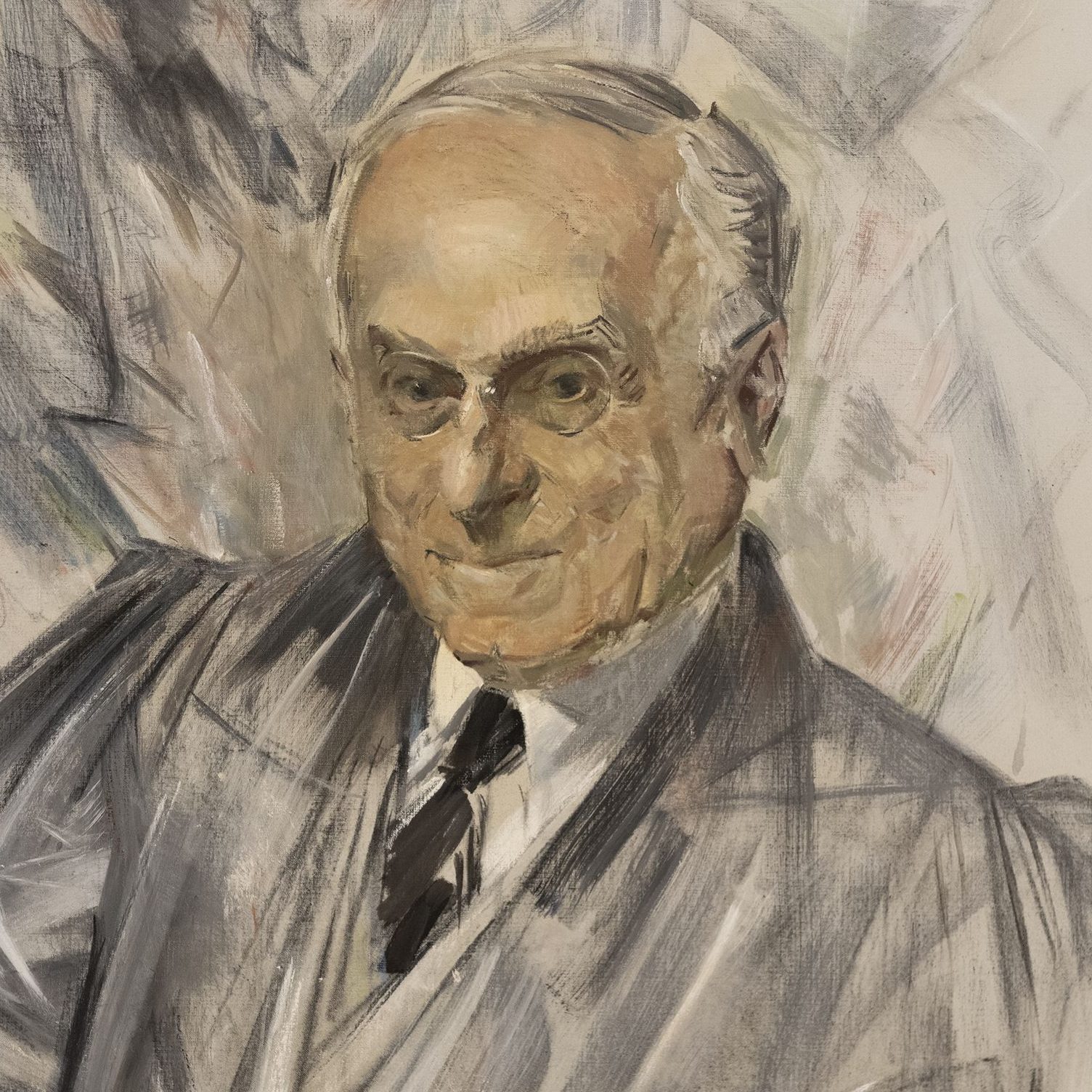

Justice Felix Frankfurter, one of the two dissenters, worried that this case would bring the Court into the “political thicket.” He feared that hearing Baker meant that the Supreme Court was taking an irreversible step to insert itself into political matters where it did not belong. He suffered a stroke less than two weeks after the Court handed down the Baker decision. Visitors to the Justice’s bedside recall him sharing that the outcome of the Baker case was responsible for his medical condition.

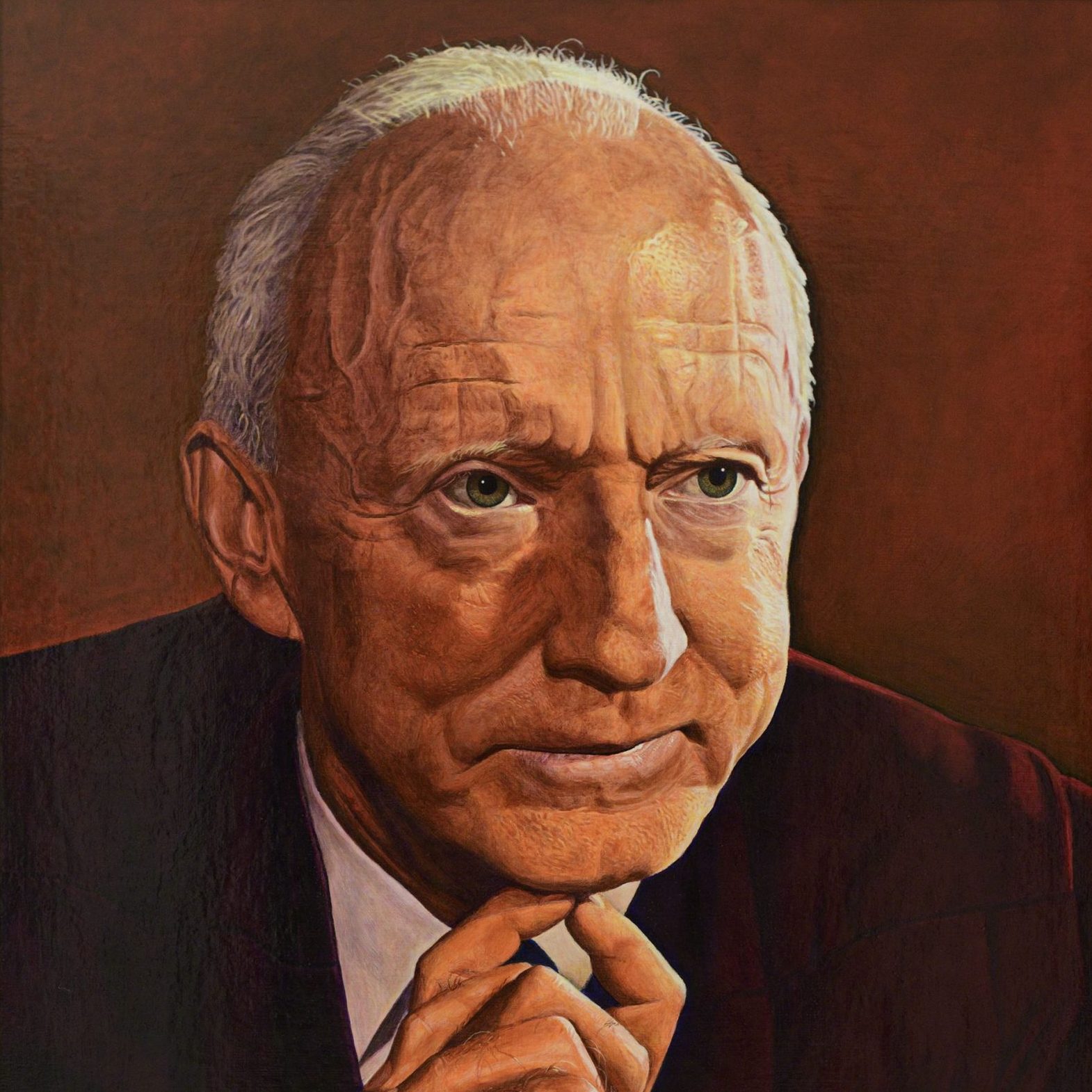

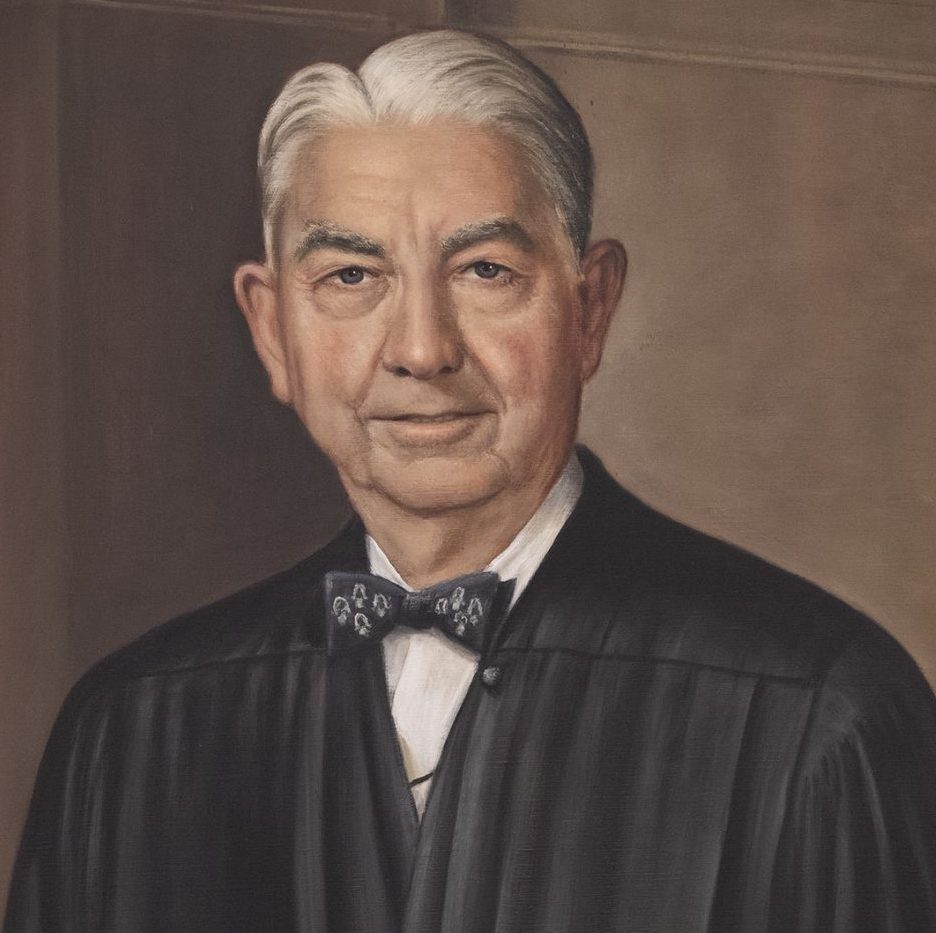

Chief Justice Earl Warren heard several landmark cases during his tenure, including Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Miranda v. Arizona (1966), and Tinker v. Des Moines (1969). These cases all have received significant attention because of the precedents that they set in education, the rights of the accused, and student rights. Yet Chief Justice Warren considered Baker v. Carr, a lesser-known case, the most important of his tenure in the Supreme Court.

Court Opinions

The Court issued a 6-2 decision for Baker.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Warren

-

Black

-

Frankfurter

-

Douglas

-

Clark

-

Harlan II

-

Brennan

-

Whittaker

-

Stewart

Discussion Questions

- How did migration patterns in the United States lead to Baker v. Carr?

- Why were courts hesitant to accept apportionment cases?

- Why was it a problem that Tennessee had not updated its apportionment law in 60 years?

- How did the Baker decision protect individual rights?

- Why do you think Chief Justice Earl Warren considered Baker to be the most important case he heard?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar Helen Knowles-Gardener for her review and feedback.

Knowles, Helen J. May It Please the Court? The Solicitor General’s Not-So-“Special” Relationship: Archibald Cox and the 1963-1964 Reapportionment Cases. 31-3:279-297 (2006).

Terris, Bruce J. Attorney General Kennedy versus Solicitor General Cox: The Formulation of the Federal Government’s Position in the Reapportionment Cases. 32-3:335-345 (2007).

“Baker v. Carr et. al., March 2, 1962 (369 US 186).” Shifting Boundaries: Redistricting in Washington State. Washington State Legislature. https://app.leg.wa.gov/oralhistory/redistricting2/1960s/1962/1962_courtCases.aspx.

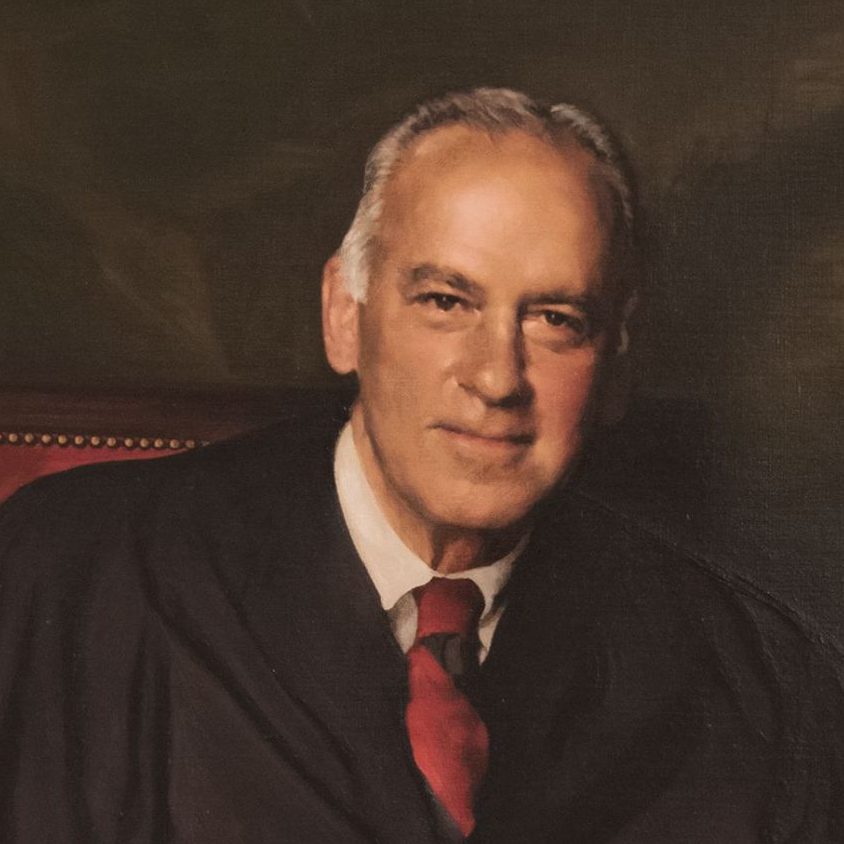

Featured image: C.W. “Charles” Baker, May 1965. The Tennessean. https://www.tennessean.com/picture-gallery/news/2019/07/03/baker-vs-carr-tennessee-case-influenced-supreme-court-gerrymandering/1645090001/.