Ex parte Crow Dog (1883)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that upheld Native American tribal sovereignty but paved the way for an expansion of federal authority over crimes committed in Native territory.

Background

In 1824, the United States government created the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to oversee relations with Native American tribes. As U.S. settlers moved westward to take advantage of the fertile farmland and plentiful natural resources, the government forcibly removed Native Americans from their lands and onto reservations. The government recognized and respected tribal sovereignty in the reservations, allowing Natives to govern themselves with minimal interference from the United States. Over time, the BIA’s mandate increased as the nation expanded further west. By the 1870s, the agency’s focus shifted to assimilation. The BIA also appointed Indigenous leaders who supported the assimilation movement, often leading to internal conflict among tribal leadership.

Facts

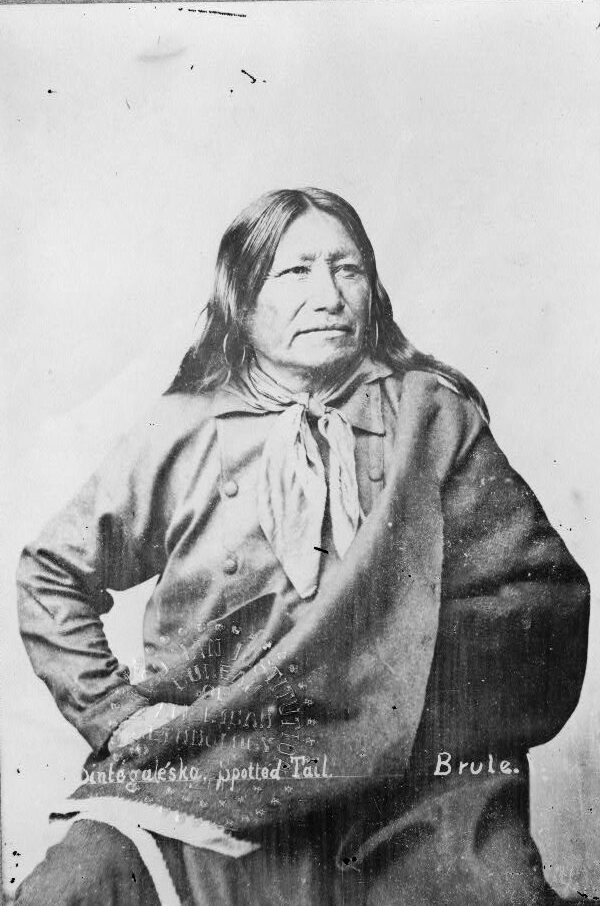

On August 5, 1881 Crow Dog (Kan-gi-Shun-ca), a former captain of the BIA’s Indian police, shot and killed the Brulé Sioux Chief, Spotted Tail (Sin-ta-ga-le-Scka), on the Great Sioux Reservation in present-day South Dakota. Well-known among U.S. government officials, Spotted Tail generally had a good relationship with non-Natives and advocated that the Brulé honor treaty agreements to avoid conflict with the government. Crow Dog shared Spotted Tail’s views on avoiding conflict, but despised his attempts to consolidate control over the tribal decision-making process. Prior to the assassination, Spotted Tail twice removed Crow Dog from his position as police captain. Crow Dog tried unsuccessfully to oust Spotted Tail as chief. A tribal council convicted Crow Dog and ordered Crow Dog’s family to pay Spotted Tail’s family restitution. They paid $600, eight horses and one blanket—a sizable sum. This followed tribal law and allowed for the community to address the incident quickly and restore peace on the reservation. Although Crow Dog paid his debts according to Brulé law, the reservation’s BIA Indian Agent arrested and imprisoned him off the reservation in the Dakota Territory.

A Dakota Territory court arraigned Crow Dog in the spring of 1882. When the trial took place tensions between white settlers and the Sioux remained high. An all-white jury found Crow Dog guilty and sentenced him to death by hanging. Crow Dog claimed that a United States court had neither jurisdiction over his case nor the authority to detain him. According to the treaty, the Sioux Nation held sovereign responsibility for trying his case because the events occurred on Sioux land. He appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States and petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus. The BIA hoped to use Crow Dog’s appeal as a test case to challenge Native American sovereignty. The agency invested significant resources in the case and it reached the Supreme Court within the year, unusually fast.

Issue

Did the Dakota Territory court have jurisdiction to try and convict Crow Dog of murder?

Summary

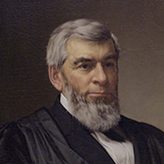

In a 9-0 decision, the Supreme Court concluded that the Dakota Territory did not have jurisdiction over Crow Dog’s case and that his imprisonment was illegal. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Stanley Matthews stated that tribes had self-governing abilities, including in matters of criminal law. The murder of Spotted Tail took place on the Great Sioux Reservation and only involved Brulé Sioux. The Court held that jurisdiction of the United States federal courts did not extend to crimes committed by Natives on Native land if those crimes had already been addressed by the local tribal law. Crow Dog already faced punishment under Brulé custom and the Court reasoned it would not be just to apply “the law of a social state…which is opposed to the traditions of their history, to the habits of their lives.” In the opinion, Justice Matthews cited United States v. Joseph (1876), a case that held Native American tribes had self-governing abilities and title to their own land, rules, and traditions. To give United States law precedence over tribal law in criminal cases, Justice Matthews concluded, “requires a clear expression of the intention of Congress.” In other words, tribes have the authority to govern themselves unless Congress expressly limits or prohibits it.

Precedent Set

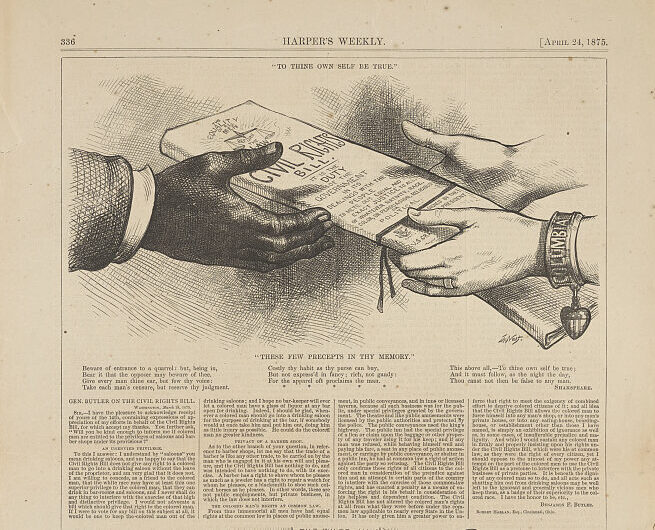

The Court’s unanimous decision reinforced tribal sovereignty in the United States territories. This freedom from federal interference had originally been recognized 50 years earlier by the Cherokee Nation Cases. Both cases—Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832)—involved challenges to Georgia’s authority to apply state laws in Cherokee Nation territory. While the Cherokee Nation decision limited the legal power of Native tribes by classifying them as “domestic dependent nations,” the Worcester case upheld the autonomy of tribal governments. Because federal law regarding tribal sovereignty had not changed since the time of the Cherokee decisions, tribal customs and laws still ruled the affairs of various tribes. While these earlier cases established a framework for tribal sovereignty, Crow Dog tested it in matters of criminal law. The Crow Dog decision also acknowledged that Congress held the power to pass new statutes to override tribal authority as it deemed appropriate.

Additional Context

While the Court’s decision appeared to be a victory for Crow Dog and Indigenous peoples, it triggered a series of legislative actions that progressively restricted tribal sovereignty. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, citing public outrage in response to Crow Dog’s release, pushed Congress to pass the Major Crimes Act of 1885. The act gave federal courts jurisdiction over cases involving any Indigenous person accused of a violent crime. Additionally, it severely limited the power of tribal jurisdiction and undermined the ability of tribes to govern themselves. Furthermore, allotment acts, such as the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887, divided reservation lands into smaller plots. These plots were supposed to be distributed to individual Indigenous families to foster private property ownership. However, most ended up sold to non-Native settlers, drastically reducing Native territory.

By the time the allotment plan ended in 1934, Native Americans had lost much of their reservation lands. About 60 percent of the almost 140 million acres controlled by tribes before allotment transferred out of Native hands. The Sioux Nation challenged the illegal seizure of land, specifically the Black Hills, throughout the 1900s. The Treaty of 1868 guaranteed Sioux authority over these culturally important lands. After being denied compensation in 1920 and 1942, the Sioux brought their case to the newly established Indian Claims Commission in 1946. The Commission ruled in favor of the Sioux, but the U.S. Court of Claims continued to deny compensation based on the previous rulings. In 1978, after Congress amended the Indian Claims Commission Act, the U.S. Court of Claims held that the Sioux were entitled to $17.1 million. The Supreme Court confirmed the decision in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians (1980). The tribes have insisted that they want land returned, rather than money, and the issue remains unsettled.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

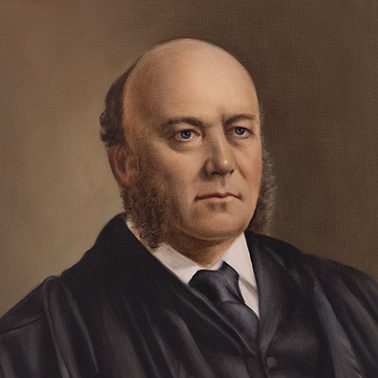

Waite

-

Miller

-

Field

-

Bradley

-

Harlan

-

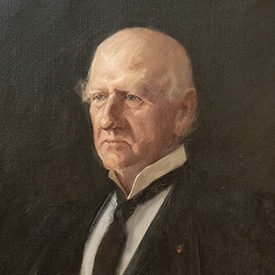

Matthews

-

Woods

-

Gray

-

Blatchford

-

Majority Opinion

Stanley MatthewsRead More CloseThe pledge to secure to these people, with whom the United States was contracting as a distinct political body, an orderly government by appropriate legislation thereafter to be framed and enacted necessarily implies, having regard to all the circumstances attending the transaction, that among the arts of civilized life which it was the very purpose of all these arrangements to introduce and naturalize among them was the highest and best of all — that of self-government, the regulation by themselves of their own domestic affairs, the maintenance of order and peace among their own members by the administration of their own laws and customs.

Discussion Questions

- Why was the principle of tribal sovereignty significant in Crow Dog’s case?

- How did United States policies impact Native Americans over time?

- In what way was the Supreme Court’s decision in Crow Dog culturally sensitive to the Sioux?

- What does this case illustrate about the conflict between the U.S. government and Native American tribes over who has the right to make and enforce laws?

- Compare the short and long-term impacts of the decision in Ex parte Crow Dog.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and history professor Ned Blackhawk for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Jintégaléska?, Spotted Tail–Brule. , None. [Between 1870 and 1881] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/96523328/.

Blackhawk, Ned. The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. Yale University Press, 2023.

Clow, Richmond L. “THE ANATOMY OF A LAKOTA SHOOTING: CROW DOG AND SPOTTED TAIL, 1879-1881.” South Dakota History 28, no. 4 (1998).

Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556 (1883)

“Ex parte Crow Dog.” Oyez. Accessed June 24, 2025. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/109us556.

Franklin, Catharine R. “Black Hills and Bloodshed: The U.S. Army and the Invasion of Lakota Land, 1868–1876.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 63, no. 2 (2013): 26–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24416238.

Harring, Sidney L. “Crow Dog’s Case: A Chapter in the Legal History of Tribal Sovereignty.” American Indian Law Review 14, no. 2 (1988): 191–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/20068289

Harring, Sidney L. Crow Dog’s case: American Indian sovereignty, tribal law, and United States law in the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press, 1994

Justice.gov. “679. The Major Crimes Act—18 U.S.C. § 1153,” February 20, 2015. https://www.justice.gov/archives/jm/criminal-resource-manual-679-major-crimes-act-18-usc-1153.

Kliewer, Addison, Miranda Mahmud, and Brooklyn Wayland. “‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man’: Remembering the Stories of Indian Boarding Schools,” 2021. https://www.ou.edu/gaylord/exiled-to-indian-country/content/remembering-the-stories-of-indian-boarding-schools.

NEVILLE, ALAN L., and ALYSSA KAYE ANDERSON. “THE DIMINISHMENT OF THE GREAT SIOUX RESERVATION: TREATIES, TRICKS, AND TIME.” Great Plains Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2013): 237–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24467580.

Pipestream, F. Browning. “The Journey from Ex Parte Crow Dog to Littlechief: A Survey of Tribal Civil and Criminal Jurisdiction in Western Oklahoma.” American Indian Law Review 6, No. 1. (1978). https://doi.org/10.2307/20068050.

“Story of the Battle – Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (U.S. National Park Service),” 2025. https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.htm.