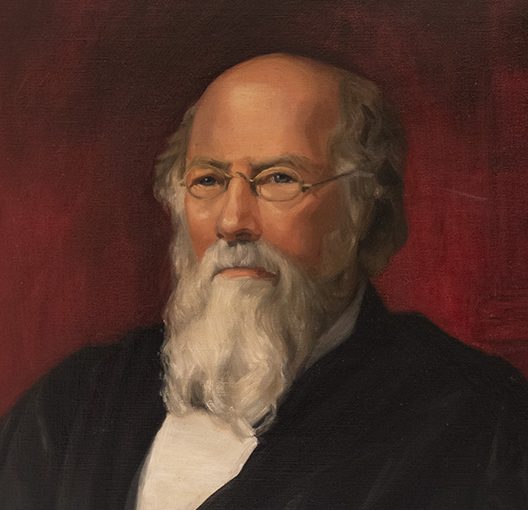

Stephen J. Field

Life Story: 1816-1899

A bold and adventurous attorney who ventured to California for the gold rush before his jurisprudence laid the foundation for laissez-faire constitutionalism during his service as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A bold and adventurous attorney who ventured to California for the gold rush before his jurisprudence laid the foundation for laissez-faire constitutionalism during his service as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Background

Early Life

Stephen Johnson Field was born on November 4, 1816, to Submit Dickinson Field and David Dudley Field I in Haddam, Connecticut. He was the sixth of nine children. Stephen’s parents both descended from New England Puritan families and had ties to the Revolutionary War. Known to be a stern, Protestant minister, his father also authored historical books. His mother taught school until she married. The Field family lived in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Several of Stephen’s siblings became significant historical figures, including three of his brothers: David Dudley Field Jr., an accomplished attorney who argued several cases before the Supreme Court; Cyrus West Field, the businessman whose company laid the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858; and Henry Martin Field, a clergyman and travel author. At 13 years old, Stephen was sent to the Ottoman Empire with his older sister, Emilia, and her husband, Reverend Josiah Brewer, for mission work. Stephen returned from the two-and-a-half-year excursion with an adventurous spirit that remained with him his entire life.

After his travels, Stephen enrolled at Williams College in Massachusetts. He graduated at the top of his class in 1837 and moved to New York City, where he apprenticed to his brother, David Jr., to study law. He continued his studies by reading law with attorneys in Albany, the state’s capital. Stephen passed the bar in 1841 and returned to the city to practice law with his brother. In 1849, however, the exciting news of the California Gold Rush drew him to the West.

Gold Rush

Stephen Field, now 33, joined the wave of migrants searching for gold in California. He found the idea of “going to a country comparatively unknown and taking part in the fashioning of its institutions” to be “attractive.” After the six-month sail to San Francisco, he ventured north to Yuba County, California. Stephen and other early settlers organized the town of Marysville. His fellow townspeople elected him to be the city’s first alcalde, a Mexican office that combined the roles of mayor and judge. He arrived not long after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the recent war with Mexico. As an original settler and alcalde, Stephen integrated the existing Mexican laws and traditions as well as treaty agreements with American laws and procedures into the town.

California Representative and Judge

Once Marysville established an American-style government, Stephen’s role as alcalde ended and he opened a successful law practice. A fiery and tenacious attorney, Stephen did not avoid controversy. After a particularly hostile courtroom incident, California District Judge William Turner sentenced Stephen to two days imprisonment, fined him $500, and attempted to have him disbarred. Stephen appealed the decision to the California Supreme Court. He argued that his constitutional liberty to pursue lawful employment could not be denied without a hearing. The court sided with Stephen and he retained his right to practice law.

Stephen helped shape California’s governmental institutions for over a decade. In 1850, his fellow Californians elected him to a two-year term in the California legislature. As a lawmaker, he helped to pass key legislation that laid the foundation for California’s government. Still angered by Judge Turner’s attempt to get him disbarred, Representative Field succeeded in having Turner’s judgeship relocated to a remote part of California.

Five years later, he successfully ran for a seat on the three-judge California Supreme Court. During his time on the court, he met and married Sue Virginia Swearingen on June 2, 1859. A few months later, Chief Judge David Terry killed Senator David Broderick, one of Field’s best friends, in a duel. Terry resigned in shame, and Stephen assumed his position as Chief Judge of California. Terry made numerous threats against Field for years. Decades later, Field and Terry encountered each other at a California train station during Stephen’s time as an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court. Terry slapped Field and, believing Justice Field to be in danger, a U.S. Marshal shot and killed Terry.

During its early years, the California Supreme Court handled numerous cases involving land titles and mineral rights arising from differences between Mexican and American law. In Biddle Boggs v. Merced Mining Company (1859), for example, Judge Field authored the court’s opinion, which sided with the landowner. The Merced Mining Company established a mine on land owned by John C. Frémont, a wealthy explorer and politician. This was common practice under Mexican law, which held that mineral rights belonged to the government, not the landowner. Frémont filed a case in the California Supreme Court, which later ruled in his favor. The Biddle Boggs decision proved to be a significant blow to Field’s popularity in California, as many interpreted it as favoring a wealthy landowner. Losing the common man’s faith would later affect his long-term political goals, as would his stubborn personality and firmly held beliefs.

The Supreme Court

In 1863, Republicans in Congress looked to increase Union support during the Civil War. They created a new seat on the Supreme Court of the United States to represent the judicial circuit that included California and Oregon. Though there was no requirement that the seat go to a westerner, Judge Field received the congressional delegation’s unanimous recommendation. As a strong Union supporter, a westerner, and a Democrat, Judge Field was an attractive candidate to Republican President Lincoln, who appointed him on March 6, 1863. Associate Justice Stephen J. Field took his oath of office on May 20. The Fields moved to Washington, D.C., where Sue embraced her role as the wife of a Justice, hosting elegant gatherings for fellow government wives and families. Justice Field spent several months each year in California for his circuit-riding duties. Thankfully, the completion of the transcontinental railroad made this journey significantly easier for Stephen after 1869. Instead of spending months on a ship via the Panama Canal, the journey took approximately four days by train.

In the midst of the Civil War, the Supreme Court heard cases related to loyalty to the Union. One of the first cases he presided over, United States v. Greathouse (1863), was a treason case tried before a federal jury in California. Under a broad interpretation of treason, Justice Field found guilty a group of men who conspired to aid the Confederacy. He sentenced them to the maximum penalty allowed by law: a $10,000 fine, forfeiture of all enslaved people, and 10 years in prison.

As a jurist, Justice Field’s fierce protection of liberty is a hallmark of his long tenure on the Court. After the Civil War, for example, Stephen wrote for a divided Court in the Test Oath Cases (1867) that federal and state loyalty oath laws violated “liberty of profession.” These statutes, designed to keep power from Confederate soldiers and sympathizers, required people to pledge their undivided loyalty to the Union—and swear that they had never been disloyal—in order to vote or work in government jobs (and even some private sector ones). For Field, the right to choose a lawful profession remained an inherent, natural right protected by the Constitution.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, allowed Justice Field to strengthen his argument surrounding liberty of profession. He believed that the Reconstruction Amendments, particularly the Fourteenth, fundamentally altered the authority of both the federal and state governments. His broad interpretation of the amendment laid the foundation for the concept of substantive due process—the theory that the Due Process Clause protects “inalienable rights” not explicitly listed in the Constitution. Stephen demonstrated this belief in his dissent in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873). Rejecting the theory that the Fourteenth Amendment created an implied right to choose a profession, the majority upheld a law that required butchers to practice their trade in a central slaughterhouse. Four dissenters disagreed, with Field arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections extended beyond protecting the rights of formerly enslaved people and extended its guarantee of privileges and immunities to other rights, such as “the right to pursue lawful employment in a lawful manner” for all citizens. Ironically, that same Term, Field joined the majority in Bradwell v. Illinois that denied Myra Bradwell the right to obtain an Illinois law license. Women did not enjoy the same liberty of profession as men. Field’s reasoning was more consistent in his dissent in Munn v. Illinois four years later, when the Court affirmed that states could regulate private business that served the public interest. Stephen argued instead that the Due Process Clause should protect businesses from regulation.

Justice Field believed limiting the federal government’s authority to the enumerated and implied powers of the Constitution protected individual liberty. It was not the federal government’s job to protect personal freedom. State governments also possessed their own police power to regulate health, safety, morals, peace, and good order. Neither institution should infringe on the other’s power. While Congress intended the Fourteenth Amendment to protect Black Americans from state discrimination, Stephen’s staunch support of federalism fostered inconsistent jurisprudence on race-based laws. For example, Field dissented in Strauder v. West Virginia (1880) when the majority held a West Virginia law declaring only white people could serve on juries unconstitutional. In his dissent, Field wrote that the Fourteenth Amendment extends only to civil rights—jury service was a political right and thus under the jurisdiction of the states. A few years later, Stephen authored the Court’s holding that the Equal Protection Clause did not apply to interracial couples in Pace v. Alabama (1883), since both parties were punished equally under the Alabama law. For Field, federal involvement in either case was a violation of federalism.

Justice Field later clarified the parameters of a state’s authority over personal jurisdiction in the landmark Pennoyer v. Neff (1878) case. The majority opinion established that a state’s power to exercise its authority is confined to its borders. Field’s opinion became precedent that guided other cases for over 70 years.

While serving as a Circuit Justice over the Tenth Circuit, Justice Field rejected several California laws aimed at Chinese immigrants. Between the end of the Civil War and 1882, nearly 300,000 Chinese laborers entered the country. A growing number of job opportunities in mines and railroads attracted workers to the western United States. Anti-Chinese sentiment grew as a result of racism and competition for work. In his In re Ah Fong (1874) circuit opinion, Stephen declared a deportation law aimed at Chinese women unconstitutional for violating the Burlingame treaty and the Due Process Clause. Four years later, in Ho Ah Kow v. Nunan (Queue Case), he found a San Francisco ordinance allowing sheriffs to cut off queues a violation of the Equal Protection Clause because it only affected Chinese men. In both cases, California exceeded its state authority and passed laws that interfered with the federal authority to make treaties and enforce the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1882, Congress responded to the xenophobia by passing the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended Chinese immigration to the U.S. for 10 years. The Scott Act (1888) strengthened it by barring the re-entry of all Chinese laborers. Chae Chan Ping, a resident of the United States since 1875, obtained the proper paperwork to return to the United States under the act before leaving for Hong Kong in 1887. When he tried to return, six days after the passage of the Scott Act, U.S. customs detained him. Seeming to reverse course, Justice Field wrote the unanimous 1889 opinion that upheld the constitutionality of the Scott Act and barred Ping and all other Chinese laborers from reentering the United States. The opinion affirmed Congress’s authority to regulate immigration.

Stephen Field continued his interest in politics despite serving on the Supreme Court bench. He unsuccessfully ran for the Democratic nomination for President in 1880 and 1884. Though the Pacific Club Set supported him, his unpopular land grant opinions and the appearance of his apparent preference for business elites did not make him popular with the majority of California voters. They also failed to understand the reasoning in Justice Field’s Chinese immigrant opinions. Angered and confused by his failure to come close to securing the nomination, Stephen believed “some old enemy whom I have probably given a just judgment” swayed the media against him.

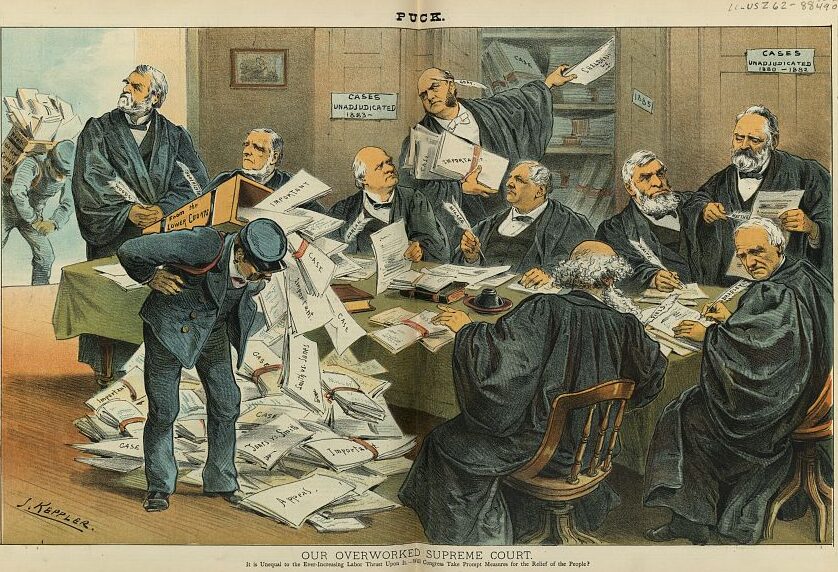

In the final decade of Stephen’s career, the Supreme Court took up several significant issues involving antitrust law, income tax, and segregation. As the composition of the Court changed, so too did their definition of liberty and the authority of the federal government. For the first time in his career, Justice Field found himself consistently in the majority. Late in 1884, the Court heard United States v. E.C. Knight Co., which raised questions about manufacturing monopolies and the Sherman Antitrust Act. In an 8-1 decision, the Court affirmed that manufacturing monopolies were legal under the act. The decision limited the federal government’s power to break up large trusts. A few months later, the Supreme Court also declared unconstitutional the Wilson-Gorman Act, which imposed a federal income tax on personal income. Justice Field’s Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. concurrence argued that the income tax act represented class legislation and an assault on wealth. The Court’s decisions in these cases marked the beginning of the laissez-faire economic era, which lasted until 1937 when the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish upheld a state’s minimum wage law. The decision marked a shift away from precedents that struck down state-based economic regulations, such as in Lochner v. New York (1905).

Legacy

Associate Justice Stephen J. Field retired from the Supreme Court of the United States in 1897 after 34 years on the bench. The first Justice from California and the only Justice to occupy the 10th seat, he brought a brash and innovative spirit to Washington, D.C., with mixed results. His tenure surpassed the previous longest-serving justice, Chief Justice John Marshall, and his service spanned eight Presidents and three Chief Justices. Justice Field authored 544 opinions and numerous influential dissents. As an intellectual leader on the Court, he helped advance the theory that the Fourteenth Amendment created an implied right of entrepreneurial liberty. Stephen died in 1899, just as fellow justices began applying his expansive interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, a theory known as liberty of contract. This theory guided the Court until 1937 and has since regained popularity. Justice Field is considered the father of substantive due process and is remembered for his forceful personality and his bold and brilliant thinking.

Discussion Questions

- How did Stephen’s personality affect his career?

- How did Stephen Field’s experience in California affect his devotion to property rights?

- Why do you think Justice Field dissented in the Slaughter-House cases but was part of the majority in the Bradwell case?

- Consider the final words of Justice Field’s Queue Case opinion were: “thoughtful persons … hope that some way may be devised to prevent [Chinese] immigration.” How might you explain Justice Field’s differing opinions regarding Chinese immigration?

- Which of Justice Field’s opinions or dissents do you think is the most important? Explain.

- How did Justice Field’s interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment impact the evolution of constitutional law in the United States?

- How could Justice Field be considered both innovative and a product of his time period?

- What are three adjectives you would use to describe Justice Stephen Field?

Extension Activities

-

Imagine you were writing a biography of Justice Stephen Field. What would you title the book? Which three events or cases do you believe are the most important to include? Explain your choices.

-

Compose a eulogy or obituary for Justice Field.

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and professor Dr. Paul Kens for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Portrait of Justice Stephen J. Field. Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Chae Chan Ping v. U.S. (Chinese Exclusion Case), 130 U.S. 581 (1889)

Cushman, Clare, ed. “Stephen Field: 1816-1899.” The Supreme Court Justices of the United States: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2013.

Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866)

Field, Stephen J. Personal Reminiscences of Early Days in California, With Other Sketches. 29-1:22-119 (2004).

Kens, Paul. Justice Stephen Field of California. 33-2:149-159 (2008).

Kens, Paul. Justice Stephen Field: Shaping Liberty from the Gold Rush to the Gilded Age. (1998).

Mining Company v. Boggs, 70 U.S. 3 Wall. 304 304 (1865)

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1876)

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883)

Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714 (1878)

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1872)

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)