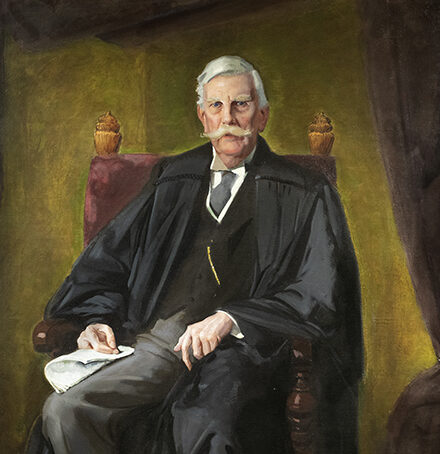

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Life Story: 1841-1945

The Boston native, Civil War soldier, and Associate Justice whose legal theories revolutionized modern understanding of the law.

Background

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was born in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts, on March 8, 1841. His father, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., was a well-known medical innovator, Harvard anatomy professor, and popular writer. His mother, Amelia Lee Jackson, was the daughter of a prominent Boston attorney who became a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. The couple had three children—Wendell, the oldest, and his younger siblings Amelia and Edward. The Holmes family lived a comfortable lifestyle, complete with a summer home in the countryside of western Massachusetts, and enjoyed connections with Boston’s elite families. Growing up in Boston society fueled a lifelong, insatiable thirst for knowledge that Wendell pursued his entire life. At the time, Boston was one of the nation’s premier intellectual and cultural hubs. Having a famous father and well-to-do mother put Wendell at the center of the activity. The family often crossed paths with prominent politicians, scholars, and writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose work became a lifelong inspiration for Wendell.

Wendell’s childhood schoolmaster—later to be his father-in-law—remarked that he had a “love of study remarkable for his age.” At school, he learned Latin, Greek, ancient history, and mathematics; the standard curriculum for a Harvard-bound student. As a Boston boy with high social standing, it was inevitable that he would continue his education at that prestigious college in nearby Cambridge, Massachusetts. Plus, it was a family tradition—both his father and grandfather were Harvard graduates. Wendell enrolled in the fall of 1857, when he was 15 years old. Handsome, charismatic, intelligent, and from a well-known family, Wendell became popular with his classmates and was invited to join Harvard’s most exclusive finals clubs. He enjoyed the companionship of college, reflecting in a letter to a friend that “it’s delightful—one night up till one at a fellow’s room, the next cozy in your own.” The academics, however, left something to be desired. As someone who spent his youth surrounded by some of the nation’s foremost thinkers, Harvard’s curriculum, which heavily relied on rote memorization, bored Wendell. Though he was a diligent and serious student, he was not afraid to challenge the status quo. He debated with his professors, and as the editor of Harvard Magazine, wrote and published articles criticizing the university’s teaching methods. Wendell’s defiance created enough disturbance to prompt the school’s president to send letters home to Dr. Holmes on more than one occasion.

Wendell’s best friend at Harvard, Pen Hallowell, was from a Philadelphia Quaker family that volunteered its home as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Listening to Pen’s stories about helping people escape slavery gave Wendell a new perspective to consider as the nation teetered on the brink of civil war. As a manufacturing center, Boston’s economy relied on Southern cotton. In light of this business interest, many of the city’s elite, including Dr. Holmes, were willing to tolerate slavery as the price of preserving the Union. Meanwhile, his mother was a staunch abolitionist. When the Civil War began in 1861, however, Dr. Holmes abruptly changed his mind and became an outspoken opponent of slavery and supporter of the the Union cause. Wendell wholeheartedly agreed. One of the first in his class to enlist, Wendell abruptly left Harvard without permission or notice. A few months later, the school reluctantly allowed the student soldiers to return, take their exams, and graduate on time, but Wendell ignored the invitation. President Cornelius Felton reached out to Dr. Holmes—again—to report that Wendell “had not rejoined his class since he was relieved of his duty.” Ultimately, he returned for graduation and, like his father, received the award for Class Poet.

Wendell then served for three harrowing years with the Massachusetts Twentieth Volunteers, sometimes called “The Harvard Regiment,” a reference to the number of officers who attended the college. He was severely wounded on three separate occasions, twice almost fatally, later reflecting that “it almost humiliates me to think of my luck.” He received a hero’s welcome during his recoveries at his parents’ home in Boston. After his first injury at the Battle of Balls Bluff, his mother counted 133 visitors, including the abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner, Harvard President Cornelius Felton, and several young ladies who were eager to greet the handsome war hero. At the battle of Antietam, he was shot through the neck and was lucky to survive. By the time his enlistment ended in July 1864, Wendell achieved the permanent rank of captain. His regiment had been decimated and he had seen many close friends die.

Career

With his war years behind him, Wendell returned home and spent the next two years at Harvard Law School. He continued to be a serious student and a voracious reader. When he was 21, he started keeping track of everything he read, a habit he maintained throughout his life. Upon his death in 1932, the list exceeded 4,000 books, covering an astonishing range of subjects: ancient history, religion, science, sociology, poetry, economics, novels, even murder mysteries. He read books in multiple languages, including Latin, Greek, French, German, and Italian. After his graduation in 1866, he spent several months travelling abroad, the first of many European adventures. Wendell passed the Massachusetts bar exam and joined a Boston law firm in 1867, where he practiced as a trial lawyer for the next 15 years. He regularly represented railroads, banks, and other commercial entities in Massachusetts courts and in 1878, he argued an admiralty case at the Supreme Court of the United States. In the midst of his young career, he married Fanny Bowdich Dixwell, daughter of his childhood schoolmaster, on June 11, 1872. His parents knew it was a match—Fanny and Wendell were lifelong friends and “were entirely devoted to one another.” They were married for 57 years with no children. Fanny had a playful sense of humor and liked to play practical jokes on her husband.

Always craving intellectual stimulation, Wendell sought opportunities to engage with law in the academic world. In addition to his full-time practice, he became coeditor of the American Law Review and lectured at Harvard. His scholarly work earned him an invitation to speak at the prestigious Lowell Institute lectures in 1880. Wendell’s ideas broke with traditional views. He pioneered legal realism, the concept that law was “a living, evolving organism that changed with society’s needs.” He published the lectures into a book, The Common Law, which quickly became standard literature in the law community.

The Common Law earned Wendell a reputation as a serious legal scholar, launching the next phase of his career. Following the book’s release, Harvard appointed him as a professor of law in the fall of 1881. Professor Holmes’ tenure, however, was short-lived. After barely a year teaching at his alma mater, the Governor appointed him to serve as a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, the state’s highest court. The appointment, Wendell described, was “a stroke of lightning which changed the course of my whole life.” He spent the next 20 years on the bench—including an appointment to the chief justiceship in 1899—and authored over 1,000 opinions.

The Supreme Court

Between The Common Law and his time on Massachusetts’ highest court, Wendell’s name entered prominent national conversations. When Justice Horace Gray died, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Wendell to fill the seat on the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed Justice Holmes’ appointment on December 4, 1902, just two days after the nomination. Wendell and Fanny cleaned out the family home in Boston and moved to Washington, D.C. It was his first time in the nation’s capital since his oral argument in 1878. Justice Holmes served for 29 Terms with the Court under four Chief Justices. He published over 975 opinions, including 30 concurring opinions and 72 dissents. His wit, brevity, and concise writing style distinguished his opinions.

Rights

During World War I and the First Red Scare, the Court heard several challenges to the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917, which criminalized any speech or activity that interfered with the war effort. Justice Holmes wrote for the Court and held firmly that the government should not interfere with the right to free speech. In the 1919 Schenck v. United States decision, Justice Holmes wrote for the unanimous Court that “words which, ordinarily and in many places, would be within the freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment” may come under scrutiny if they suggest “a clear and present danger” to the country. The “clear and present danger” test remains in use today. Holmes did not believe the test applied, however, to Abrams v. United States, which the Court heard the same year. While the majority held that pamphlets issued by Jacob Abrams urging workers at a munitions factory to strike violated the Espionage Act, Justice Holmes dissented, arguing that the content did not intend to interfere with the U.S. war effort against Germany. He disagreed again with the Court’s application of the clear and present danger test in Gitlow v. New York (1925). The majority upheld the conviction of Benjamin Gitlow for publishing material with intent to overthrow the government, arguing that Gitlow’s words embodied “the language of direct incitement.” Justice Holmes countered this notion in his dissent, stating that “every idea is an incitement. The only difference between the expression of opinion and incitement…is the speaker’s enthusiasm for the result.”

Contrary to his opinions protecting free speech, which would become the cornerstone of First Amendment law, Justice Holmes based some of his opinions on prevailing stereotypes and social prejudices that are now discredited. Regarding race, he consistently sided with the majority on maintaining the “separate but equal” precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Later in his career, Holmes also wrote a notorious opinion that reflected the popular eugenics movement, upholding the legality of a Virginia law that required mentally ill patients to be sterilized in Buck v. Bell (1927). Several cases, though, also opened Justice Holmes’s eyes to the injustice and discrimination experienced by African Americans under segregation. In Moore v. Dempsey (1923), he wrote a landmark decision upholding the rights of 12 Black men hastily convicted of murder in trials with little regard for their justice and constitutional rights.

Commerce and Business

At the turn of the 20th century, the Justices frequently reviewed cases involving the power of the states and the federal government to regulate commerce and business activity. Though personally skeptical of laws that aimed to protect workers and consumers, Justice Holmes, as a believer in judicial restraint, strongly dissented from the Court’s repeated decisions overturning such legislation. Justice Holmes was especially cautious about the Fourteenth Amendment, which was created to extend rights to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. When the Court struck down a New York law setting maximum work hours for bakers in Lochner v. New York (1905), Holmes criticized the majority’s application of the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. According to the majority, the freedom to enter into a contract fell under the Constitution’s prohibition of any government actions that interfered with “life, liberty or property without due process of law.” Here, Justice Holmes believed the majority overextended the Fourteenth Amendment. The opinion, he argued, advanced laissez-faire economic theories at the expense of a legislature’s right to enact laws as it saw fit to respond to economic problems. His famous dissent in Lochner asserted that “a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory…It is made for people of fundamentally different views.”

Justice Holmes was also cautious about overzealous attempts by the government to control the national economy for doubtful ends. Under the direction of President Roosevelt, the Department of Justice prosecuted large corporations under the Sherman Antitrust Act, which had been largely unenforced since Congress passed it in 1890. Justice Holmes dissented in the widely-publicized 1904 Northern Securities case, where a 5–4 majority held that the merger of two of the largest companies violated antitrust law. He believed that the merger was not illegal, or in itself harmful to the economy. The President, frustrated that Holmes did not back his trust-busting agenda, allegedly seethed that he “could carve out of a banana a judge with more backbone!” The dissent led to a falling out between Justice Holmes and President Roosevelt, who had selected him for the Court. It reminded the nation that justices are part of an independent judiciary, not political tools for the presidents who appointed them.

Off the bench, Wendell enjoyed a grand lifestyle filled with creature comforts, international travel, and plenty of reading. Wendell and Fanny invested in $13,357.44 (about $400,000 today) worth of renovations into their D.C. home, including a library with enough built-in shelves to house Wendell’s four tons of books. Their monthly living expenses amounted to double the average American’s annual income: they employed a full house staff and stocked the house with champagne, fine cigars, and other luxury treats like marmalade and candies. The couple enjoyed summers at their second home in Beverly Farms, and Wendell took several trips to Europe throughout his life.

Legacy

Justice Holmes retired from the Supreme Court on January 12, 1932 after 29 years of service. At 90, he was the oldest person to serve as a Justice. He did not miss a single session of court until 1928, 25 years into his tenure, when his age finally began to slow him down. From the time he volunteered for the Union Army in 1861, he became a dedicated public servant who achieved a well-known and respected status throughout the country. After suffering complications from pneumonia, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. died at his home in Washington, D.C. on March 6, 1935, two days shy of his 94th birthday. His life’s work continues to impact the legal world. More than 150 years after its publication, The Common Law is still taught to law students around the country. Many of Justice Holmes’ dissents were later cited in majority opinions and became the law of the land.

Discussion Questions

- How did growing up in Boston influence Wendell?

- Why did Wendell become passionate about the abolition movement?

- How do you think that Wendell’s social status impacted the way he viewed the world?

- According to Justice Holmes, how did the majority opinion in Lochner v. New York violate judicial restraint?

- Why do you think The Common Law is considered to be so revolutionary?

Sources

Special thanks to author and historian Stephen Budiansky for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured image: Portrait of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927)

Budiansky, Stephen. Oliver Wendell Holmes: A Life in War, Law, and Ideas. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Cushman, Clare, ed. “Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr: 1902-1932.” The Supreme Court Justices of the United States: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2013.

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925)

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905)

“Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.: Chief Justice memorial,” Mass.gov, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/person/oliver-wendell-holmes-jr.

“Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., 1902-1932.” Supreme Court Historical Society. https://supremecourthistory.org/associate-justices/oliver-wendell-holmes-jr-1902-1932/.

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

Shriver, Henry C. “Oliver Wendell Holmes: Lawyer.” American Bar Association Journal 24, no. 2 (1938). 157-162. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25713567?seq=1.

Wells, Catherine Pierce. “Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and the American Civil War.” Journal of Supreme Court History 40, no. 3 (2015). 282-313.

G. Edward White, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 3.