Thurgood Marshall as an Advocate

Before he was a Supreme Court Justice, Marshall advocated for civil rights as a lawyer with the NAACP.

Background

Thurgood Marshall, born in Baltimore, Maryland, was the first Black Justice of the Supreme Court. Before President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him to the bench in 1967, Marshall had a successful career as a civil rights lawyer. He aspired to study law at his state school, the University of Maryland, but the school was segregated and refused to admit him. He earned his law degree from Howard University in Washington, D.C., a college created for Black students during Reconstruction.

After graduation, Marshall opened a small law practice in Baltimore. The Great Depression hit the city hard, so Marshall accepted many cases at little to no cost to his clients. He was also deeply involved with the local NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). It was this work that shaped his career and led to his Supreme Court nomination.

The majority of Marshall’s advocacy with the NAACP challenged local practices that were inconsistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. By the time he became an Associate Justice, he had argued nearly 30 civil rights cases before the Supreme Court. Marshall’s advocacy was characterized by his work strategizing with the NAACP to challenge local segregation laws, his victories in desegregating education, and his strong presence in the courtroom.

Marshall and the NAACP

Marshall and the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund attacked private housing covenants and local laws to inspire change on the federal level. The team believed that law was “social engineering,” and that they could use it to build an ideal society. Marshall and the NAACP decided which cases “would prove the best vehicles to advance certain legal principles and then hope to find plaintiffs who could assert appropriate claims.” Marshall risked his life traversing the South to hear these cases. Most hotels and restaurants refused to accommodate African Americans, so he stayed with locals, sometimes moving houses every night to keep hidden from angry white Southerners who knew he was in town to hear a case. Armed Black citizens sat outside the homes at night to protect him. He constantly feared violence, especially after local police in Texas and Tennessee directly threatened him.

The risks Marshall and his NAACP colleagues took to try these cases were not in vain. Their efforts led to several notable civil rights victories in voting, public spaces, and housing.

Voting Rights

After Reconstruction, Southern states used a variety of methods to disenfranchise Black voters, like literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses. Another method, white primaries, excluded Black voters in primary elections. The NAACP knew that it was important to challenge these laws in court: If Black citizens could not vote, then discriminatory laws would be more difficult to change. Marshall successfully argued that white primaries violated equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment in Smith v. Allwright (1944). The Court struck down the law.

Desegregating Public Spaces

The Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) legalized segregation and led to Jim Crow laws. States, mostly in the South, created laws requiring “separate but equal” public facilities for white and Black people. The designated Black facilities were always in worse condition than their white counterparts. As an advocate with the NAACP, Marshall successfully challenged some of these local segregation mandates. For example, Holmes v. Atlanta (1955) resulted in desegregation of public recreation facilities after an all-white public golf course denied entry to the Holmes family because of their race. What started as a local case about equal access to golf courses in one city became a Supreme Court ruling establishing that discrimination in public recreation facilities everywhere was unconstitutional. Similarly, the plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle (1956) asserted that Montgomery, Alabama’s segregated busing system violated the Constitution. The NAACP identified this case as one that could have a significant impact on the nation and appealed it directly to the Supreme Court, which ruled that segregation in public transportation was unconstitutional.

Housing Covenants

Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) also demonstrated how Marshall and the NAACP targeted local law to enact federal change. The case questioned the constitutionality of racially restrictive housing covenants used by new suburban neighborhoods throughout the country to remain whites-only. In bringing this case, which originated in a St. Louis neighborhood, to the Supreme Court, Marshall aimed not only to eliminate racist language in private housing covenants, but also to keep federal agencies from engaging in racist practices. The Court unanimously held that enforcement of private housing covenants was unconstitutional, though the covenants themselves were legal until the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Education

Early Challenges to Segregated Schools

One of Marshall’s most well-known accomplishments was successfully arguing for the abolishment of the “separate but equal” doctrine of school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), but several lesser known cases led to the successful challenge to school segregation in Brown. In 1935, Marshall unsuccessfully challenged schooling practices in Baltimore County, Maryland, just outside of where he grew up. The district had no public African-American high schools. Black students had to apply, be admitted, and pay a non-resident tuition fee to attend school in another district. The state court ruled in favor of Baltimore County, holding that the entrance exam required for Black students for the other district was the equivalent of the final exams that white students took.

After the loss in Baltimore County, Marshall and the NAACP adjusted their strategy. Over the next two decades, they challenged segregation in higher education and teacher salaries. They started with the University of Maryland, Marshall’s own state school. He recalled that “my first idea was to get even with Maryland for not letting me go to its law school.” In Murray v. Pearson (1936), the state court ruled in Marshall’s favor. It held that having no public law school for Black students was unconstitutional. At the same time, Marshall began challenging teacher salaries. After persuading some local Maryland school boards to agree to equalize pay for their Black educators, he traveled across the South to continue the mission. This work earned him the role of head of legal activities for the NAACP. Then, in the late 1940s, several higher education cases made it to the Supreme Court. For instance, in another case he argued, Sweatt v. Painter (1950), the Court ruled that the University of Texas Law School violated the Fourteenth Amendment by refusing to admit Black student Herman Marion Sweatt. Marshall served as an advocate in similar cases, tackling racially restrictive admissions policies at universities in Alabama, Oklahoma, and Florida

.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Until this point, the education cases focused on unequal facilities. For example, the University of Oklahoma rejected Ada Lois Sipuel because the school did not have separate facilities for Black students, and the law mandated segregation. The Court held in Sipuel v. Board of Regents (1948) that the state must provide Sipuel an education equal to her peers. The state complied by establishing a Black law school in a roped-off section of the state capital. Sipuel refused to attend. Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) provided an opportunity to directly challenge the constitutionality of segregation. Marshall argued that separate education was inherently unequal, and therefore unconstitutional. The Court unanimously ruled that segregated schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection.

Marshall in the Courtroom

As a litigator, Marshall was a skilled storyteller who emphasized the humanity of his clients. He brought their stories to life, demonstrating the impact of the law to the people who had the ability to change it. This was especially significant in criminal cases. His defense could literally mean the difference between life and death. Marshall went to great lengths to protect the rights of his defendants, often calling upon his experience and political connections. In one instance, Marshall used NAACP connections to ask the governor of Florida to change a death sentence to life imprisonment. In the Jim Crow era, Marshall and the NAACP learned, it was difficult to prove innocence for a wrongly accused Black man, but they could save his life.

Additionally, Marshall relied on studies about the psychological impact of discrimination to support his cases. For example, in Shelley, he argued that racially restrictive covenants led to overcrowding, which was correlated with crime and higher infant mortality rates. Similarly, in Brown, rather than focusing on the physical differences between white and Black schools, Marshall highlighted how the inferiority that Black children experienced as a result of those conditions adversely impacted them throughout their lives. The language of this argument was reprised in the Supreme Court’s opinion in Brown.

Finally, Marshall’s position as a high-profile Black attorney challenged white attitudes and empowered African Americans. His strong courtroom presence both helped his arguments and influenced the community. As he presented his cases, “he was angry and directed his anger as a weapon against bigotry, intolerance, and hatred.” Marshall recalled a particularly intense cross-examination he conducted in Lyons v. Oklahoma (1941), where he questioned white police officers:

They all became angry at the idea of a Negro pushing them into tight corners and making their lies so obvious. Boy, did I like that—and did the Negroes in the courtroom like it. You can’t imagine what it means to those people down there to know that there is an organization that will help them.

Marshall’s outstanding record and achievements earned him appointments to a federal judgeship on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, to the position of Solicitor General, and, finally, to the Supreme Court, where he served as an Associate Justice for 25 years.

Discussion Questions

- How does Thurgood Marshall’s time as a lawyer reflect the development of the Civil Rights Movement from 1945-1960?

- How did Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP challenge Jim Crow laws?

- How has the Fourteenth Amendment supported and motivated the Civil Rights Movement?

- What challenges did Thurgood Marshall face in achieving his goals?

- Which one of Thurgood Marshall’s cases do you think was the most important? Why?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Kenneth Mack for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Crew, Spencer R. Thurgood Marshall: A Life in American History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, 2019.

Cushman, Clare. “Thurgood Marshall: 1967-1991.” The Supreme Court Justices of the United States: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-2012. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2013.

Garrett, Elizabeth Garrett. “Review of Mark V. Tushnet, Making Civil Rights Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1936-1961 and Making Constitutional Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1961-1991.” Journal of Supreme Court History (2016), no 2.

Sullivan, Patricia. Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: The New Press, 2009.

Tushnet, Mark V. Making Civil Rights Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1936-1961. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

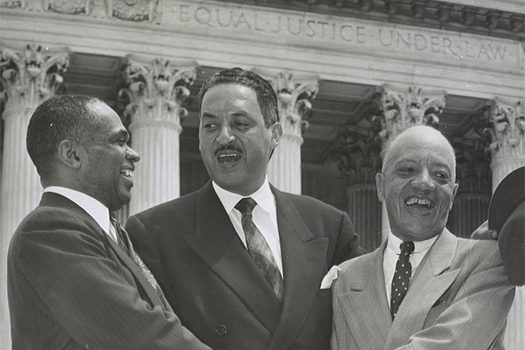

Featured image: Harold P. Boulware, Thurgood Marshall, and Spottswood W. Robinson III confer at the Supreme Court prior to presenting arguments against segregation in schools during Brown v. Board of Education case., 1953. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/99472832/.