The Roles of Wives: 1953-1969

How wives of justices supported their husbands, pursued their own interests, and managed their households and families

The role of Supreme Court wives changed during the 1950s and 1960s. Before the Great Depression, the wives of justices carried significant social responsibility. Their calendars were filled with dinners, functions, and visits with the wives of cabinet members and Congressmen. By the 1950s, they had fewer social obligations. Costly events like regular afternoon teas were abandoned during the Depression and World War II. There was also a new emphasis on ethics following President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1937 proposal to expand the court—potentially with the intent of nominating justices who would support his legislation. Justices were now expected to distance themselves from the other branches of government to ensure that they were impartial. Dorothy Kurgans Goldberg, the wife of Justice Arthur Goldberg, stated that “justices and their wives are not expected to reciprocate invitations extended to them by others, nor do they very often accept invitations other than from their private friends.”

The wives’ duties were much more intimate than the frequent and lavish hosting that was expected in the late 19th century. For example, many wives offered hospitality to each year’s new crop of law clerks, hosting them in their homes and organizing sightseeing trips in the nation’s capital during their year-long clerkship. Additionally, wives provided an important support system. As the first Black justice nominated to the Court, Thurgood Marshall faced extreme scrutiny and racism. His wife, Cecilia “Cissy” Marshall, supported him with her presence while he gave testimony during his confirmation hearings. There was also a societal expectation for wives to be present in the Court’s family pews when their husbands delivered opinions. During this era, the wives organized occasional potluck lunches at the Court, to share recipes, stories about their families, and generally support each other—a tradition that continues today.

Relieved of demanding social obligations, Supreme Court wives in the 1950s and 1960s pursued their own interests and careers. Many engaged in charitable work, like Nina Warren, wife of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who supported the Salvation Army. Dorothy Goldberg was an artist and an activist. She founded several community programs that promoted the arts, helped people find jobs, and prevented juvenile delinquency. Later, she became a human rights activist, serving as a U.S. delegate at multiple international conferences. Carolyn Agger Fortas, wife of Abe Fortas, held several government positions before becoming a successful tax lawyer during a time when few women went into law. Cissy Marshall met Justice Thurgood Marshall working for the Legal Defense Fund on Brown v. Board of Education (1954), though she stopped working after they married in 1955.

These women all made major life changes so their spouses could serve on the Supreme Court. Often, a Supreme Court justiceship required that the family relocate to Washington, D.C. For Nina Warren, for example, this meant a cross-country move from California with six children. For Marjorie Brennan, it meant moving further from her hometown. She shared with a reporter that she was “a little scared” about the move to D.C. from New Jersey, where she grew up and where her husband William J. Brennan was serving as a judge.

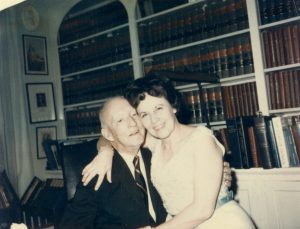

Accepting a judgeship also affected families’ finances. Even at the Supreme Court level, it sometimes meant a major pay cut, putting financial strain on the family. The salary of a justice ($35,000 as of 1955) was significantly less than what a lawyer could earn in private practice. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated successful attorney Abe Fortas to the Court. Fortas’ wife, Carolyn, was hesitant for him to give up his lucrative private practice. To try to convince her, Justice Hugo L. Black and his wife Elizabeth hosted a dinner party where they shared their positive experiences with the Court. According to Elizabeth’s diary, Carolyn worried that “they can’t live on the small Court salary and may have to give up their new home.” Though Fortas did accept the nomination, President Johnson, who was a close friend, recalled that Carolyn stopped speaking to him for months.

On the other hand, families already in government service may have received a raise. Before his nomination to the Supreme Court, Justice Byron White earned $21,000 per year as Deputy Attorney General. The promotion allowed the family to upgrade from their apartment in Washington D.C. to a new-construction home in suburban McLean, Virginia on almost an acre of land. Marion shared in an interview about the home that the children especially loved playing in the woods behind their yard, which were “full of snakes and poison ivy, but they love[d] it, and it’s really marvelous for them.”

Though no woman would serve on the Supreme Court bench until Sandra Day O’Connor in 1981, the wives of justices played important roles behind the scenes. Many uprooted their lives to move to D.C., provided support for their husbands, managed their households and families, and were important members of their own work and volunteer communities.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think it is important for Supreme Court justices to be impartial?

- Why do you think Marjorie Brennan was “a little scared” about moving to Washington D.C.?

- How did joining the Supreme Court affect the justices’ families?

Extension Activity

Read the resource The Role of Supreme Court Wives (1801-1835). How has the role of Supreme Court wives changed over time?

Sources

Special thanks to the Supreme Court Historical Society’s Director of Publications Clare Cushman for her review, feedback, and additional information.

“Carolyn Agger.” Yale Law Women+. https://ylw.yale.edu/portraits-project/carolyn-agger-ll-b-1938/.

Culver, Virginia. “Justice’s wife was a community servant.” The Denver Post. May 7, 2016. https://www.denverpost.com/2009/01/22/justices-wife-was-a-community-servant/.

Cushman, Clare. “Cecilia Marshall: An Appreciation.” Supreme Court Historical Society. https://supremecourthistory.org/society-news/cecilia-marshall-an-appreciation/.

Cushman, Clare. “Wives, Children…Husbands: Supporting Roles”, Journal of Supreme Court History, vol. 36, no. 3 (2011).

Hutchinson, Dennis. The Man Who Once was Whizzer White: A Portrait of Justice Byron R. White.

“Judicial Salaries: Supreme Court Justices.” Federal Judicial Center.

https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/judicial-salaries-supreme-court-justices.

Stern, Seth and Stephen Wermiel. Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2010.

“LDF Tribute to Cecilia Marshall: 1928–2022.” Legal Defense Fund. https://www.naacpldf.org/press-release/cecilia-marshall-tribute/

All photographs are courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.