The Cherokee Nation Cases (1831-1832)

Significant Case

The lawsuits that forced the examination of the relationship between law and politics, particularly with respect to the Supreme Court’s ability to enforce its judgment during the early years of the Republic.

Background

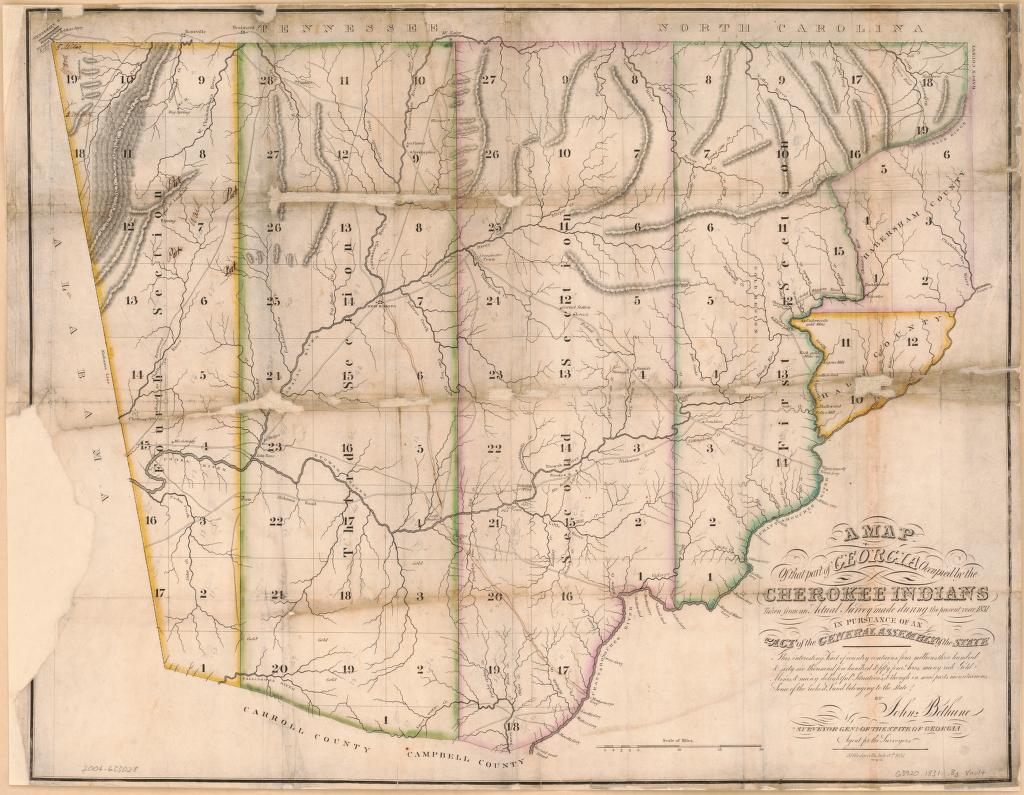

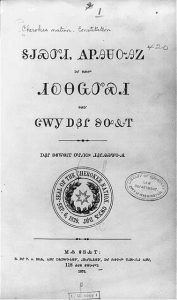

The struggle for land between the American settlers and the original Native American inhabitants began when the first Europeans arrived in North America in the early 1500s. Over the centuries, the settlers and the native people engaged in a series of treaties which, at times, were later disregarded by the Europeans and Americans. As small, rustic settlements developed into the British colonies, the Native Nations were pushed out of their territory often resulting in conflict and violence. When the American colonies decided to declare themselves independent from Great Britain in 1776, several of the Native Nations, including the Cherokee, supported the British. They later signed a peace treaty, however, with the new American states and eventually the new federal government. In the various treaties, such as the Treaty of Hopewell and the Treaty of Holston River, the United States promised it would protect Cherokee land and guarantee the Tribe’s territorial boundaries. For the next few decades, the United States kept its commitment, and the Cherokee lived peacefully in Georgia and Arkansas. Many pursued an agricultural way of life, building homes and farms and some even acquired enslaved people. They built a capital city called New Echota and Sequoyah, an important Cherokee representative, developed a written version of the Cherokee language, one of the first of any Native Nation. Under their Chief John Ross, the Cherokees adopted their own constitution and lived peacefully.

Over time, Georgia made it clear they wanted the Native American land within their state borders to become Georgian land and they would take the land by force if necessary. When the Native Nations refused to sell their land and move, Georgia began to pass laws challenging Native sovereignty and the authority of the U.S. government. The Creek Nation was the first to lose their land after Georgia forced them into a treaty that did not benefit the Tribe. Though the U.S. government supported the Creek people, Georgia ignored federal authority and forced them west in 1828 through a series of Removal Acts. Andrew Jackson’s election in 1828 accelerated (sped up) the conflict; Jackson had already helped drive natives from their land during his time in the army and was a supporter of the Indian Removal Bill, which he signed into law in 1830. Under his leadership, many Native Nations were forcibly removed and sent further west. When gold was discovered on Cherokee land a few months later, the Georgia legislature passed more legislation encroaching on Cherokee land and forbidding them to dig for gold in their own territory. Frustrated, the Cherokee refused to negotiate with Georgia and hired one of the greatest constitutional lawyers of the time, former U.S. Attorney General, William Wirt.

Case 1: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831)

In 1791, the United States entered the Treaty of Peace and Friendship with the Cherokee Nation. Within that treaty, the U.S. government promised to respect the territorial integrity of the Cherokee lands. The Constitution made treaties the “Supreme Law of the Land.” Additionally, the Supreme Court ruled in Fletcher v. Peck that it would strike down state laws that violate the Constitution. With the law and precedent on his side, William Wirt was left with jurisdictional concerns – how to get the Cherokees’ case to the high court. Filing a case in lower federal courts could likely involve President Jackson or his cabinet. He had legal standing for a “trespass” case, but Georgia state courts would likely prove unsympathetic to his claim. Article III of the Constitution states that the, “Supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction” in all cases “in which a state shall be Party.” His best option, Wirt believed, would be to sue the state of Georgia directly so that the Supreme Court would hear the case.

In 1831, Mr. Wirt filed a lawsuit, on behalf of the Cherokee Nation, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, in the Supreme Court of the United States. The goal was to obtain an injunction stopping Georgia and its officers from enforcing Georgia laws within Cherokee territory which challenged their sovereignty. The Cherokee Nation considered itself to be a separate and distinct state capable of self-government and not part of the United States. Georgia did not respond to the case or send anyone to represent them in court.

Issue

Could the Cherokee Nation sue Georgia in federal court under the Court’s Article III original jurisdiction to stop Georgia from enforcing their state laws within Cherokee territory?

Summary

No. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote on behalf of a divided Court that the Supreme Court lacked original jurisdiction over the case. While Georgia was indeed a state, the Cherokee Nation was not a state of the union or a foreign state; rather its “relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to its guardian.” In other words, the Indian tribes (Native Nations) were considered “domestic dependent nations.” Thus, the Cherokee did not have the right to sue Georgia in the U.S. court system. The Court’s decision was narrow, however, and did not mention that the Cherokees had argued that their case arose under a treaty. Chief Justice Marshall also delivered an extra-judicial opinion and suggested that the question of territorial rights could be decided by the Supreme Court in a “proper case with proper parties.” The Cherokee Nation and Mr. Wirt would not have to wait long for such a case to arise.

Case 2: Worcester v. Georgia (1832)

Georgia continued to pass legislation that attacked the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. One law required, “all white persons residing within the limits of the Cherokee nation” to have a license from the governor and to swear an oath to support Georgia’s laws. When a group of eleven missionaries refused to take the oath because it would damage their relationship with the Cherokee people, they were arrested. The missionaries were quickly convicted in a Georgia state court and sentenced to several years of hard labor in prison. Georgia’s governor offered to pardon the missionaries if they would take the oath, but S.A. Worcester and his colleague Jeremiah Evarts still refused. They believed their refusal would help the cause of the Cherokees. Mr. Wirt took their case.

Mr. Wirt appealed the missionaries’ case to the Supreme Court and the justices heard arguments in February of 1832. Once again, Georgia did not appear. The Governor even stated that he would, “disregard all unconstitutional requisitions” and would “resist Federal usurpations.” Similarly, the Georgia legislature threatened to ignore any attempt by the Supreme Court to reverse its state court’s decision and would consider any interference as arbitrary and unconstitutional.

Issue

Did the state of Georgia have the authority to regulate intercourse (trade) between citizens of its state and members of the Cherokee Nation or to apply Georgia law within the bounds of sovereign Cherokee Nation territory?

Summary

No. This time Chief Justice Marshall delivered a 5-1 decision holding unconstitutional the Georgia law, under which Worcester and his fellow missionaries were prosecuted, unconstitutional. In his opinion, Marshall noted that the treaties and laws of the United States regard Indian territory as separate and that interactions with them should be carried out by the federal government. Chief Justice Marshall reasoned, “The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States.” Georgia had interfered with the authority of both the federal government and the Cherokee Nation and lost.

Precedent Set

After the second decision came down in the Cherokees’ favor, the Supreme Court recognized the status and power of the Cherokee Nation by upholding protections to the tribe. Marshall’s decision established that Native Nations, including the Cherokee, were protected by federal law and had the right to govern their own people and their own land. States felt that the decisions violated their autonomy as they could no longer pass laws affecting Natives living within their borders, and that the federal government and Native nations were gaining too much power.

Additional Context

“Well, John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

—President Andrew Jackson (rumored)

Despite these Supreme Court rulings, President Andrew Jackson made it clear he would not recognize Native people’s rights. Along with the state of Georgia, Jackson ignored the Court’s decision (which carries the same weight as a federal law does), provoking a constitutional standoff within the federal government by refusing to enforce the ruling.

Jackson soon faced a similar challenge of his federal authority when South Carolina enacted the Ordinance of Nullification, which would have declared that a federal tariff did not apply within its state borders. This time, Jackson sided with the federal government: “I consider…the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the…Constitution.” This included Supreme Court decisions, or the authority of the entire federal government would be threatened.

By 1838 the Cherokee had been forced off their land within the state of Georgia and pushed west towards the Mississippi River. By 1850, 60,000 Native Americans from five tribes— Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw —were removed from their ancestral lands. This forcible relocation known as the Trail of Tears led to disease, starvation, and thousands of deaths for Native peoples. There were forced removals from other areas of the United States as well, with Native Tribes such as the Potawatomi being marched on the Trail of Death. The Native Nations were promised reservation lands to protect their autonomy and keep them separate from the non-Native settlers. Those reservations would later be broken up and sold by the federal government through the Allotment Acts in the 1880s. Despite these extreme circumstances, many tribes are still functioning and governing. For example, there are 39 federally recognized tribes in Oklahoma alone and they are the largest economic driver in the state. The Cherokee and Navajo Nations have the most tribal members of any tribe in the United States and are still working to protect their inherent sovereignty and preserve their respective culture, language, and values.

Discussion Questions

- How did the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia decision influence the development of Worcester v. Georgia? Why did the Supreme Court have jurisdiction in the second case?

- How did the decision of Worcester v. Georgia impact the relationship between states and Native Tribes?

- How does the decision in Worcester v. Georgia illustrate the importance of checks and balances by giving the federal government exclusive rights over Indian affairs?

- Ultimately, which level of government gained more power from the Court’s rulings in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia?

Sources

Special thanks to internationally renowned indigenous rights scholar and Chief Justice of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation of Oklahoma, Law Professor Angela R. Riley for her review, feedback, and additional information.

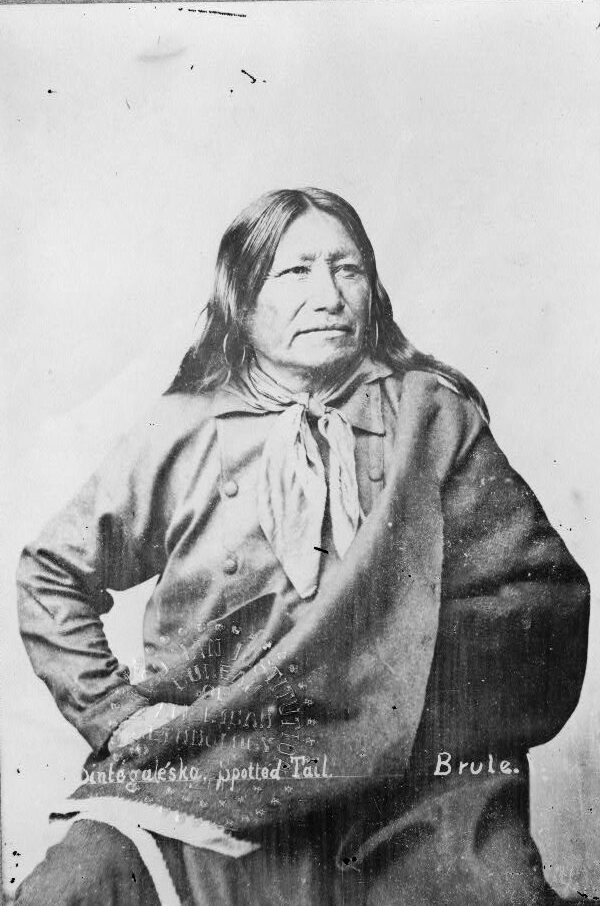

Feature Image: John Ross, a Cherokee chief / drawn, printed & coloured at the Lithographic & Print Colouring Establishment, 94 Walnut St. (1834). Library of Congress.

Stephen Breyer, “The Cherokee Indians and the Supreme Court.” Journal of the Supreme Court Vol. 25-3 (2000).215-227.