New York Times Company v. Sullivan (1964)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that arose during the Civil Rights Movement and protected freedom of the press

Background

During the 1960s, African-American activists across the United States fought for civil rights. Although the Supreme Court overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), many Southern states avoided desegregating schools and public facilities, and de facto segregation persisted in the North. Across the nation, activists used direct-action tactics like boycotts and sit-ins to fight for change. Local white segregationists and police clashed with these activists, sometimes violently.

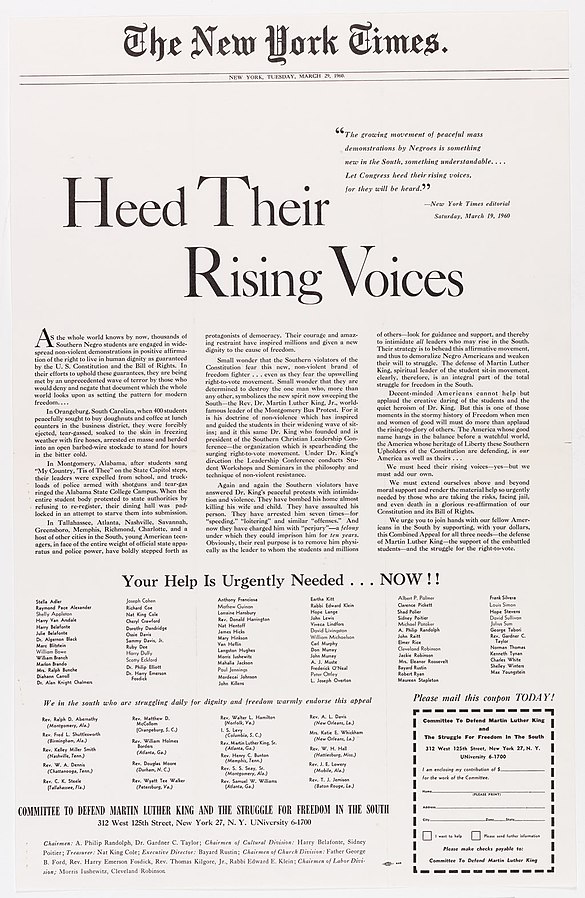

One of these activists was Martin Luther King Jr. The press gave him significant favorable coverage, and his praise for the growing sit-in movement influenced many people. In early 1960, Georgia law enforcement used an Alabama warrant to arrest King for tax fraud. There was no evidence to prove he violated the law. To cover his legal fees, a group of allies purchased a full-page advertisement in the New York Times asking for donations. The ad, titled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” ran on March 29, 1960. It described actions taken against student protesters and attacks on King.

The ad contained several unintentional errors, including false descriptions of police actions in Alabama against a student sit-in. The Times sold few papers in Alabama—394 of the 650,000 daily copies—but a local paper published a high-profile editorial complaining that the ad contained lies. A copy of the paper made its way to the desk of the mayor of the city of Montgomery (the Alabama state capitol), who shared it with the commissioner of public affairs, L.B. Sullivan.

Facts

The ad did not mention any official by name, but Sullivan believed descriptions of the Montgomery police referred to him. Specifically, he focused on a passage that referred to the police padlocking an on-campus dining hall to starve student protestors out, which never actually happened. He claimed that the references to the police, especially in the context of incorrect information, negatively reflected on him and would damage his reputation. Sullivan filed a libel suit against the Times.

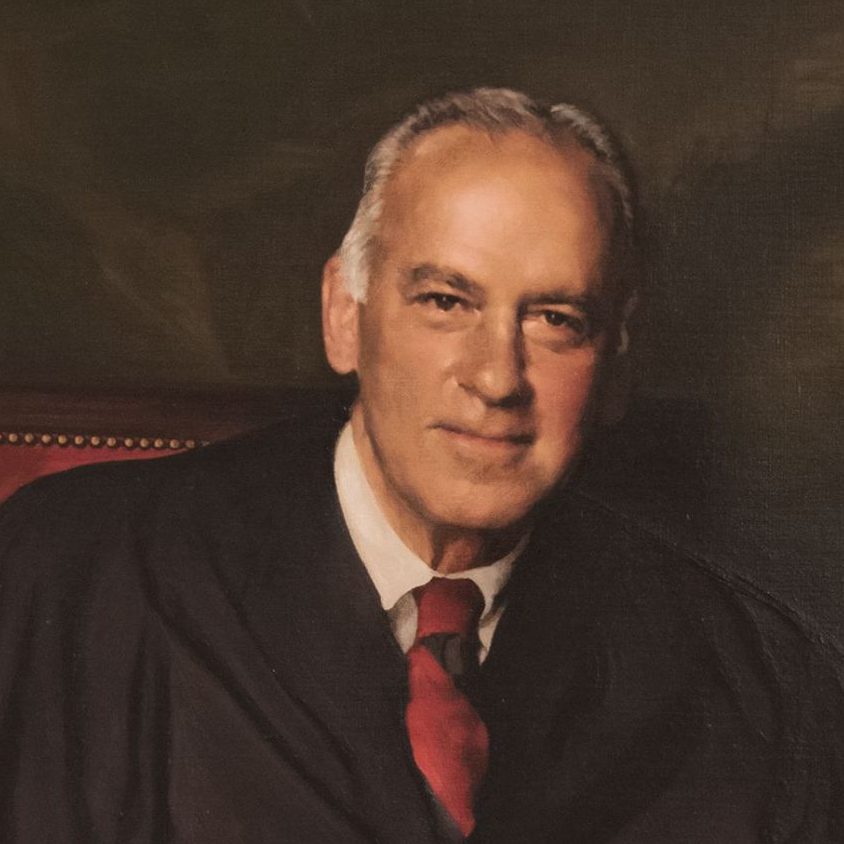

Judge Walter Burgwyn Jones first heard the case on November 1, 1960. The day before the trial, he attended the town’s Civil War festival and reenacted the swearing-in of Jefferson Davis as president of the Confederacy. At the trial, some spectators wore Confederate uniforms and carried pistols from the ongoing Civil War celebrations. These celebrations were not uncommon in Montgomery at the time, especially with the approach of the Civil War’s 100th anniversary in 1961. An all-white, male jury judged the case.

Alabama, and many other states at the time, had strict libel laws before the decision in Sullivan. A plaintiff could receive “general damages”—win a libel lawsuit —without having to show that an individual’s speech had actually harmed them (damaged their reputation). If a jury simply found that someone’s speech was about “and concerning” someone (which was exceptionally easy to prove), then the law presumed that the words were false and malicious.

A jury in state court ruled in favor of Sullivan and ordered the Times to pay $500,000 in damages (about $5.2 million in 2024)—had it not eventually won the case, this amount might have been enough to close the newspaper down. The Alabama State Supreme Court affirmed the jury’s decision on August 30, 1962, and the Times appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Issues

Does the First Amendment protect statements that unintentionally contain false information?

Does Alabama’s libel law violate the First Amendment’s protections of free press and free speech?

Summary

The Court held that Alabama’s libel law violated the First Amendment. In his unanimous opinion, Justice William J. Brennan wrote that “actual malice” is required for libel. This means that there was knowledge of falsehood and intent to use it for harm. The Court decided there was no evidence of actual malice from the Times. The opinion also stated that the advertisement addressed a major public issue of the time, and therefore was the kind of speech protected by the First Amendment. Issuing unlimited fines as a punishment for unintentional inaccuracies, the opinion noted, restricts free speech and press. According to Justice Brennan, “under such a rule, would-be critics may be deterred from voicing their criticism” of public officials because they are afraid of being fined. Finally, the Court reasoned there was insufficient evidence to prove that the allegedly libelous statements in the ad were about Sullivan.

Precedent Set

Sullivan revolutionized the Court’s interpretation of the First Amendment and was an important win for the Times and the press overall. The case acknowledged that criticism of government and public officials is a protected aspect of free speech and a natural consequence of the “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” debate that comes with democracy. Because of Sullivan, news outlets can report freely about public officials without fear of being sued for damages. The “actual malice” rule is the standard for libel judgments, shielding the press from lawsuits for unintentional factual errors that are an unavoidable reality of publishing.

Additional Context

The impact of Sullivan was at that time as important to the Civil Rights Movement as it was to freedom of the press. At the time, white segregationists engaged in massive resistance to protest desegregation efforts like the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Brown v. Board of Education decision. They used a variety of methods to oppose integration, including public school closures, white primaries, and Citizens’ Councils. Libel attacks became a massive resistance strategy. Newspapers played a pivotal role in educating the country about civil rights, so segregationists used lawsuits to silence pro-integration media. Shortly after Sullivan sued for the “Heed Their Rising Voices” ad, subsequent articles about the city of Birmingham—“Fear and Hatred Grip Birmingham” and “Race Issues Shake Alabama Structure”—prompted a slew of hate mail and four more libel suits against the Times. As a result, the paper banned its reporters from the state for the next two and a half years. Sullivan “permitted the press to report fully and freely on the civil rights movement.” This coverage played an important role in educating the public and contributed to the passing of legislation, notably the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Decision

The Court issued a unanimous decision in favor of New York Times Company.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

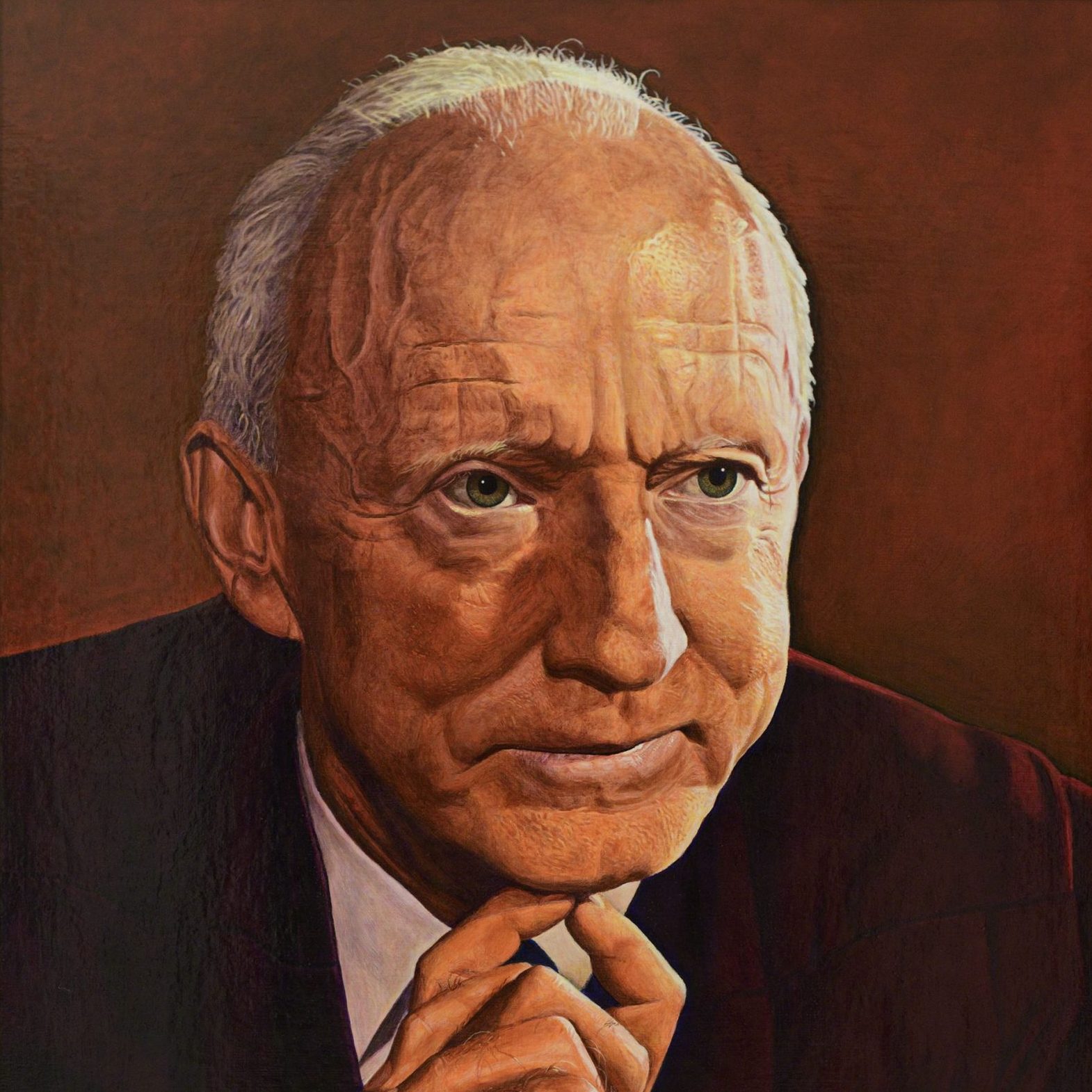

Warren

-

Black

-

Douglas

-

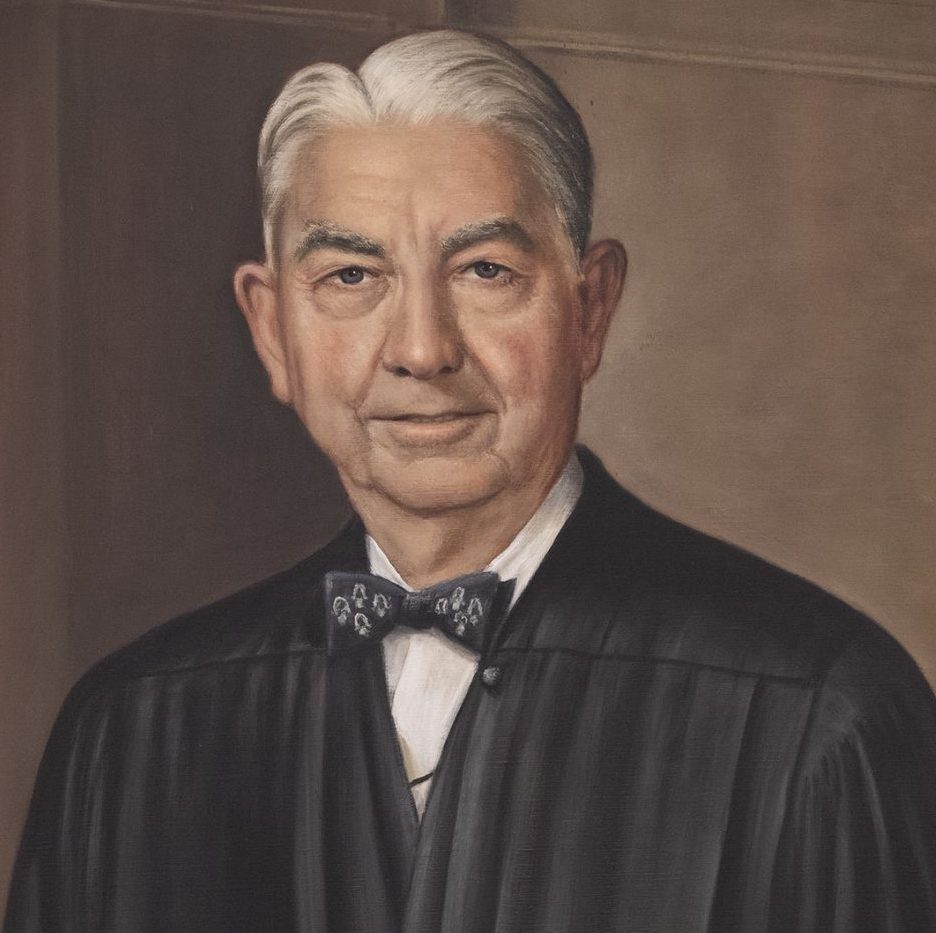

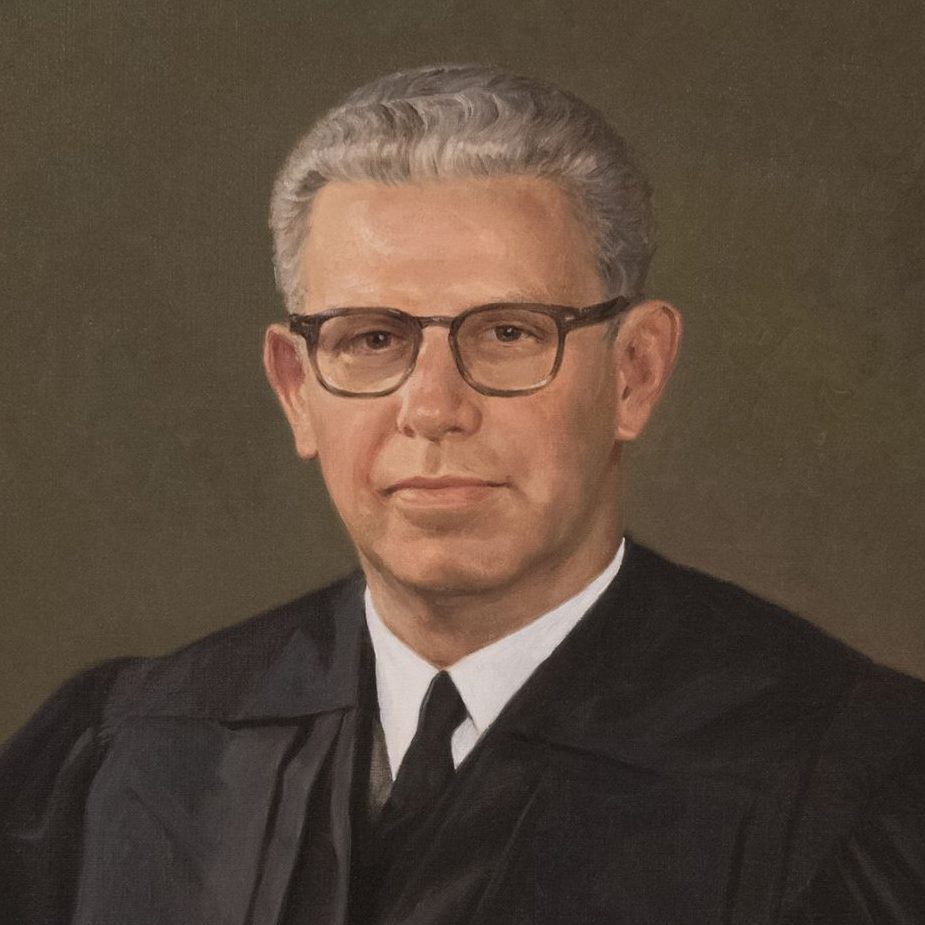

Clark

-

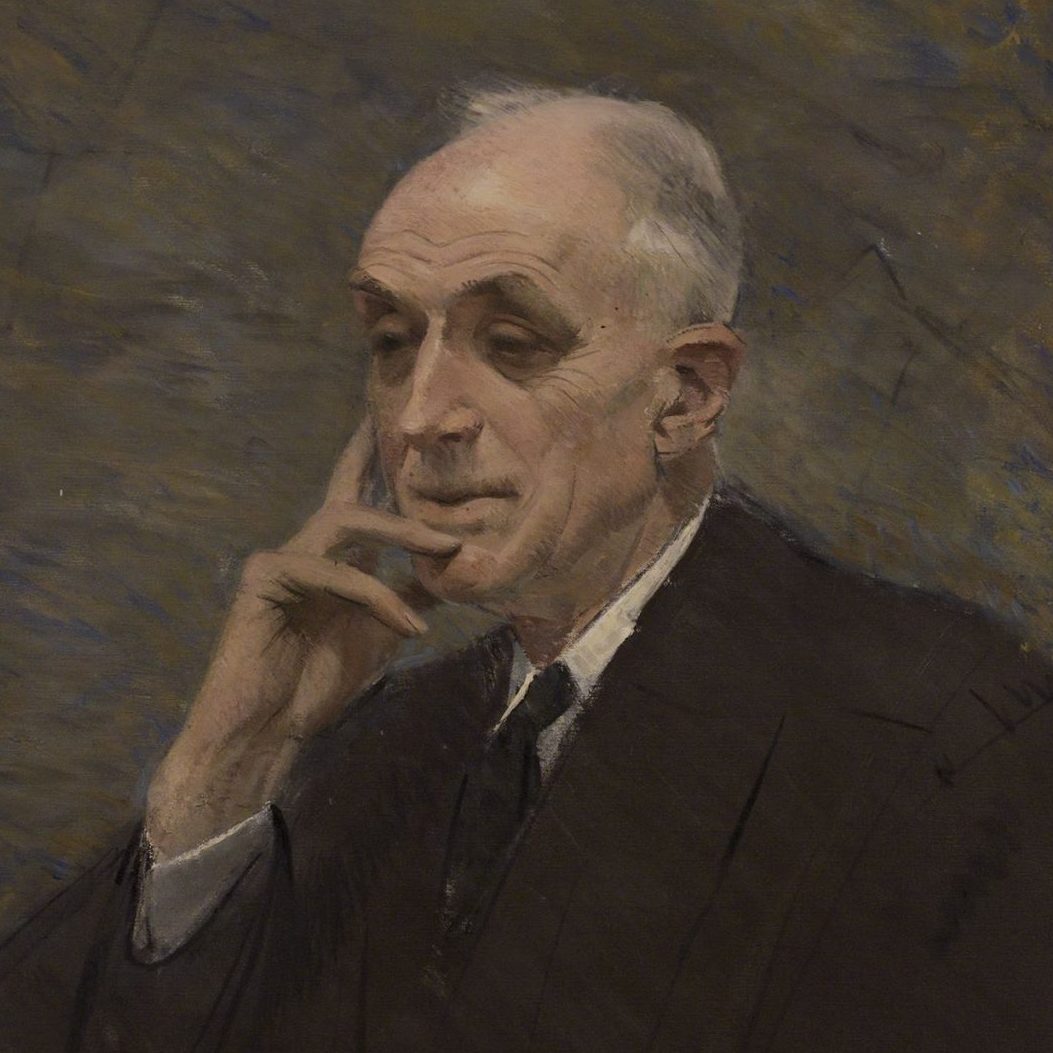

Harlan II

-

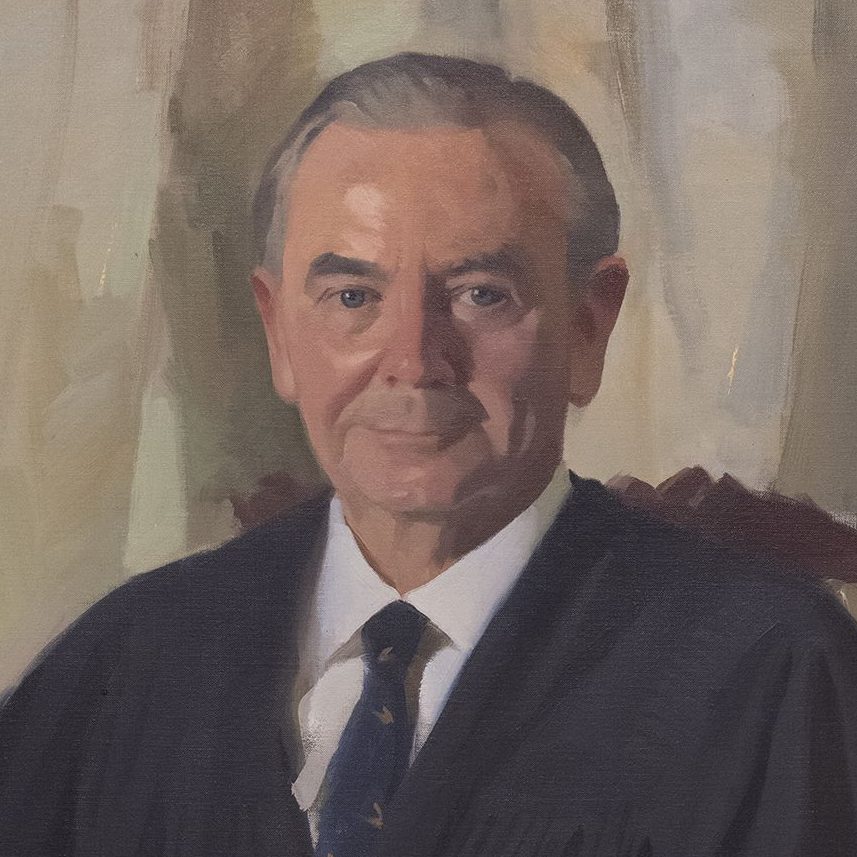

Brennan

-

Stewart

-

White

-

Goldberg

-

Majority Opinion

William J. Brennan Jr.Read More Close“A state cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, award damages to a public official for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves ‘actual malice’ — that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false.”

-

Concurring Opinion

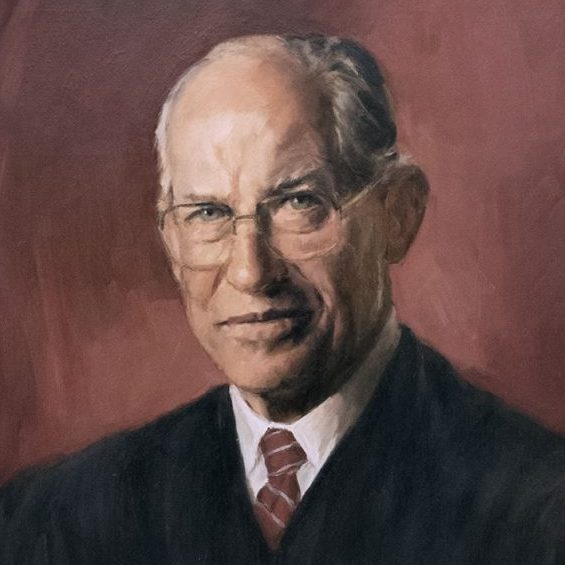

Hugo L. BlackRead More Close“Malice,’ even as defined by the Court, is an elusive, abstract concept, hard to prove and hard to disprove…Unlike the Court, therefore, I vote to reverse exclusively on the ground that the Times and the individual defendants had an absolute, unconditional constitutional right to publish in the Times advertisement their criticisms of the Montgomery agencies and officials.”

Discussion Questions

- How did civil rights activists and political leaders challenge segregation during the 1950s and 1960s?

- Why was Martin Luther King Jr. arrested for tax fraud if there was no evidence?

- How did the Sullivan case impact the Civil Rights Movement?

- How did the Sullivan case protect freedom of the press?

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan has been described as “arguably the most important First Amendment case in history.” Why is Sullivan so important for free press?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar Helen Knowles-Gardener for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Barbas, Samantha. Actual Malice: Civil Rights and Freedom of the Press in New York Times v. Sullivan. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2023.

Brown, Stephen P. Alabama Justice: The Cases that Changed a Nation. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2020.

Goodale, James C. Is the Public ‘Getting Even’ with Press in Libel Cases? N.Y.L.J., Aug. 11, 1982.

Knowles, Helen J and Steven B. Lichtman. “Introduction: Oh What a Tangled Web They Weave.” Judging Free Speech: First Amendment Jurisprudence of US Supreme Court Justices. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Powe Jr., Lucas A. The Warren Court and American Politics. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000.

Featured image: New York Times Advertisement; 3/29/1960; Records of District Courts of the United States, DocsTeach, National Archives Catalog. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/new-york-times-advertisement.