Lochner v. New York (1905)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court’s decision that struck down state limits on work hours in bakeries.

Background

During the late 19th century, cities in the United States became centers of industrial growth. People moved from rural areas and emigrated from countries around the world to take advantage of economic opportunities created by factories and mass production. As the number of women working outside the home increased, more families were in need of prepared food items, like bread. Additionally, most of the urban population lived in overcrowded tenements that often did not have ovens. As a result, the bread baking industry expanded.

Like most other urban establishments, bread bakeries were unsanitary. Because ovens were so heavy—and rent was so cheap—most bread bakeries operated in tenement cellars. The cellars had saturated dirt or wooden floors, low ceilings, and little ventilation. The sewer, which frequently leaked, was also located in the cellar. Constant exposure to flour dust, fumes, and extreme temperatures led to health setbacks.

The work itself was challenging. Bakers measured and dumped ingredients using heavy shovels and sacks, not the cups and teaspoons known to modern bakers. Hours were so long that most contracts required bakers to sleep in the shop—usually on the boards they used to knead bread. A typical baker worked 74 hours every week, but some were reported to work as many as 114 hours.

New York state’s baking industry came under scrutiny when the New York Press published a muckraking report titled “Bread and Filth Cooked Together” in September 1894. The article, which detailed “vermin and dirt abound” and “a grind that makes ambition for personal cleanliness impossible” drew the attention of reformers, organized labor, and politicians. Unsafe working conditions were not unique to the baking industry, but the momentum generated by this exposé led the New York State Legislature to unanimously pass the Bakeshop Act in the spring of 1895. The act implemented standards for sanitation and working conditions in bakeries. It also limited working hours for bakers to a maximum of 10 hours per day or 60 hours per week.

Facts

Joseph Lochner owned a small bakery in Utica, New York. In April 1901, Lochner was arrested and charged with violating the Bakeshop Act. One of his employees, Aman Schmitter, worked more than 60 hours in one week. The state trial court fined him $50 and sentenced him to 50 days in jail. Lochner appealed. Both state appeals courts upheld the law, citing a need to protect worker safety and public health. Lochner appealed his case to the Supreme Court.

Issue

Does a state law regulating maximum work hours violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Summary

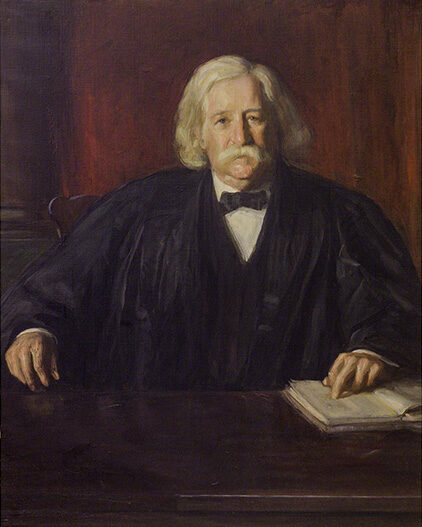

The Supreme Court invalidated the Bakeshop Law in a 5-4 decision on April 17, 1905. Justice Rufus W. Peckham wrote for the majority that the law’s interference with the right to contract between employer and employee was unconstitutional. While the Constitution does not explicitly mention liberty of contract, Justice Peckham stated that it is implied by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. According to the majority, the freedom to enter into a contract however and with whomever you please falls under the government’s protection against any statute that infringes on an individual’s “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.”

Justice Peckham’s opinion for the Court stated that the health risks associated with the baking industry do not justify the state legislature’s interference with the right to labor or Lochner’s liberty of contract. Therefore, the majority decided the Bakeshop Act was an improper use of the state’s power to legislate for the health, safety, and welfare of the public.

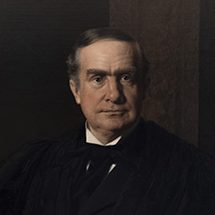

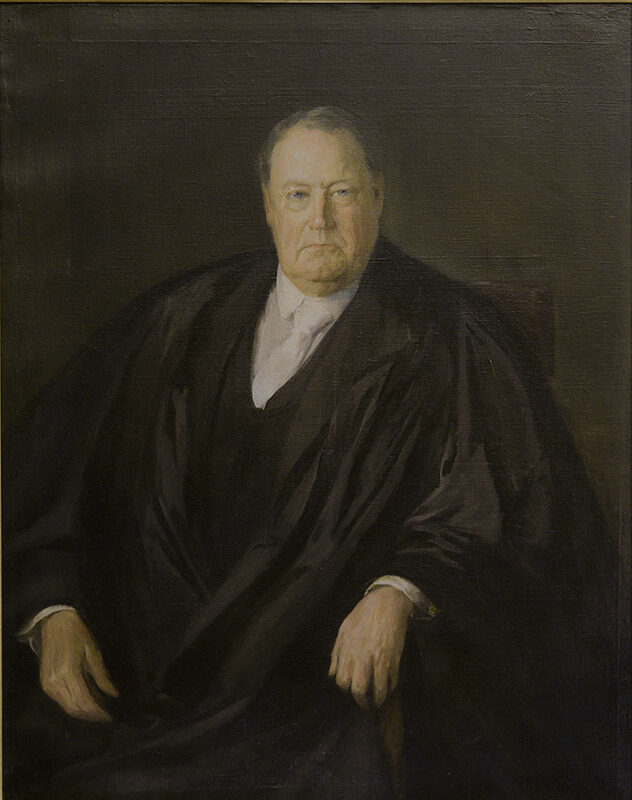

Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented, joined by Justice Edward D. White and Justice William R. Day. Unlike Justice Peckham, they believed the state legislature’s determination that the conditions in bakeries were a legitimate public health concern was reasonable. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes filed a separate dissenting opinion. He criticized the majority for using the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to protect a right not explicitly written in the Constitution.

Precedent Set

Lochner v. New York initiated an era in which the courts protected economic freedom and liberty of contract by invalidating state and federal laws that inhibited business. By 1937, however, the Court’s decision in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish upheld the constitutionality of a state minimum wage law and reversed Lochner. The period from 1905 to 1937 is sometimes called the “Lochner Era.”

Additional Context

The Court’s majority and dissenting opinions in the Lochner case demonstrate two methods of jurisprudence judges use to interpret the Constitution. The majority opinion applied a school of thought that later became known as substantive due process. “Liberty of contract” is not written in the Bill of Rights, but using substantive due process, the majority argued that it is implied in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. That clause protects against the government’s taking of an individual’s “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The Court has since used substantive due process for a variety of reasons, such as recognizing a right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965).

In contrast, the dissenting opinion relies on a strict constructionist approach to interpreting the Constitution. That school of thought is that courts should apply the Constitution exactly as written. Strict constructionists believe substantive due process lends itself to creating law, rather than applying it. Laws, they argue, should only be created by elected officials and the legislative branch. Debate over which method of jurisprudence should prevail—substantive due process or strict constructionist—continues today.

Furthermore, the decision frustrated Progressive and New Deal reformers who believed government intervention was the best solution to society’s social and economic problems. To these reformers, and other critics, the Lochner decision became an undesirable example of judicial activism—the practice of making a judicial decision based on personal policy views instead of the law. By striking down a justifiable state regulation, critics feared that the Court’s majority inappropriately stepped into politics. In the eyes of reformers, the Lochner decision protected businesses over the rights of workers and supported laissez faire ideology. Though this was the perception of reformers, the Supreme Court upheld approximately as many regulations as it overturned during this era.

Decision

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

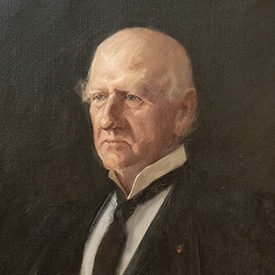

Fuller

-

Harlan

-

Brewer

-

Brown

-

White

-

Peckham

-

McKenna

-

Holmes Jr.

-

Day

-

Majority Opinion

Rufus W. PeckhamRead More CloseUnder such circumstances the freedom of master and employee to contract with each other in relation to their employment…cannot be prohibited or interfered with without violating the Federal Constitution.

-

Dissenting Opinion

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.Read More CloseThis case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain. If it were a question of whether I agreed with that theory, I should desire to study it further and long before making up my mind. But I do not conceive that to be my duty, because I strongly believe that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a majority to embody their opinions in law.

Discussion Questions

- How did population growth in the late nineteenth century impact the development of the bread baking business?

- Laissez faire refers to a policy of minimal government interference in the economy, and was the prevailing economic ideology during this time period. How did the majority opinion in Lochner reflect laissez faire?

- Do you think that states should be able to regulate working hours or should businesses and workers have the freedom to decide how long to work? Explain.

- Why did critics disagree with the majority opinion in Lochner?

Extension Activity

Read the case summary of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). Compare judicial activism in this case with Lochner. How are the cases similar? How are they different?

Sources

Special thanks to scholars David Bernstein and Paul Kens for their review, feedback, and additional information.

Featured Image: Photo of Lochner’s Home Bakery, courtesy of Josh Blackman and the Oneida County Clerk’s Office.

Bernstein, David E. “Lochner and Constitutional Continuity.” Journal of Supreme Court History 36, no. 2 (2011), p. 116-128.

Ely Jr., James W. The Fuller Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacies. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, 2003.

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905).

Kens, Paul. Lochner v. New York: Economic Regulation on Trial. Lawrence, KN: University Press of Kansas (1998).

Kens, Paul. “Lochner v. New York: Rehabilitated and Revised, but Still Reviled.” Journal of Supreme Court History 20, no. 1 (1994), p. 31-46.