Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

Significant Case

The first Supreme Court case linking reproduction to the right to privacy.

Background

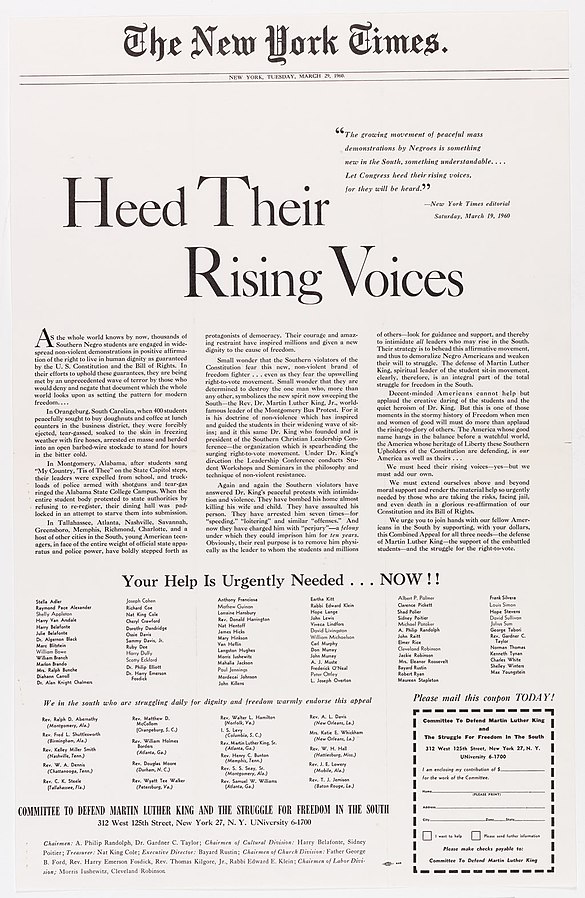

In the late 1860s, Civil War veteran Anthony Comstock moved from rural Connecticut to New York City. At the time, cities were growing rapidly because of immigration and advancements in transportation and technology. Meanwhile, an explosion in publishing, fueled by increases in literacy, introduced a significant number of new books into circulation. Well-established medical supply companies began advertising contraceptives through the mail. These activities did not align with Comstock’s values, and he dedicated his career to combatting what he perceived as immorality. Working with wealthy donors at the Young Men’s Christian Association, he pioneered new definitions of obscenity. While the law had said almost nothing about contraception before, Comstock promoted criminal laws making information and items related to abortion and contraception the quintessential example of the obscene. His work culminated in the passage of the federal Comstock Act of 1873, which prohibited “obscene” publications, and banned the mailing of “any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception.”

Comstock’s work significantly influenced American society. Twenty-four states passed their own versions of Comstock laws, and Connecticut’s was one of the most restrictive. In 1879, the state banned the use of “any drug, medicinal article, or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception.” Starting in 1923, the Connecticut Birth Control League, later to be known as the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC), challenged the law. They petitioned the state legislature to repeal the statute, opened birth control clinics, and, when the clinics were inevitably shut down, provided transportation for women to receive contraceptive care in other states. By the 1940s, the reformers appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

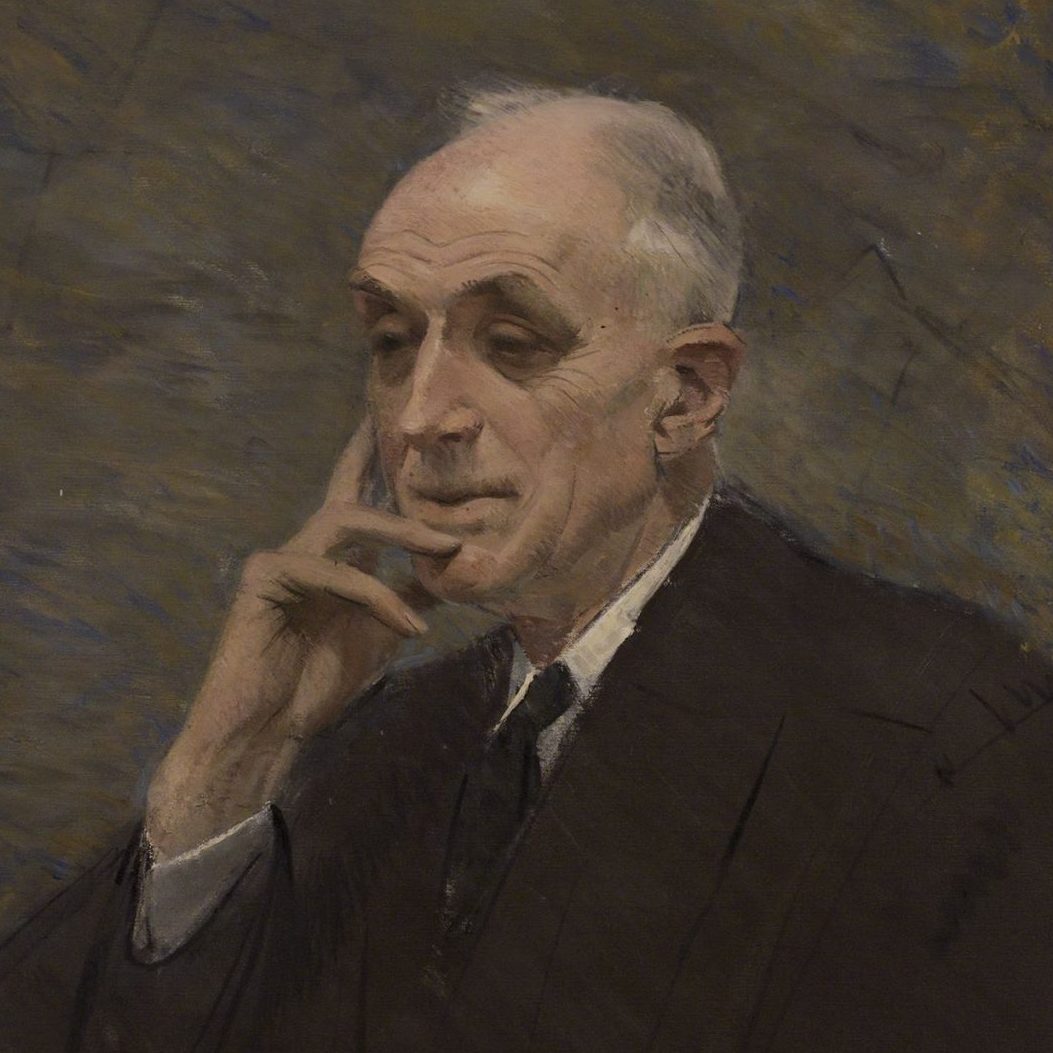

The Court declined twice to issue a ruling on the 1879 statute. It dismissed an appeal in Tileston v. Ullman (1943), stating that the appellant did not have standing (the grounds to file a lawsuit). Then, in Poe v. Ullman (1961), the Court noted that in the 82 years since Connecticut enacted the law, no one had ever used it in a prosecution. Justice Felix Frankfurter referred to the law as “dead words” that did not require a judgment from the Court. After the justices dismissed the issue on June 19, 1961, Estelle Griswold, the PPLC’s executive director, announced the organization would open a birth control clinic in defiance of the statute. She stated, “it is our hope that someone will complain and that the State Attorney in New Haven will act to close the center. We shall then carry our case to the U.S. Supreme Court and this time we feel they shall have to make a decision.”

Facts

Griswold opened a birth control clinic in New Haven, Connecticut with Dr. C. Lee Buxton, a gynecologist from the Yale School of Medicine. Buxton was a plaintiff in a 1959 case where the Connecticut Supreme Court upheld the 1879 statute, and he was involved in Poe as the plaintiff’s doctor. The clinic opened on November 1, 1961. It provided information, instruction, and medical advice on contraception to married persons. At the time, national Planned Parenthood guidelines stated facilities should not offer contraceptive care to unmarried women, so the clinic followed this practice.

Within a day of opening, a local New Haven man, James G. Morris, filed a complaint against the clinic. He described himself as “just an ordinary citizen with five children who was never elected to office,” and stated that he was “100 percent against birth control because it’s immoral.” Two detectives from the New Haven Police went to the clinic to open an investigation. They interviewed Griswold, who walked them through the facility and explained its operations. One of the detectives wrote in his investigation report that “Mrs. Griswold informed us that she realized that this…was a violation of the law.”

On November 10, 1961, the detectives returned to the clinic with warrants for the arrests of Buxton and Griswold. The charges stated that they “did assist, abet, counsel, cause, and command certain married women to use a drug, medicinal article and instrument, for the purpose of preventing conception.” On January 2, 1962, the Sixth Circuit Court of Connecticut found both defendants guilty and fined them $100 each. The Connecticut Supreme Court affirmed the decision. As planned, Griswold and Buxton appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Issues

- Does the Constitution protect a right to privacy?

- Does Connecticut’s 1879 law banning the use and distribution of contraception violate the Constitution?

Summary

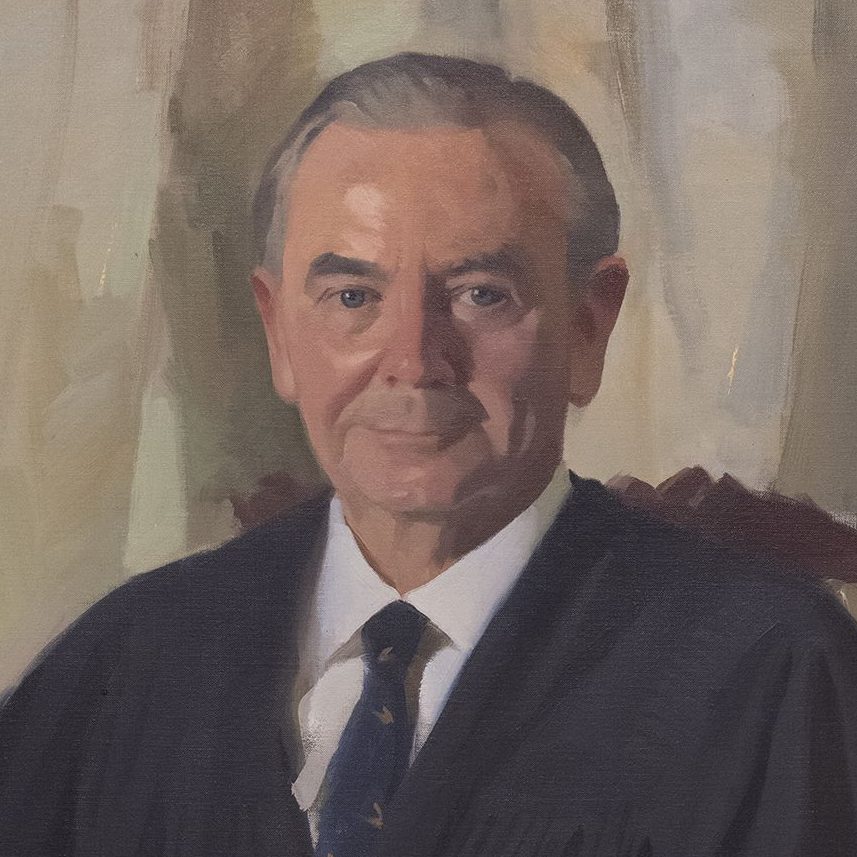

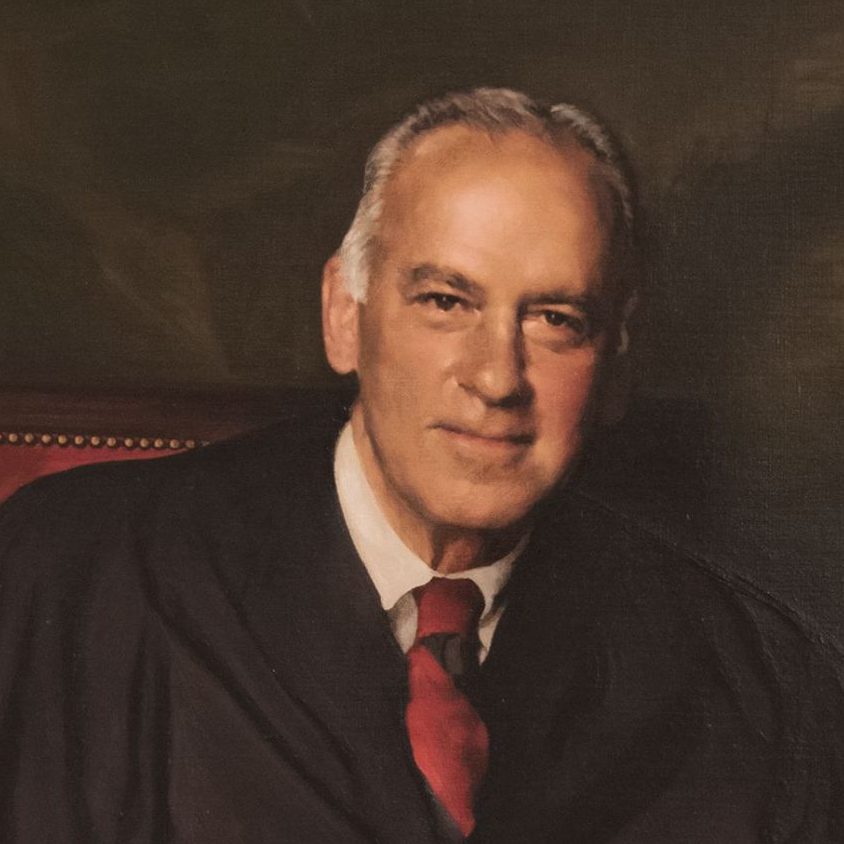

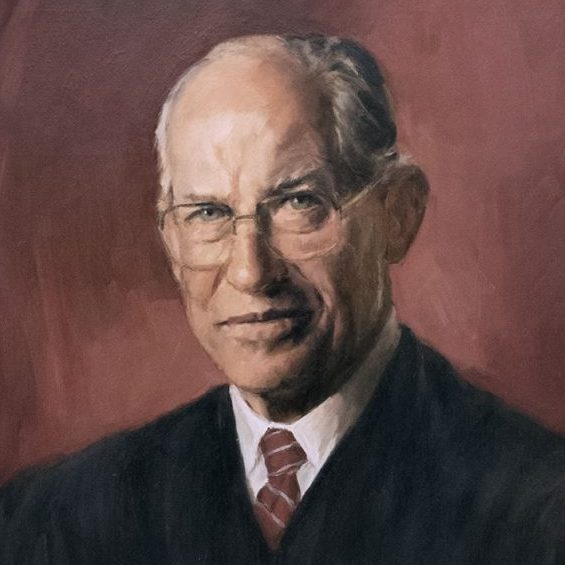

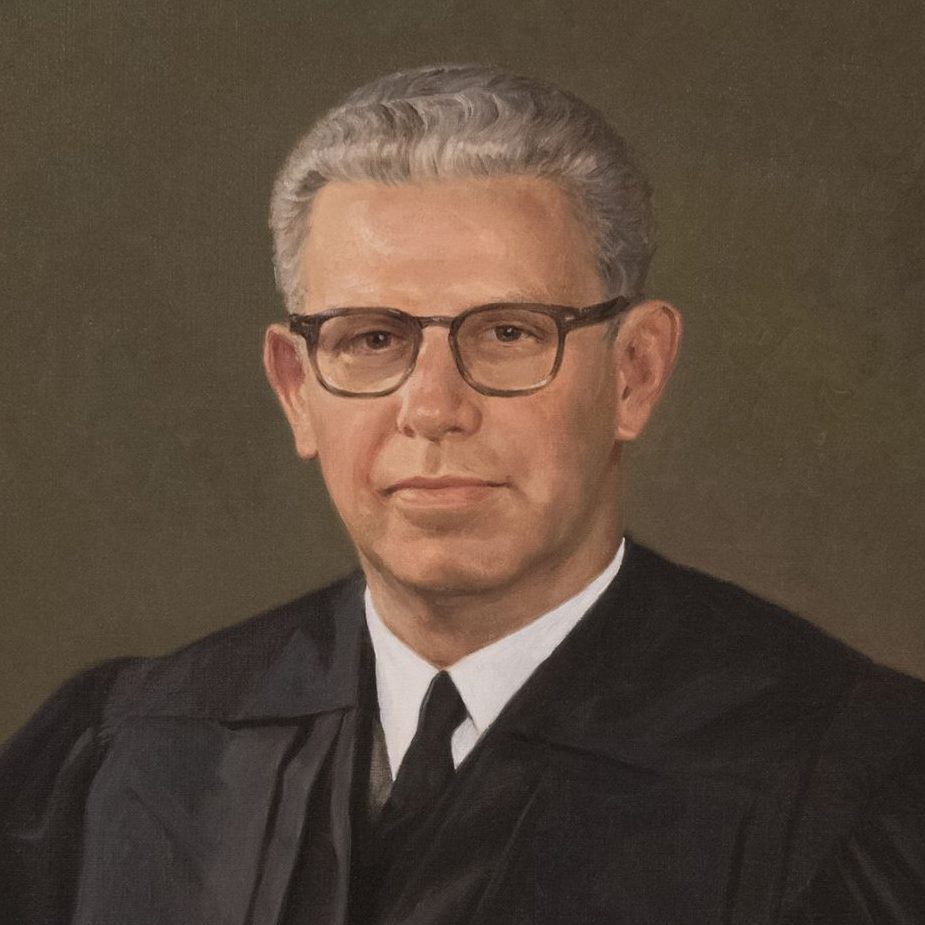

On June 7, 1965, the Supreme Court of the United States held in a 7-2 decision that the Connecticut statute violated a right to privacy broad enough to cover married couples’ decision to use contraception. While the Constitution does not explicitly mention a right to privacy, Justice William O. Douglas stated in his majority opinion that “various guarantees [from the Bill of Rights] create zones of privacy.” To support this, he cited cases where the Court recognized and protected an individual’s right to privacy from the government. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) challenged the state of Alabama’s requirement that it disclose its membership lists. The Court held in NAACP v. Alabama (1958) that NAACP members have a right to associate freely with others in pursuing their own private interests. This freedom of association, Douglas stated, was a “peripheral First Amendment right.” He further clarified that “the association of people is not mentioned in the Constitution nor the Bill of Rights…Yet the First Amendment has been construed to include certain of those rights.” Douglas argued similarly that the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments to the Constitution imply guaranteed “zones of privacy.” Mapp v. Ohio (1961), for instance, held that the Fourth Amendment established a “right to privacy” in its protection against unreasonable search and seizure. He concluded that all of these protections apply to marriage, noting that “marriage is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.” Douglas also suggested that the specific decision at issue for married couples—whether to use birth control in the privacy of their homes—was especially private. “Would we allow the police,” Douglas asked, “to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives?” Justices Arthur Goldberg, John M. Harlan, and Byron White authored concurring opinions—though they disagreed on the constitutional basis for the decision, they agreed that the law was unconstitutional and supported the majority opinion. Justice Potter Stewart wrote a dissent, which Justice Hugo L. Black joined. The dissenters acknowledged that the law was “uncommonly silly,” but concluded that there was nothing in the Constitution to invalidate it. The constitutional way to overturn the law, they argued, was for citizens to persuade their elected representatives to repeal it.

Precedent Set

Griswold v. Connecticut marked the first time that the Court recognized a Constitutional right to privacy. The Supreme Court heard two related cases the following decade that cited this precedent. In Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), the Court held that a statute banning unmarried persons from accessing contraception violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Griswold had not been clear about whether its right to privacy primarily reflected the importance of marriage or the significance of making decisions about childbearing. Eisenstadt answered that question. “If the right of privacy means anything,” wrote Justice William Brennan for the Court, “it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.” The next year, the Court held in Roe v. Wade (1973) that “criminal abortion laws…violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects against state action the right to privacy, including a woman’s qualified right to terminate her pregnancy.” Roe was overturned by the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which cited Justice Stewart’s dissent, in 2022.

Additional Context

The Court’s majority and dissenting opinions in the Griswold case demonstrate two types of jurisprudence about how to interpret the Constitution because it does not explicitly name a right to privacy in the Bill of Rights. These schools of thought are known as substantive due process and strict constructivism.

The majority opinion embraced substantive due process. It found an implied right to privacy based upon a combination of provisions in the Constitution, including the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection against the government’s taking of an individual’s “life, liberty, or property without due process of law”.

The dissenting opinion, however, is rooted in strict constructivism, the idea that courts should apply the Constitution exactly as written. Strict constructivists believe substantive due process lends itself to creating law, rather than applying it. Laws, they argue, should only be created by elected officials and the legislative branch. Debate over which jurisprudence should prevail continues today.

Decision

7-2 in favor of Griswold

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

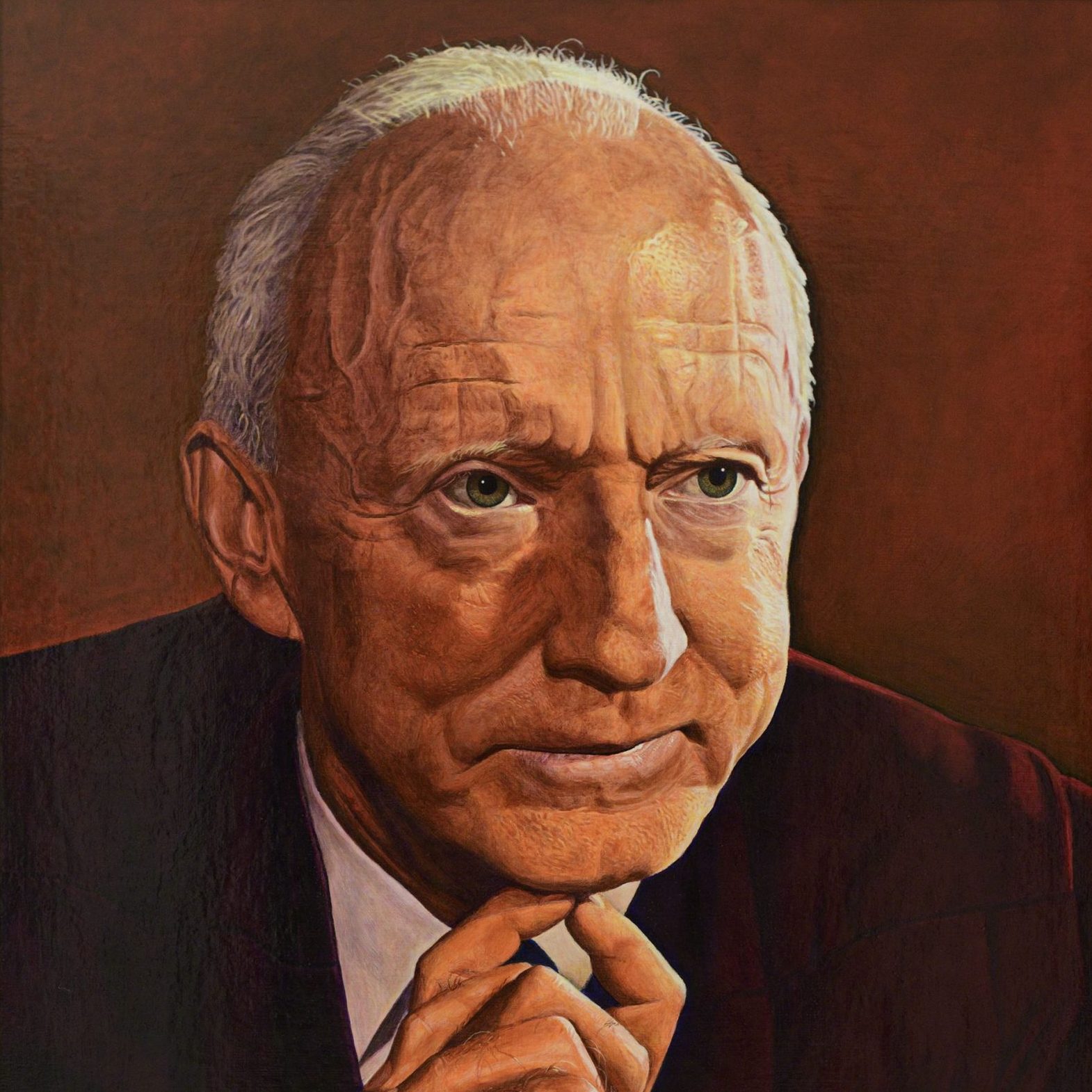

Warren

-

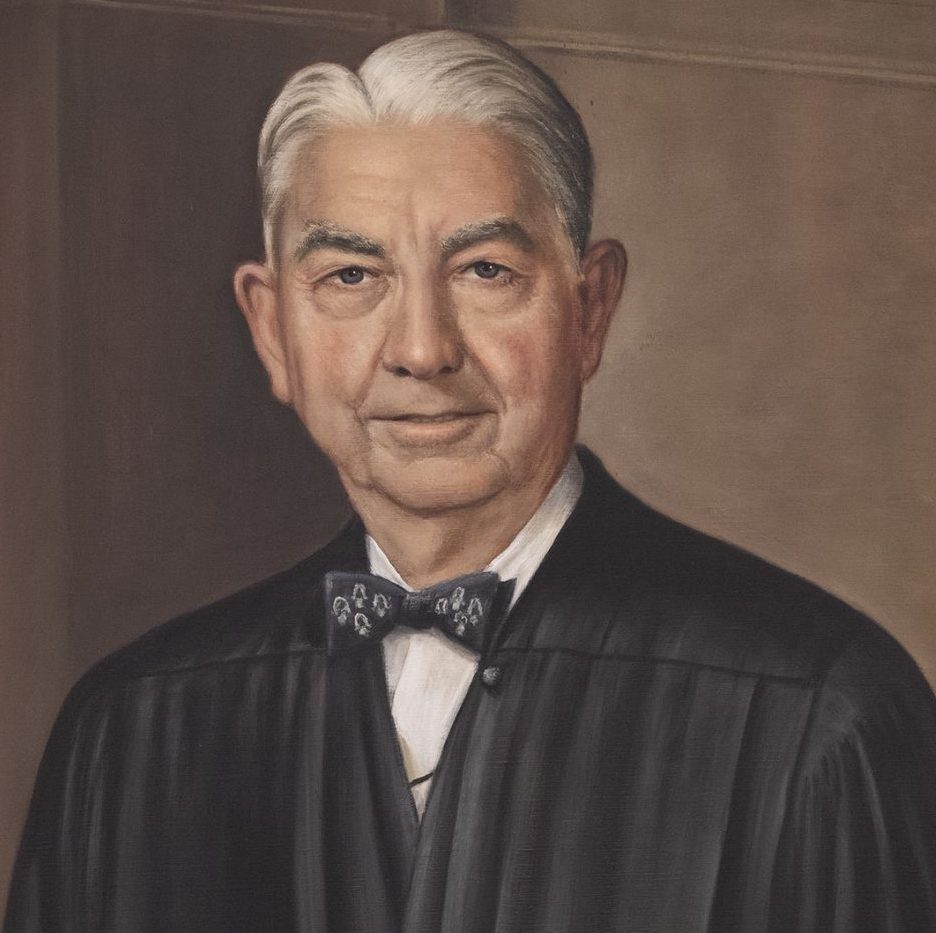

Black

-

Douglas

-

Clark

-

Harlan II

-

Brennan

-

Stewart

-

White

-

Goldberg

-

Majority Opinion

William O. DouglasRead More CloseWe deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights—older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred.

-

Concurring Opinion

Byron R. WhiteRead More CloseIn my view, this Connecticut law, as applied to married couples, deprives them of “liberty” without due process of law, as that concept is used in the Fourteenth Amendment. I therefore concur in the judgment of the Court reversing these convictions under Connecticut’s aiding and abetting statute.

-

Dissenting Opinion

Potter StewartRead More CloseSince 1879, Connecticut has had on its books a law which forbids the use of contraceptives by anyone. I think this is an uncommonly silly law….But we are not asked in this case to say whether we think this law is unwise…We are asked to hold that it violates the United States Constitution. And that I cannot do.

Discussion Questions

- Why did the federal and state governments start passing “Comstock Acts” in the 1870s?

- Why did the Supreme Court decline to issue a ruling on Connecticut’s 1879 obscenity law in 1943 and 1961?

- Why is it significant that the Supreme Court determined the Constitution protects a right to privacy?

- Why do you think the actions protected by the right to privacy continue to be debated today?

- Do you think the Constitution should be amended to explicitly include a right to privacy? Why or why not?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Mary Ziegler for her review, feedback, and additional information.

“An arrest in New Haven, contraception and the right to privacy.” Yale Medicine Magazine. 2007. https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/article/an-arrest-in-new-haven-contraception-and-the/.

“Anthony Comstock’s ‘Chastity Laws.” American Experience. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-anthony-comstocks-chastity-laws/.

CBS Reports. “Birth Control and the Law.” Aired May 10, 1962. Published on CPSAN. https://www.c-span.org/video/?443313-1/excerpt-birth-control-law.

“Comstock Act.” Women and the American Story. New York Historical Society. https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/fighting-for-equality/comstock-act/.

Cushman, Clare. Supreme Court Decisions and Women’s Rights. Washington, D.C: CQ Press, 2011.

Garrow, David J. Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe v. Wade. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

Gillette, Howard F. “Birth Control Clinic Opens in New Haven, Buxton Named Director.” Yale Daily News. 3 November 1961. https://ydnhistorical.library.yale.edu/?a=d&d=YDN19611103-01.2.3.

Featured image: Estelle Griswold and Cornelia Jahncke, June 7, 1965. The New Haven Museum. http://collections.newhavenmuseum.org/MADetailB.aspx?rID=MSS%20B62/1-Box%2054#Folder%20d&db=biblio&dir=WHITNEY.