Escobedo v. Illinois (1964)

Significant Case

The Supreme Court decision that affirmed a person has a Sixth Amendment right to consult a lawyer as soon as the police focus on them as a suspect

Background

During the Warren Court era (1953-1969), the Supreme Court decided many cases involving the constitutional rights of the accused during arrests, interrogations, and trials. These decisions prevented state and local enforcement from abridging the Fifth Amendment’s right not to speak to law enforcement and incriminate oneself and the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel.

For example, in 1963, the Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that the accused had the right to a lawyer in criminal felony trials under the Sixth Amendment. The decision required states to provide an attorney for defendants who cannot afford one. But it was still unclear at what point in a police interrogation a suspect could invoke their rights to an attorney and not speak to law enforcement. Police officers had an incentive to deny a suspect the right to counsel in the early stages of an investigation in the hopes that they would incriminate themselves or confess to the crime. Lower courts struggled to determine whether a statement of self-incrimination by a suspect in police custody had been voluntary. In Escobedo v. Illinois (1964), the Court decided whether the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel applied to the period when a suspect was in police custody for questioning but had not yet been charged with a crime.

Facts

On January 19, 1960, Manuel Valtierra was shot and killed. The Chicago Police Department arrested Benedict DiGerlando and Valtierra’s brother-in-law, Danny Escobedo. During his questioning, Escobedo declined to make a sworn statement and the police released him. Escobedo contacted a lawyer who advised him not to say anything to the police about the murder.

On January 30, the police arrested Escobedo again, based on the tip of a confidential informant. One of the officers informed Escobedo that DiGerlando, who was also in custody as a suspect in the murder, had accused him of shooting Valtierra. The officer urged Escobedo to confess. Escobedo asked for his lawyer to be present during questioning, but the police refused on the ground that he had not yet been formally charged. Although the lawyer was waiting outside the interrogation room, the police prevented him from talking to his client despite repeated requests from both Escobedo and his lawyer. The police also failed to inform Escobedo of his right to remain silent.

The police questioned Escobedo for over 14 hours. During the interrogation, they brought DiGerlando into the same room and urged Escobedo to accuse him of killing Manuel Valtierra. Escobedo admitted knowledge of the crime, speaking in Spanish to a Spanish-speaking officer. Under Illinois law, being an accessory to a murder, as Escobedo had admitted, had the same punishment as committing the murder. This admission formed the basis of the confession that Escobedo made to the office of the state prosecutor. After incriminating himself, Escobedo was tried in court and convicted of the murder of his brother-in-law. He faced a 20-year sentence for first degree murder.

Escobedo appealed his decision to the Illinois Supreme Court, which initially ruled his confession inadmissible and reversed the conviction on February 1, 1963. However, after the state secured a rehearing of the case in May, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the conviction. This prompted Escobedo to appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Issues

- Does the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel apply to police interrogations at the state and local levels?

- Does the denial of counsel during a police interrogation render a confession inadmissible even if it is given before the defendant is formally charged?

Summary

The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the accused have a constitutional right to an attorney during police interrogations. Escobedo’s confession was found inadmissible and the Court overturned his conviction. Justice Arthur Goldberg noted in his majority opinion that, at the time of Escobedo’s confession, the police were no longer conducting a “general investigation” of an unsolved murder with Escobedo as a possible suspect. Rather, the interrogation was an attempt to force Escobedo to confess, which would increase his chances of being convicted at trial. Even though Escobedo had not yet been formally charged, in the eyes of the police, he was considered the “accused.” Accordingly, Escobedo was in significant legal trouble and the police should have granted his repeated requests to speak to his lawyer. “There is necessarily a direct relationship between the importance of a stage to the police for their quest for a confession,” wrote Goldberg, “and the criticalness of that stage to the accused in his need for legal advice.”

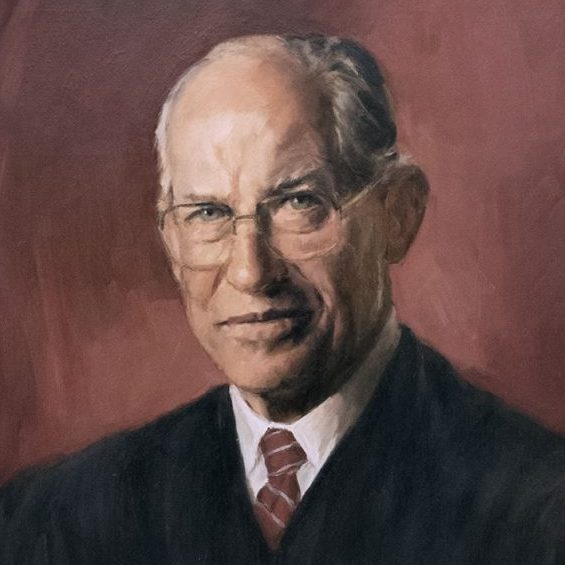

Four Justices dissented on the ground that the majority opinion undermined the authority of police officers. Justice John M. Harlan II wrote in his dissent in Escobedo that the rule outlined in the majority opinion was “most ill-conceived” and “that it seriously and unjustifiably fetters perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement.” Justice Potter Stewart agreed, arguing that the right to assistance by counsel should not be required until a formal proceeding, such as an indictment, is begun. The majority opinion “frustrates the vital interest of society in preserving the legitimate and proper function of honest and purposeful police investigation,” Stewart wrote.

Precedent Set

The ruling in Escobedo v. Illinois applied the Sixth Amendment right to counsel to states in interrogations. In particular, the Court established that after an arrest a suspect has the right to request a lawyer during police interrogations, even if the suspect has not been formally charged. Escobedo expanded the right to legal counsel established in the Court’s previous decision in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), which required states to provide an attorney to people in criminal trials who cannot afford one.

Additional Context

In the Escobedo decision, the right to a lawyer during a police interrogation stemmed from the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel. It soon led to the Warren Court’s landmark decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), which established the constitutional right to be informed of one’s right to remain silent when questioned by the police. However, unlike Escobedo, the Court’s opinion in Miranda rested on the Fifth Amendment right to avoid self-incrimination.

The majority’s approach in Gideon, Escobedo and Miranda was controversial. Criminal justice reform advocates hoped that these decisions would reduce police misconduct and wrongful convictions. Critics, however, felt that these rulings would make police work more difficult and allow criminals to evade prosecution.

Danny Escobedo was convicted in 1968 of selling heroin and sentenced to 14 years in prison. In 1986, he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for attempted murder.

Court Opinions

The Court issued a 5-4 decision in favor of Escobedo.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

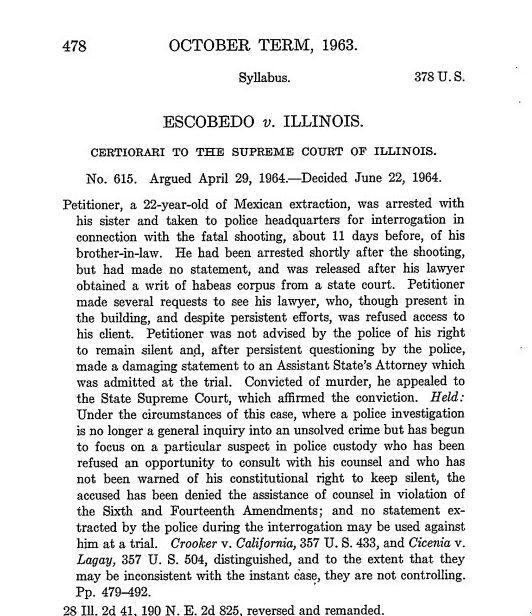

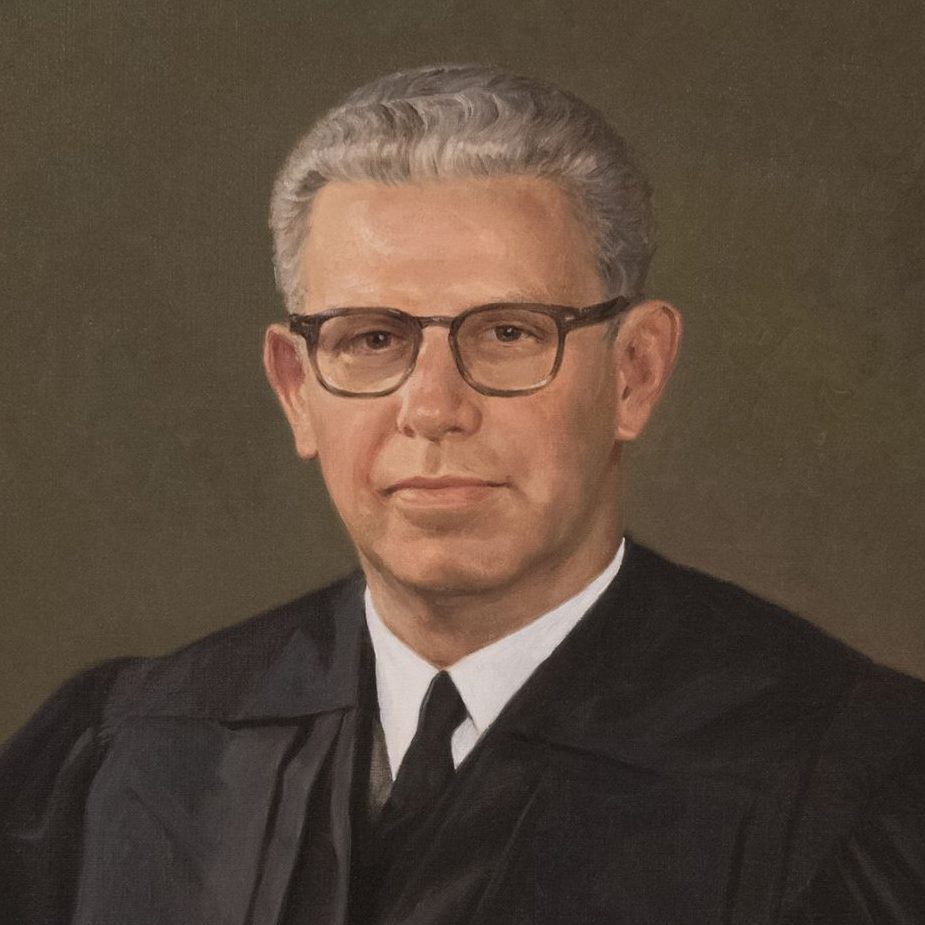

Warren

-

Black

-

Douglas

-

Clark

-

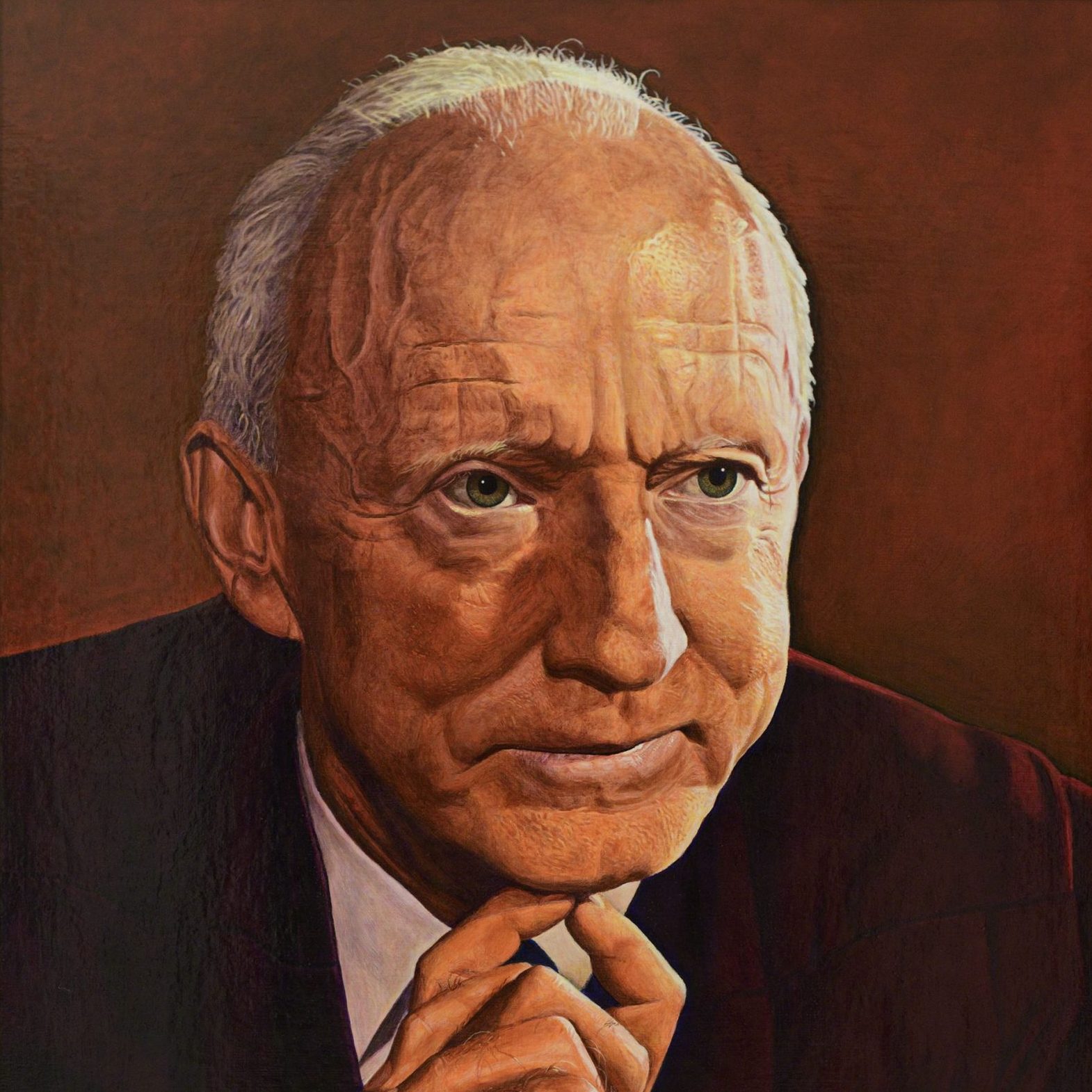

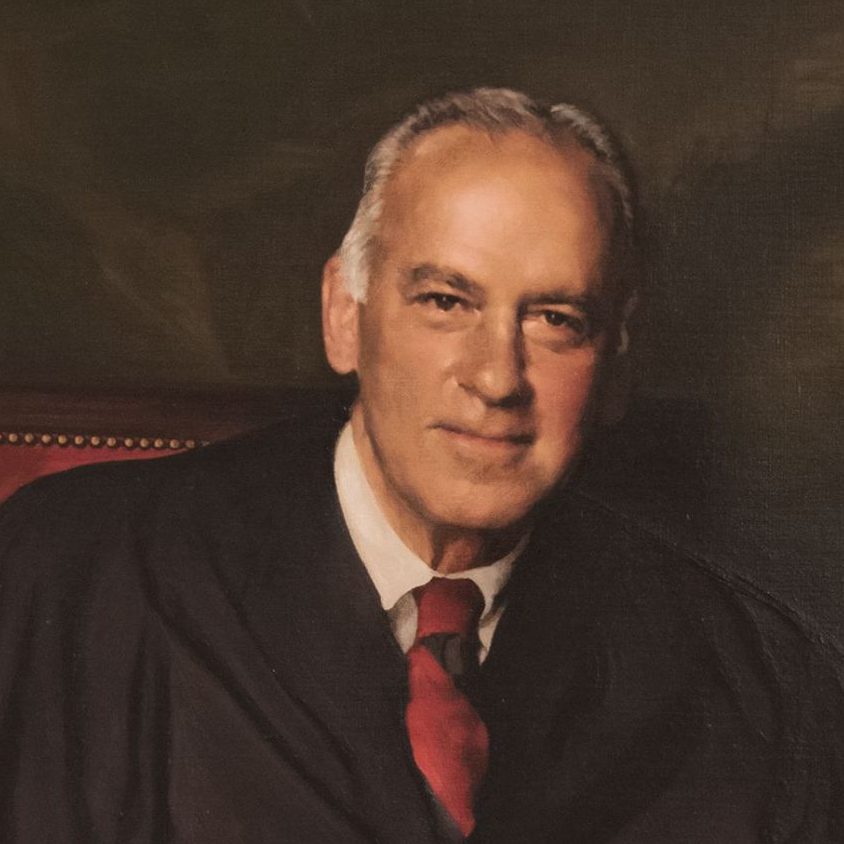

Harlan II

-

Brennan

-

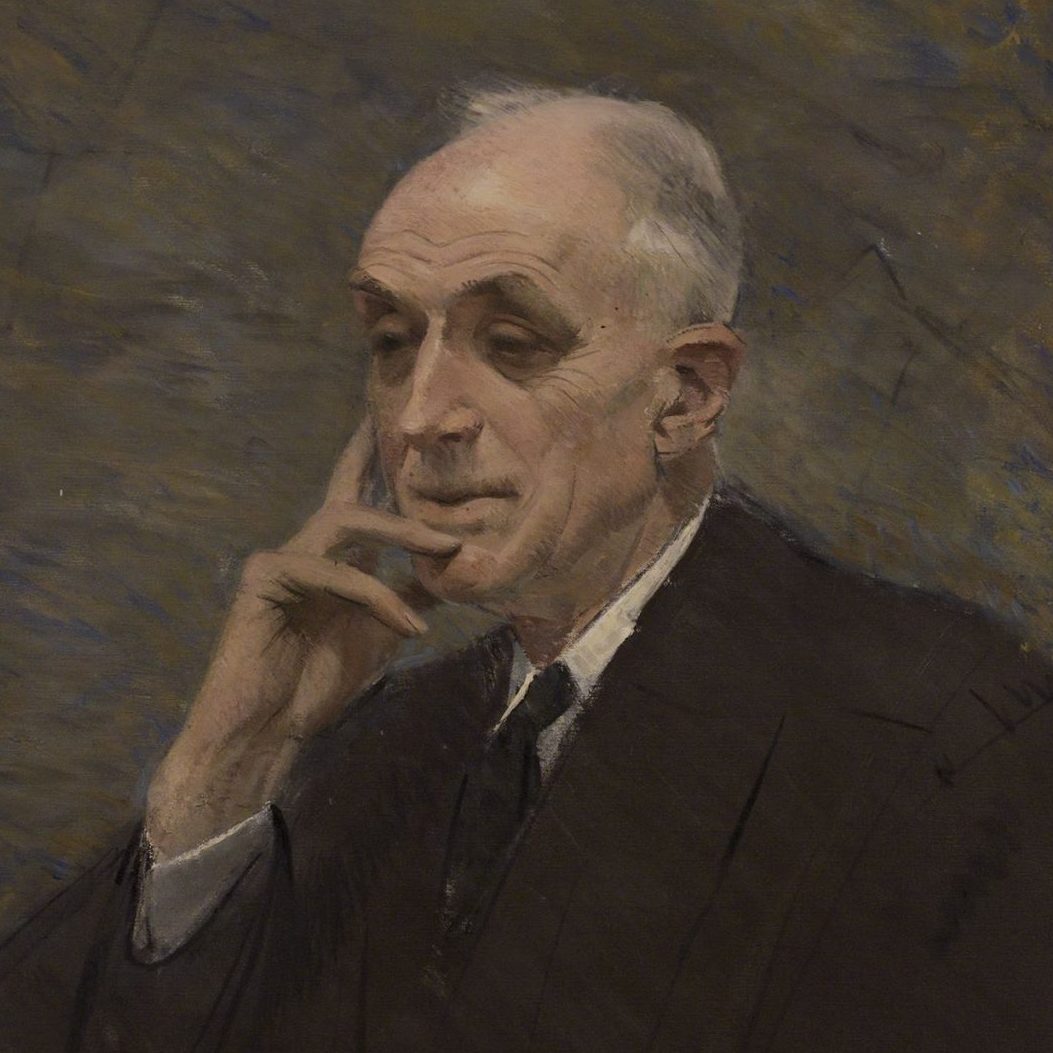

Stewart

-

White

-

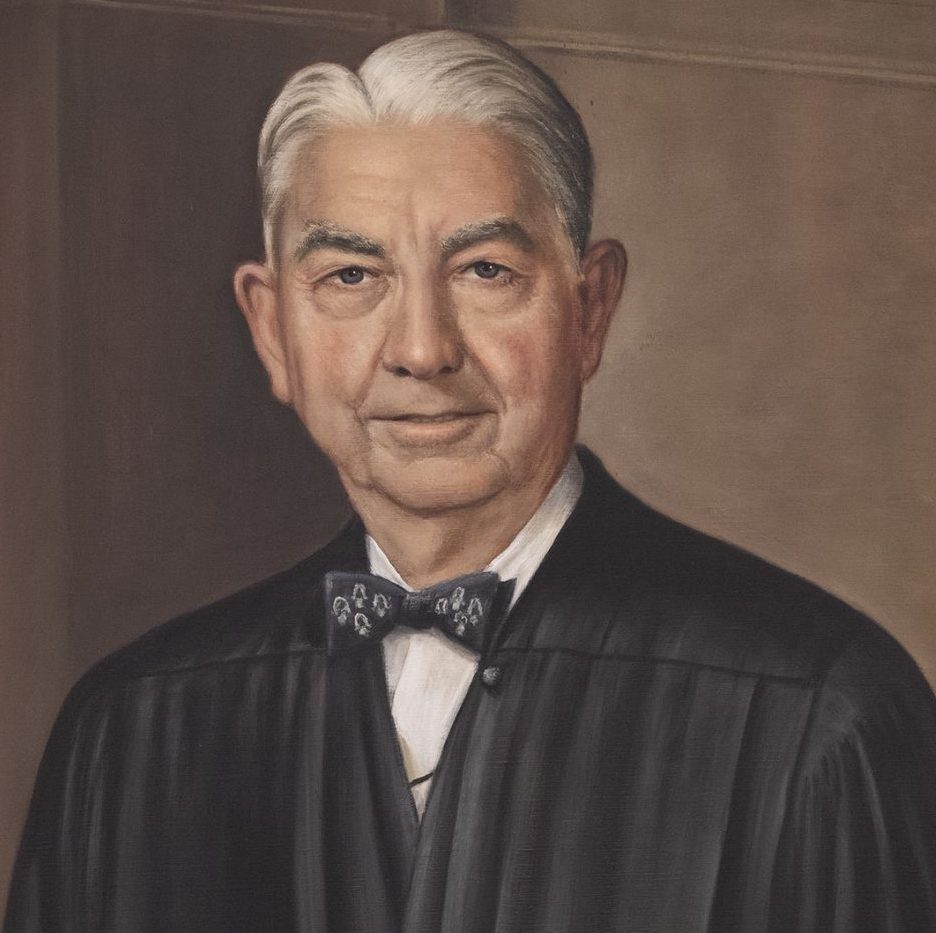

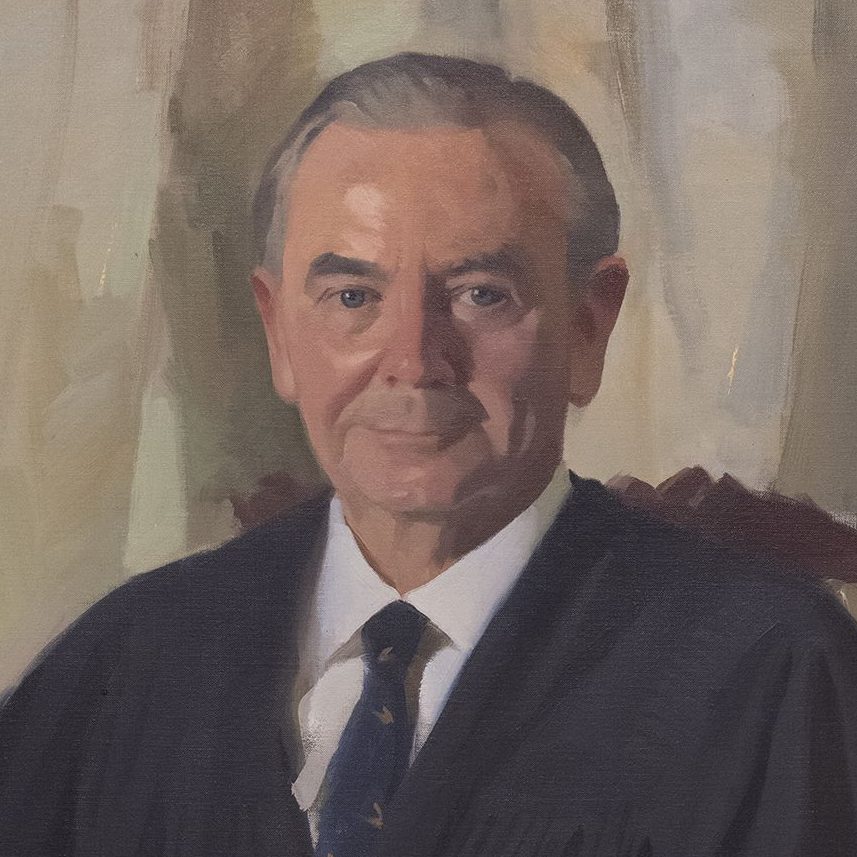

Goldberg

-

Majority Opinion

Arthur J. GoldbergRead More CloseWe hold only that, when the process shifts from investigatory to accusatory—when its focus is on the accused and its purpose is to elicit a confession—our adversary system begins to operate, and, under the circumstances here, the accused must be permitted to consult with his lawyer.

-

Dissenting Opinion

John Marshall Harlan IIRead More CloseI think the rule announced today is most ill-conceived, and that it seriously and unjustifiably fetters perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement.

Discussion Questions

- How did the decision in Escobedo change the way that the Sixth Amendment applied in cases involving state and local law enforcement?

- Do you think the Justices could have decided Escobedo under the Fifth Amendment instead of the Sixth Amendment? Why or why not?

- Why was the majority opinion in Escobedo controversial?

- The dissent said the ruling “fetters [restrains] perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement.” In what ways can protecting the rights of the accused make the task of law enforcement more difficult?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Brad Snyder for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Hall, Livingston. Modern Criminal Procedure (West Publishing Company, 1969), 484-496.

Hartman, Gary R., Roy M. Mersky, and Cindy L. Tate. Landmark Supreme Court Cases: The Most Influential Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States (Infobase Publishing, 2014), 159-160.

Ruschmann, Paul. Miranda Rights (Infobase Publishing, 2007), 41.

Hall, Kermit, ed. The Oxford Guide to the Supreme Court, 301.

“Escobedo Sentenced to 11 Years for Attempted Murder,” The Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1987.