Bessie Margolin

Life Story: 1909-1996

The daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants who dedicated her four decades of government service to fighting for workers’ rights

Background

Bessie Margolin was born on February 24, 1909 in New York City. Her parents, Rebecca and Harry, immigrated from Russia to escape religious persecution. Within a few years, they escaped the crowded city and moved south to Memphis, Tennessee. Here, they found a small community of other Yiddish-speaking, Russian-Jewish immigrants. Bessie’s mom died shortly after the birth of her younger brother. Her dad, now a widower, could not provide for the family. In 1913, he sent Bessie and her older sister Dora to the Jewish Orphans’ Home in New Orleans, followed by their brother one year later. The children lived in the home for the next 12 years.

Living in the Home created significant educational opportunities for Bessie. It established the nearby Isidore Newman Manual Training School to provide prestigious college preparatory education to its wards. At Manual, Bessie was nicknamed “Brightest Girl” for earning A’s in every subject. She coedited the school’s literary magazine, sang in glee club, and led the debate club and girls’ student council. She graduated at age 16 in 1925, and gave the speech at the ceremony. The caption on her senior yearbook photo was “Knowledge is power.”

Bessie’s strong academic performance in high school earned her a scholarship to Newcomb College, an all-women school in New Orleans. During her sophomore year, she transferred to Tulane University. As one of the top 10 students in her class at Newcomb, Bessie earned a spot, then rare for a woman, in Tulane’s combined undergraduate and law degree program, which she completed in five years. Bessie was the only woman in the entire law school in the fall of 1927. While there, she became an honors student, an editor on the law review, and volunteered at the orphanage where she grew up. She graduated in June of 1930, second in her class. After graduation, Bessie moved to Connecticut to be a research assistant at Yale University Law School. While there, she became the first woman to win a prestigious stipend to study law, giving her unusual financial security during the Great Depression. She graduated with her doctorate in law in 1933 and moved to Washington, D.C.

Early Career

At the same time Bessie moved to D.C., the federal government, led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, launched the New Deal. “The New Deal” collectively referred to hundreds of programs created to help alleviate the social and economic problems created by the Great Depression. The initiative opened millions of new jobs across the country. Bessie started work as a research attorney for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a program designed to bring electricity to rural areas. Because the TVA created unprecedented government involvement in local economies, it faced several legal challenges to its existence, one of which was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States. In Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority (1936), the Court held that Congress did not abuse its power by creating the TVA. Though Bessie did not argue the Ashwander case herself, she played a crucial role in researching and writing the successful legal arguments, while winning respect and praise from her all-male colleagues. The extent and quality of her work also earned her a promotion and a pay raise. At this time, women accounted for just two percent of all lawyers in the nation. When Bessie left the TVA, 10 years passed before the agency hired another woman lawyer.

In 1939, Bessie moved from the TVA to the Labor Department, where she would spend the rest of her career. She started as a senior litigation attorney at the Wage and Hour Division, where she helped implement another New Deal creation, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). She requested a salary of $5,600, but was told that was too much “for a girl.” She accepted a salary of $5,000, the same amount she made working at the TVA. At the time, legislation like the FLSA was new. Never before had the United States government been so involved in regulating businesses and workplace protections for its people. Lawyers like Bessie represented the interests of millions of working people by holding employers accountable for following laws designed to protect employees from unfair practices.

Bessie quickly realized that male lawyers with fewer qualifications than she were receiving promotions. She commented, “A woman is simply not considered for the high ranking positions in the Solicitor’s Office.” Bessie wrote a complaint to Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor and the first woman ever to hold a cabinet position. Perkins approved Bessie’s promotion to assistant solicitor within the month.

Supreme Court Advocacy

As an assistant solicitor, Bessie was responsible for appearing in court to defend challenges to the Department of Labor’s policies. She argued over 150 cases in the circuit courts, and argued 24 times at the Supreme Court, where only 24 women had ever argued before her. Her oral arguments in cases like Phillips v. Walling (1945), Rutherford Food Corporation v. McComb (1947), 10 East 40th Street Building, Inc. v. Callus (1945) shaped the country’s interpretation of the FLSA. Bessie’s work helped clarify key workers’ rights questions such as eligibility for coverage and overtime pay under the FLSA. She left an impression especially on Justice Robert H. Jackson, who sent her a handwritten note after her first oral argument. “You have every reason to feel satisfied with the way you took care of yourself under fire,” he wrote. “I’m sure there would be no dissent from the opinion that you should argue here often. One always feels low after an argument—at least I always did. But you need not.” Bessie reconnected with Justice Jackson when she served as a war crimes attorney during the Nuremberg Trials in 1946. Justice Jackson led the first trial, which prosecuted German officials accused of Nazi war crimes; Bessie helped create the courts that oversaw the subsequent trials of doctors, judges, and industrialists who also were accused of Nazi war crimes.

Back at the Labor Department, Bessie earned a promotion to associate solicitor in 1962, where she spent the final decade of her career. In this role, Bessie oversaw litigation for the new Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the Equal Pay Act (EPA). Congress passed the EPA in 1963, requiring for the first time that employers give men and women in the same workplace equal pay for equal work. It was the Labor Department’s responsibility, under Bessie’s leadership, to defend the implementation of this law in the courts. Bessie and her team of lawyers represented thousands of women workers seeking fair payment under the EPA. The Supreme Court did not hear an EPA case until after Bessie’s retirement, but her work, especially in Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Co. (1970), provided the legal foundation for the lawyers that followed. In Shultz, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey held that the Wheaton Glass Company must pay restitution for wages withheld from female employees dating back to the start of the Equal Pay Act in March 1965. In all, Bessie oversaw 300 EPA cases resulting in four million dollars in back pay to 18,000 women. Her work on the EPA led her to become more involved in the growing women’s rights movement, and she attended the first meeting of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966.

Challenges

Bessie’s successful career did not come without its challenges. During the Red Scare, the FBI investigated her loyalty as a government employee. They flagged her as a potential communist because of her Russian heritage, positive remarks about Russian officials while she was in Nuremberg, and advocacy for workers’ rights. There was no evidence that Bessie was disloyal.

She also battled sexism throughout her career. As she neared graduation from Yale, she inquired with her former professor at Tulane about a potential teaching job. He warned that as a woman, she would struggle to find a job as a law professor. To help persuade the TVA to hire her as its first female attorney, one of her references assured the hiring manager that she would focus on her career and not be “deflected by consideration of marriage.” Later on, Bessie conducted another search for a professor position. Before 1950, only 5 women had full-time or tenured positions as law professors. In 1953, five years after she began her search, she accepted her only offer. American University offered Bessie, a Supreme Court advocate with 20 years experience working in the Labor Department, a course about wills. She taught for only two semesters. Then, in 1962, she campaigned to become a federal judge. At the time, only two women served on the federal bench. President Lyndon B. Johnson seriously considered Bessie for different openings, but ultimately filled all of the vacancies for which she applied with men.

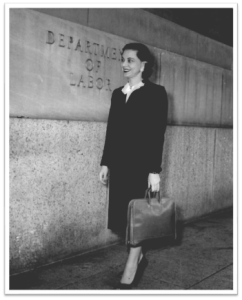

Even in the face of gender discrimination, Bessie embraced her femininity. She advised the new members of her college sorority that a woman lawyer “must aim to become one of the men, without, however, becoming masculine and overly aggressive in her approach.” In 1948, she appeared in Glamour magazine, representing the 0.01 percent of the 18 million working women who were lawyers and judges.

Legacy

Outside of her career, Bessie led a busy social life. She was “Aunt Bess” to four nephews, all who spent a summer with her in Washington, D.C. She hosted cocktail parties, bet on horse racing, played poker (even earning a regular spot at the TVA poker nights with her male colleagues). She never married, but she had several long-term romantic partners throughout her life.

Bessie retired from the Labor Department in 1972, after 40 years of government service. A lavish retirement party was a testament to her pioneering success and contributions to law. More than 200 people came to celebrate Bessie. The guest speaker was none other than Retired Chief Justice Earl Warren, who had presided over 15 of Bessie’s 24 Supreme Court arguments. In his remarks, Chief Justice Warren recognized Bessie’s decades of work on the Fair Labor Standards Act. “The bare bones of that Act,” he said, “would have been wholly inadequate without the implementation she forged in the courtrooms of our land.” Bessie continued to work during retirement. She returned part-time to the Solicitor’s office, served as an arbitrator, and briefly taught a Labor Standards and Equal Employment course at George Washington University Law School.

Bessie Margolin died of a stroke on June 19, 1996 at age 87. Throughout her 40-year career, she received several distinguished service awards and achieved one of the highest-ranking positions in the Labor Department. She argued before the Supreme Court 24 times (a number reached by fewer than ten women even today), and appeared in every one of the 11 circuit courts to argue a total of 150 cases. In her last working years, 10 of the 35 attorneys she supervised were women, including one attorney who became the first female Solicitor of Labor.

Discussion Questions

- How did living in the Jewish Orphans’ Home impact Bessie’s life?

- Gender norms are traditional expectations that society has of men and women and the roles they play at work and in the home. How did Bessie challenge gender norms for women? How do you think she felt to frequently be “the first” or “the only” woman in law school and throughout her legal career?

- Why do you think Bessie thought fair standards in the workplace were so important that she devoted most of her career to enforcing them?

- At the end of Bessie’s career, 10 of the 35 attorneys that worked for her were women. Why was this significant?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and author Marlene Trestman for her review, feedback, and additional information.

Trestman, Marlene. Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2016.

All photographs are courtesy of Marlene Trestman.