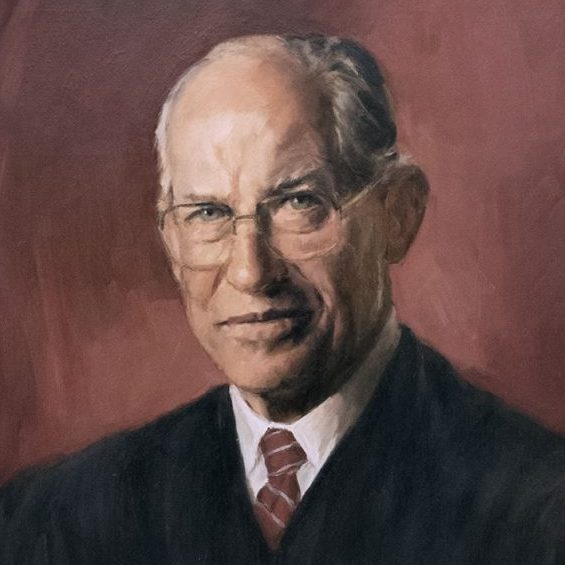

Byron R. White

Life Story: 1917-1993

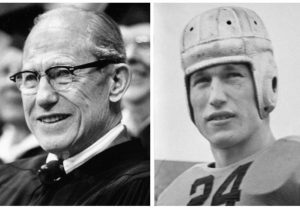

The professional football player, Rhodes scholar, Navy lieutenant commander, and United States Deputy Attorney General who became one of the longest-serving Justices of the Supreme Court

Background

Byron R. White was born in Fort Collins, Colorado on June 18, 1917. The Whites lived on a dirt road in the nearby farming town of Wellington, population 550. His father, A. Albert White, managed a local lumber company. Maude Burger, his mother, was the daughter of German immigrants. He had one older brother, Clayton “Sam” White. Neither parent graduated high school, which was not unusual for farming communities at the time. Byron recalled that “there was very little money around Wellington…you could say by the normal standards of today we were all quite poor, although we didn’t necessarily feel poor because everyone was more or less the same. Everybody worked for a living. Everybody.” He had his first job on a sugar beet farm at age 6, and worked physical jobs all throughout his childhood, like unloading lumber and shoveling coal. Starting in junior high, Byron and Sam rented 25 acres of land to farm sugar beets. They worked the land throughout the school year, which accommodated the farming community with breaks for the seasonal harvest.

Sam and Byron attended Wellington High School, and both made names for themselves in the classroom and on the field. Wellington never had more than 100 students, but always managed to cobble together the funds and players for sports teams. Byron played football, basketball, and ran track—the start of a successful athletic career. He also enjoyed fly fishing, swimming, and spectator sports, like horse racing. The Whites emphasized the importance of education, and Sam and Byron embodied this value. In addition to being student athletes, both excelled academically. Byron graduated Wellington High School in 1934 as valedictorian and, as a result, received a scholarship to the University of Colorado—the same honors his brother achieved four years prior. Byron’s athletic and academic excellence continued in college. He served as student body president and earned varsity letters in basketball, baseball, and football. His grades earned him a spot in Phi Beta Kappa, a prestigious honor society, and he once again graduated as valedictorian.

Byron’s college football career launched the small-town athlete, who learned to play on a team with hand-me-down uniforms, into lifelong fame. Sports journalists dubbed him “Whizzer” White, a nickname that followed him throughout his life (though Byron never liked it). He became an All-American and was named to the Collegiate Hall of Fame. Though he loved to compete, Byron had no interest in the fame that came with being a star athlete. He continued to pour over his schoolwork. Sam wrote to him from Oxford University in the United Kingdom, “you are to be commended for your great athletic record…I only hope you do not neglect your studies for football.”

As graduation approached, Byron received two conflicting offers. He won a Rhodes scholarship to attend graduate school at Oxford, like Sam. At the same time, he was selected by the Pittsburgh Pirates (now the Steelers) in the first round of the NFL draft. After months of deliberation, and a great deal of speculation from the press, he learned that Oxford would accommodate him: He could defer his acceptance for a semester, and play football during the fall. In 1938, Byron accepted a record-high $15,000 contract to play halfback for the Pirates, where he led the league in rushing for the season—a first for a rookie.

Byron left for England at the end of the football season and began at Oxford in January 1939. While abroad, he met and befriended John F. Kennedy, who was visiting his father, the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom. After two semesters, World War II began in Europe, and the university sent American students back home. When Byron returned to the States, he attended Yale Law School and played for the Detroit Lions. He balanced his studies while leading the NFL with 514 rushing yards. Then, in December 1941, the U.S. joined the war. He enlisted with the Navy, and became an intelligence officer stationed in the Pacific. Coincidentally, he crossed paths with Kennedy. Byron wrote the report on the sinking of Kennedy’s PT-109, a disaster that gave Kennedy the national war hero status that would later bolster his 1960 presidential campaign. The Navy awarded Byron a Bronze Star and discharged him from the reserves as a lieutenant commander on January 25, 1946.

Byron returned to Yale to finish his law degree, and graduated magna cum laude. After graduation, he and his girlfriend, Denver native Marion Lloyd Sterns, moved home to Colorado. The couple married on June 15 and later had two children. The same year, Byron received a coveted opportunity to clerk for Fred Vinson, the Chief Justice of the United States. Washington, D.C. became their home for the next year.

The Whites returned to Colorado at the end of the clerkship in 1947. Byron entered private practice for 14 years with the Denver law firm now known as Davis, Graham, and Stubbs. Most of his cases involved negotiating real estate deals, facilitating commercial transactions, and counseling corporate clients. He developed a reputation for his thorough research, and specialized in bankruptcy and tax law. Local sports writers wanted to report on the return of “Whizzer” White, but Byron declined interview requests. Being a celebrity did not interest him: he wanted to establish his legal career on his own professional merits. A college friend recalled Byron saying, “I want to establish my practice, contribute to the community, and keep my name out of the newspapers.” Indeed, during his 14 years in Denver, Byron volunteered his time for over a dozen organizations and charities.

Byron believed that “everyone in this country has an obligation to take part in politics. That’s the foundation, the most important principle, on which our system is built.” The Democratic Party of Colorado approached him several times about running for office, but he always declined. A private man, he preferred to work behind-the-scenes. He recalled, “every year after 1947 I worked on someone’s committee…It might have been a judge, a candidate for state legislature, or someone running for local office. I worked at it and I really got to know those people.” Despite his efforts to distance himself from football, “Whizzer White” was still a household name. The NFL elected him to the Hall of Fame in 1954.

Byron had a strong reputation working in state and local politics by the time his friend, John F. Kennedy, started campaigning for president. Byron organized the Colorado for Kennedy Campaign, and then the national Citizens for Kennedy. After Kennedy won the 1960 election, he appointed Byron as Deputy Attorney General of the United States. As the Department of Justice’s second-in-command, Byron processed more than 100 judicial candidates to fill an unprecedented number of vacancies in the federal courts. He also played a key role in the federal government’s response to violence that erupted alongside the Freedom Rides, a movement that challenged segregated bussing. After the FBI refused President Kennedy’s request to provide protection for the protesters, Byron sent 600 federal marshals to Alabama to patrol the city of Birmingham and protect the freedom riders.

The Supreme Court

After Justice Charles E. Whittaker retired in 1962, President Kennedy nominated Byron to the Supreme Court. The Senate quickly confirmed his appointment on April 11, 1962. The confirmation hearing was estimated to be just 15 minutes long. He was 44 years old, making him one of the youngest people to ever become a Justice.

As a jurist, Byron believed in judicial restraint. He carefully considered the role of the Court, and in his opinions, cautioned it from overstepping its power. Judges, he believed, decided cases—they were not meant to legislate. Byron treated each case individually, making it difficult for historians to define his judicial legacy. Byron was pleased by this fact. He remarked, “I don’t have a ‘doctrinal legacy.’ I shouldn’t.”

He also rejected the doctrine of substantive due process, which reflected his concern about the overreach of judicial power. This doctrine holds that there are fundamental rights that are implied in and protected by the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments which prohibit the government from depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The Court has applied substantive due process to establish rights not explicitly named in the Constitution. Byron disagreed with this approach. For example, while he did vote to strike down a state ban on contraceptives in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), he did not join the majority opinion that asserted a “right to privacy.” Instead, the legal reasoning in his concurrence concluded that the law “deprived [married] persons of liberty without due process of law.” Later, he dissented in Roe v. Wade (1973), where the Court upheld access to abortion, again citing a constitutional right to privacy. He called the decision “an exercise of raw judicial power.” There was, he concluded, “nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court’s judgment.” In the realm of criminal law, Byron dissented in Miranda v. Arizona (1966). In this criminal law case, the Court held that failure to read procedural warnings (“Miranda rights”) to a person taken into custody would invalidate evidence. Byron wrote that Miranda rights had “no significant support in the history…or in the language of the Fifth Amendment.” These views reflect a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution.

Over the course of his career, Byron played a key role in several civil rights decisions. He consistently supported the Court’s involvement in school desegregation. In 1979, he authored a majority opinion that upheld a district court’s order for systemwide school desegregation (Columbus Board of Education v. Penick). Eleven years later, in Missouri v. Jenkins (1990), he affirmed that federal courts can fund school desegregation plans with tax increases. In keeping with his adherence to judicial restraint, he insisted that the Equal Protection Clause and its supporting statutes required intentional discrimination. Inequality of results on its own, he wrote for the Court in Washington v. Davis (1976), did not violate the Constitution.

Off the bench, Byron built strong relationships with his clerks. He enjoyed conversation with them over walks to the Library of Congress, art museums, or coffee shops. The Justice demanded an intense work schedule from his team, with 12-hour days plus “light” Saturdays, but squeezed in some basketball during breaks. The Supreme Court is home to what is affectionately known as “the highest court in the land,” a basketball court on the top floor of the building. Here, the Justice unleashed his competitive side. A clerk remembered that when Byron was on the floor, “elbows and bodies would be flying every which way. Typically, the elbows belonged to the Justice and the bodies belonged to the rest of us.” Byron’s clerks also enjoyed his company on ski trips to the Whites’ home in Colorado, and received calls during times of illness or grief. Byron had about 100 law clerks over the course of his career, and kept in touch with nearly all of them.

Legacy

Byron retired on March 19, 1993 and returned to Denver, Colorado. On his last day, he said to his colleagues, “the Court is a great institution. It has been good to me.” In retirement, he occasionally served on appeals courts. He died on April 15, 2002 after complications from pneumonia. Over the course of his judicial career, Byron R. White served with three Chief Justices, 20 Associate Justices, eight presidents, and authored 1,275 opinions. He defied categorization, following a strong moral compass about the role of the judicial branch rather than aligning with any particular ideology. He also contributed greatly to conference discussions. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist stated that “given the force of his powerful intellect, the breadth of his experience, and his institutional memory, Justice White consistently played a major role in the Court’s discussion of cases at its weekly conference.”

Discussion Questions

- Justice Lewis Powell wrote that “Byron White’s life is the stuff of which legends are made.” What is a legend? Do you think that Byron White was “legendary”? Why or why not?

- Which three character traits best describe Byron? Support your answer with details from the text.

- Chief Justice Rehnquist, who worked with Justice White for 21 years, said that “his judicial work defies easy categorization.” Do you agree or disagree? Explain.

- Why did Byron disagree with the doctrine of substantive due process?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and law professor Dennis Hutchinson for his contributions, review, and feedback.

Greenhouse, Linda. “Byron R. White, Supreme Court Justice for 31 years, dies at 84.” The New York Times. April 15, 2002.

Hutchinson, Dennis J. The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White: A Portrait of Justice Byron R. White. New York: The Free Press, 1998.

Jost, Kenneth. “The Courtship of Byron White.” ABA Journal 79 (1993).

Powell, Lewis F., Rhesa H. Barksdale, David M. Ebel, Lance Liebman & Charles Fried. “A Tribute to Justice Byron R. White.” Harvard Law Review 107, no. 1 (1993).

Rehnquist, William H. “A Tribute to Byron R. White.” Journal of Supreme Court History (1993).

Featured image: Portrait of Byron White. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.